In the seventh episode of the Decolonisation podcast, Taras Kuzio, a renowned British-Canadian political scientist and expert on Ukraine, delves into the challenges of shifting perceptions of Ukraine in Western academia.

In this interview, Dr Kuzio explores how academic biases shape policy decisions on Ukraine, why Russianists dominate in post-Soviet studies, and how Ukrainian scholars can counter these misrepresentations.

You cover many important topics, and it would be interesting to hear why you chose this particular area of expertise. Could you start by sharing some context about your work and what drew you to focus on Russia?

The origins of this can be found in the fact that I grew up in Great Britain, and within the academic world there – as is likely also true in the United States and Germany – the field of Russian, Eurasian, or post-communist studies has always been heavily dominated by experts on Russia. This is the only region in the world where one group of specialists assumes or claims authority over the entire region. For example, if you’re an expert on Brazil, you wouldn’t claim to be an authority on all of Latin America or Central America. But if you’re an expert on Russia, for some reason, you believe you have the right – or the knowledge – to comment on events in Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, or Estonia. This is, in many ways, a legacy of the Soviet Union. Most Russian experts lack real knowledge of other countries in the region, yet they often assume they understand them. They write about these countries, especially now in the context of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Quite a few Russianists still rely almost exclusively on Russian sources when writing about Ukraine. Many don’t even bother visiting Ukrainian websites where materials are readily available in Russian. As a result, you’ll find many books that cite Putin, briefly mention the Ukrainian side, and include impressive data about Ukraine, yet lack any substantial engagement with Ukrainian sources. Meanwhile, Kremlin narratives are consistently used. This is what I call academic Orientalism — viewing Ukraine through Moscow’s lens.

This issue extends to journalism as well. The Soviet-era practice of basing most journalists covering the former Soviet Union in Moscow persists. While they may occasionally visit other countries like Ukraine – perhaps during elections or major events – their perspectives are shaped by the people and narratives they encounter in Moscow.

A stark example of this bias, particularly evident in 2014 but somewhat improved since 2022, is how Western academics framed the war in Ukraine. The majority adopted the Kremlin’s narrative, describing it as a civil war within Ukraine. This interpretation was widely accepted by Western academics and many policymakers, especially in Germany and France, reflecting a deeply rooted Russophilia. It perpetuates the tendency to view Ukraine through Moscow’s lens and reinforces this academic Orientalism. There’s also a fixation on portraying Ukraine as a weak, regionally, and linguistically divided country. Russian nationalists often describe Ukraine as an artificial construct — a fabricated state split between Russian speakers and Ukrainian speakers. This narrative has dominated academic writing, with most articles over the past 30 years focusing on linguistic and regional conflicts in Ukraine. By 2022, many Western academics, think-tank experts, and policymakers — much like Moscow — genuinely believed Ukraine would be easily defeated. While there has been some improvement since the Cold War, this bias persists, especially in historical narratives. Ukraine is often depicted as not real or not fully authentic. This perception is deeply ingrained among many academics, making it difficult for them to explain Ukraine’s resilience and its remarkable resistance. It doesn’t align with their narrative of a weak, divided country.

What would you say is the biggest challenge in your research? And what role do you think academia plays in this era of hybrid warfare? At times, academia can feel quite removed from the daily lives of ordinary people, yet it has a significant influence on media narratives and public opinion. Could you share your thoughts on how this dynamic operates?

Historians, I would say, tend to be much more “ivory tower” academics than political scientists or international affairs scholars, who have to engage with the world as it is today. Historians are generally more in tune with what’s happening. However, they still bring their biases into their work, and one of the main ways this shows is by looking at Ukraine through the lens of Moscow. There’s a strong perception among many academics, particularly historians and some political scientists working on Russia, that Ukraine doesn’t truly belong in Europe — that it should be part of Russia. There are also ideological factors at play. Some academics, such as the British Richard Sakwa (a British political scientist and a former professor at the University of Kent – ed.) and others in the United States, lean so far left that they adopt an anti-American, pro-Russian stance. This is similar to the politics of some far-left politicians in Britain, like the former Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, whose anti-Americanism tends to make them sympathetic to Russia. It’s the same for some academics.

Jeremy Corbyn

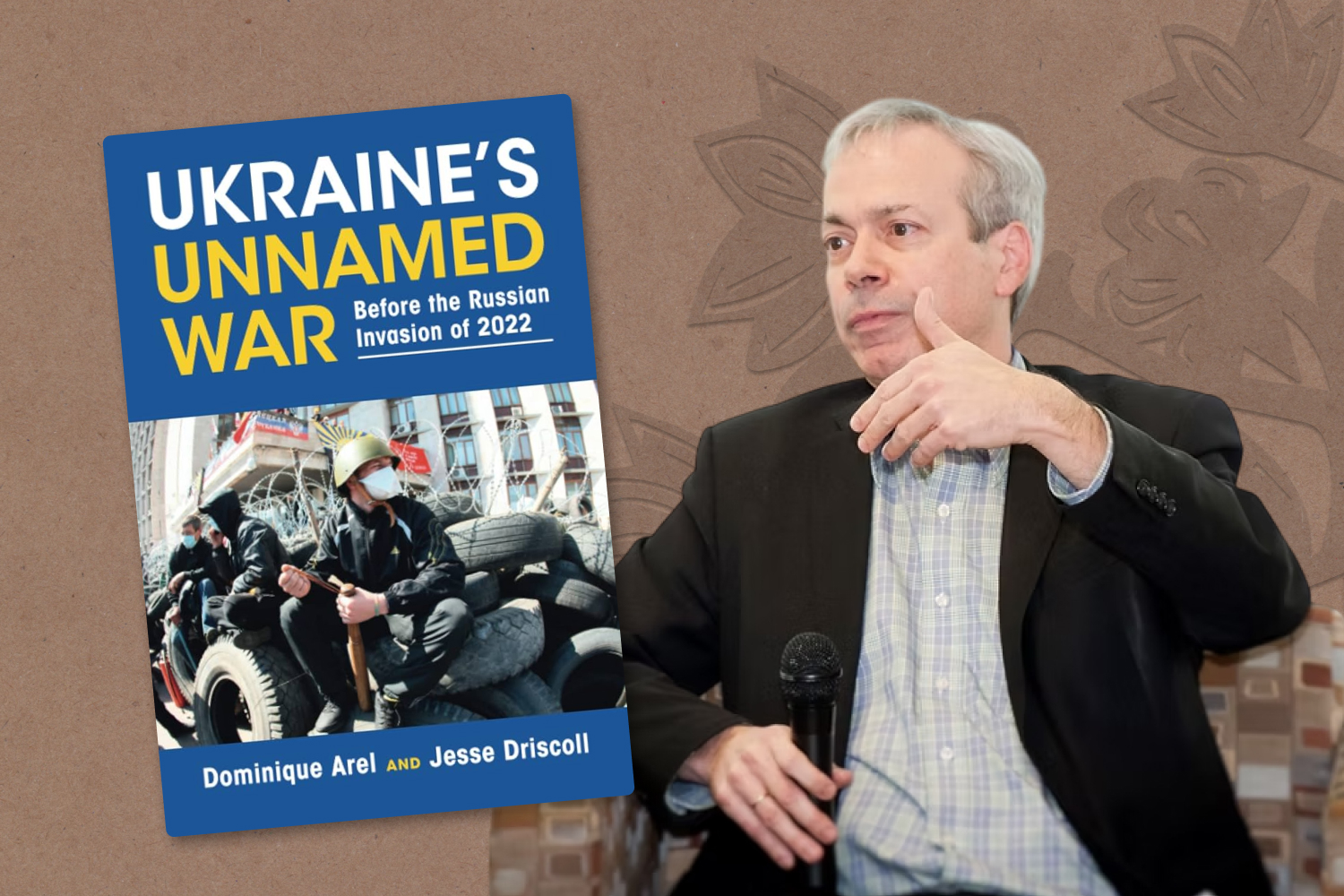

is a British politician who served as the Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition from 2015 to 2020. Corbyn is known for his leftist views, advocating for policies such as the nationalisation of key industries, investment in public services, wealth redistribution, and opposition to austerity measures.What I find especially concerning is their selective use of sources. It’s almost as if they write the conclusion first and then gather the sources that support it. When I review articles for academic journals, I can usually tell when this happens — when the conclusion comes first, and the sources are cherry-picked to fit it. This happens more often than you’d think. A good example is a book by Jesse Driscoll and Dominique Arel, which describes the conflict in Ukraine after 2014 as a civil war. What’s surprising about this is that it was published in 2023, long after the full-scale invasion began. Even more surprising is that Dominique Arel, who chairs Ukrainian Studies in Ottawa, has been writing about Ukraine for years. Yet, he’s been exaggerating the language issue in Ukraine for 30 years, partly due to his own background in Quebec, which shapes his approach.

Today, just as in 2014 but especially since 2022, everyone seems to want to become an expert on this war — whether through social media, books, or other platforms. Many books are being published, but probably three-quarters of them don’t add anything new to the field. People just want to jump on the topic because it brings grants and publicity. However, many of these publications don’t use Ukrainian sources. Sadly, many academics don’t do the fieldwork or use Ukrainian sources, and as a result, they live in an echo chamber. Unfortunately, they continue to influence public discourse because they’re often invited to write op-eds or appear on TV and radio. One example in Britain is Mark Galeotti (a British political scientist, one of the UK’s leading experts on Russia – ed.). While he’s anti-Putin, his writings are so pro-Russian that they end up undermining the Ukrainian perspective; I would call this “soft Putinism”.

I also think part of the problem lies with the Ukrainian diaspora. In North America, where many of the academic centres are, the focus remains on historical events like the Holodomor and Ukraine’s past. There’s little research or publication on the contemporary period – we’re not even attempting to challenge these Russianist narratives.

In your book Crisis in Russian Studies?, which you published before the full-scale war, you analyse academic work on the Euromaidan revolution, the war in Ukraine’s east, and the occupation of Crimea. You point out that some of these so-called pro-Russian or softly pro-Putin academics sometimes use non-existent sources or rely solely on Russian ones. While I understand they’re entitled to their opinions, how is it that such work — especially when it’s supposed to undergo peer review — ends up being published, despite its obvious shortcomings?

The Revolution of Dignity (Euromaidan)

was a series of nationwide Ukrainian protests from late 2013 to early 2014, sparked by the suspension of an EU association agreement. The protests resulted in the ousting of Ukraine's pro-Russian President Yanukovych and the subsequent Russian invasion of Ukraine.Partly, it’s the selective use of sources. For example, there’s simply no excuse for not having abundant sources when writing about Ukraine today. Ukraine has excellent sociological structures, and I know at least four or five that produce outstanding surveys. Yet, Western academics often ignore these, even though they’re all available online. I think the peer review process is very poorly organised. There are quite a few journals today — I’ve experienced this myself — where, when you submit your draft article, you’re asked to go through several journals. The journal often asks authors to specify particular reviewers they would like to look at their work, as well as those they’d prefer to avoid. This practice undermines the review process by essentially creating an echo chamber, where the author is effectively selecting reviewers who share similar views, such as pro-Russian authors or others in agreement. This is also true for book publishers. Hence, I believe this issue with peer review is fundamentally flawed across the academic world, allowing these publications to be released because they’ve been reviewed in an echo chamber.

I encountered a situation where we had to refuse collaboration with someone who worked with Samuel Charap, a senior researcher at one of the most influential think tanks, RAND. While he’s not openly pro-Putin, he subtly shares Russian narratives, and in doing so, he was wrong on every issue. You can’t limit his freedom of speech when he expresses his views, but RAND works directly with policymakers, influencing their decisions and sharing its research. How can we effectively counter this kind of research?

he issue with people like Charap runs deeper, and it’s not just him. A paper recently published on the website of the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank analyses how American think tank experts and academics completely misjudged the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Samuel Charap got everything wrong. What’s surprising is not his views, which can be whatever they want, but the fact that the RAND Corporation continues to employ people who consistently make such errors, and Charap is one of them. But it’s not just Charap. The most frequently invited person on podcasts discussing the Ukraine-Russia war is Michael Kofman (one of the leading US experts on Russian military affairs and national security – ed.). He also got everything wrong before the full-scale invasion. In Washington, there’s a term for people like them: “Beltway bandits”, named after the Beltway, the ring road around the capital. These bandits are constantly seeking grants from the US government, like the RAND Corporation. But they all got it wrong because they bought into the myth that the Russian army was the second-best in the world. Michael Kofman published an article in Foreign Affairs just three days before the full-scale invasion, suggesting that the Russians would simply walk in and quickly defeat Ukraine. Yet he remains a frequent guest on podcasts, despite his mistakes. They all got it wrong because they believed the hype about the Russian military. What surprises me the most is this: if Russia is indeed a mafia state as U.S. diplomatic cables have been saying since 2010 – there’s a WikiLeaks cable from Madrid, 2010, describing Russia as a mafia state – then everything in Russia is corrupt, including the military. Why didn’t these experts recognise this? It means this is not the second-best army in the world; it’s barely the second-best army in Ukraine.

The RAND Corporation

is an American global policy think tank founded in 1948. Originally focused on providing research for the US Armed Forces, Since the 1950s, RAND research has played a crucial role in shaping United States policy decisions on a broad range of key issues, including the Cold War.The Cablegate

was a massive leak of U.S. diplomatic cables by WikiLeaks in 2010, consisting of over 250,000 classified documents from 274 U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide. The leak exposed sensitive information on a wide range of issues.However, people like Charap are more dangerous than Kofman. At least Kofman has become pro-Ukrainian since the full-scale invasion. Charap, on the other hand, adopts an arrogant form of realism, as if Ukraine doesn’t matter. He would back whatever Putin desires. And what does Putin want? Putin is aiming for a second Yalta — a summit with Trump to divide spheres of influence between the U.S. and Russia, much like they did in 1945. Charap is fine with that and doesn’t care about the opinions of Ukrainians. Lastly, American academics and think tankers fail to understand nationalism, perhaps something we better understand in Europe. These so-called experts never saw the rise of Donald Trump or populist nationalism in the U.S. In a recent book — published by the RAND Corporation just months before the full-scale invasion, with Charap at the helm — they claimed that ideology and nationalism were not driving factors for the Russian military or foreign policy. This was completely wrong, but these are the ideas they’ve been feeding to the Pentagon, given the substantial funding RAND receives from the Department of Defense.

Then there’s John Mearsheimer — he’s fixated on Ukraine and also a notorious antisemite, which is telling. What’s particularly interesting is that he openly admitted to receiving money from the Kremlin-linked Valdai Discussion Club to publish his books. It’s not always easy to trace whether these so-called experts are directly funded by Russian money, but what’s your take on this? Do you think it’s more about Russia manipulating “useful idiots”, or is it part of a more organised effort to influence Western academia through grants, clubs, and media?

The Valdai Discussion Club

is a Russian think tank and discussion forum founded in 2004 to facilitate dialogue between Russian and foreign experts and policymakers on global issues, and is widely criticised as a Kremlin tool to influence the global perception of Russia.

Russian money has been flowing into the West for a long time, and often, it’s impossible to trace. However, I think you can generally distinguish between useful idiots and paid agents. I wouldn’t put Mearsheimer (an American international relations expert known for his criticism of Ukraine’s EU and NATO alignment, claiming it sparked Russia’s invasion – ed.) in the same category as Sakwa. Mearsheimer is right-wing, so he’s more aligned with the realist school, like Charap. Anatol Lieven, the Quincy Institute in Washington, and Sakwa represent that extreme left, anti-American, pro-Russian tendency. Mearsheimer and Charap, on the other hand, tend more to this realist approach.

Today, it’s harder for these people than it was in 2014. Russophiles have to be more careful now because Russia is committing massive war crimes. The Ukrainian Prosecutor’s Office has documented 140,000 cases of war crimes. If you’re a Russophile today, you have to camouflage your stance in ways you didn’t have to back in 2014. Now, they say things like, “I want peace” or “I hate bloodshed”, but by “peace”, they really mean Ukraine should compromise. Not Russia – Ukraine; Kyiv should give up territory, give up people, and essentially admit defeat. It’s how they disguise their pro-Russian stance today.

Realist theory

is a framework in international relations that asserts states act in their self-interest to ensure security and power, with conflict being an inevitable outcome in this anarchic international system.I think Charap’s influence has probably impacted the Biden administration. There’s evidence that he’s been invited to speak to people within the administration. My main criticism of the Biden administration is their drip-drip supply of weapons to Ukraine. They’re guilty of allowing the war in Ukraine to become a forever war. This war could have ended in 2023. But the Biden administration was so afraid of Russian nuclear weapons, escalation, or Russia collapsing in a way similar to the Soviet Union in 1991, that they hesitated to give Ukraine all the weapons it needed right away. Instead, they kept supplying them gradually over a long period. This approach led to the failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive in June 2023. That kind of obsession with what Russia thinks — what Russia might do, whether Russia might use nuclear weapons — has caused the Biden administration to miss the opportunity in late 2022 when Ukraine could have defeated Russia. At that point, there were only 170,000 Russian troops in Ukraine, no fortifications, and those so-called “Surovikin Lines” (defensive fortifications Russia built in occupied areas to prevent Ukraine from reclaiming them – ed.) hadn’t been built yet. Ukraine had just completely defeated Russian forces in Kharkiv and was about to do the same in Kherson. If, in September, October, or November of 2022, the United States had given Ukraine everything — missiles, tanks, jets — Ukrainian forces would have reached the Black Sea coast and defeated those Russian forces. But the administration’s paranoia about escalation, fueled by people like Mearsheimer and Charap, prevented this.

This connection between Russian-centered academia and its influence doesn’t just affect the realm of ideas; it directly impacts what happens on the frontlines. That’s why I’ve consistently vastly underestimated hybrid warfare in the West. For far too long, it’s been dismissed. Do you think it’s possible to realise that academia is part of this hybrid warfare?

Certainly, what we are experiencing now is that everything Russia is doing in this war is now weaponised. And Russia is doing that in the West against Western interests. For example, Russia strongly influences the Russian diaspora in the United States. The FBI has even investigated the Russian diaspora in the United States because of many agents that came out. You know, nearly a million Russians fled Russia after the mobilisation in September–October 2022, and apparently, a lot of those are now agents in the West. So, Russia has weaponised many different components of life in the West, which inevitably impacts academic work, think tanks, and such. Many institutions are now more cautious about taking money from Russia; that’s become more taboo. Academic exchanges have also gone down, but that change came in 2022, not 2014. So, I think Russian academic and think tank worlds are more cut off from the West today, and that’s very good because most Russian academics and think tankers support the genocidal war against Ukraine – this is a fact. Some of them continue to publish in the West, but people like Karaganov and others like him are just mouthpieces for the Kremlin today. Russian academics are not rebelling against the war on Ukraine — they’re supporting it — and we in the West should understand that. I think it’s impossible to change the minds of people like Lieven, Mearsheimer, Charap, and Sakwa. But we have to realise they’re very prolific. Sakwa publishes books every one or two years, and they get through the review process. His first book on the war in Ukraine was published in 2015. I reviewed it, and the only Ukrainian source he used for writing about the war was the Kyiv Post (a Ukrainian English-language media – ed.). Where are the primary sources? There were none. Sadly, this tendency will continue. Today, people like this are more camouflaged, but I don’t think they’re going to change their viewpoints. Change has to happen with the Ukrainian government, embassies abroad, and the Ukrainian diaspora in North America. They need to realise they should be more proactive and attend conferences, challenge these academics, create panels, and write articles for major outlets like Foreign Affairs. And that’s surprising with Zelensky because he’s so good at PR, but I don’t think he and his team understand how the Western world works in terms of influencing policymakers, academics, and think tanks.

Sergey Karaganov

is a Russian political scientist and author of the "Karaganov Doctrine" which advocates for the Kremlin to use the pretext of "defending" ethnic Russians and Russian speakers in the former USSR to gain influence in these regions.Ukraine’s problem is that we do ad hoc solutions for different things, but we don’t have an institutional approach — especially regarding academia or media. But to continue the thought you mentioned about Russian money becoming taboo since 2022 — I spoke at Oxford University this December (2024 – ed.), and students told me Pakistan is financing events where they invite Russian experts. Ukraine’s representation, in comparison, is small.

Right, quite a few countries in London and Washington provide financial grants to think tanks to prepare papers, which is quite common. You can get away with this in the United States because it doesn’t fall under the Foreign Agent Registration Act, which doesn’t apply to think tanks. However, Russia is finding ways around bans by funnelling money through other countries or sources. Where we should talk — and I think this is a more controversial area — is what to do with Russian literature and culture when discussing decolonisation. In Ukraine, since 2022, there’s been a process of de-russification, which didn’t happen after 2014. After 2014, you had de-communisation with the adoption of four laws in 2015 which were strongly condemned by many academics in the West. They claimed it banned the Russian language and persecuted Russian speakers — none of this was true. Opinion polls showed that only 3% of Ukrainians ever saw any issues with the Russian language. But since 2022, the de-russification process has removed statues of figures like Pushkin and Tolstoy. Western academics and Russophiles struggle to see these writers as supporters of Russian imperialism and colonialism. British writers in the 19th century supported British colonialism, while these Russian writers backed Russian imperialism as well. The reason these statues are being removed now and not after 2014 is because Russian military aggression is so severe that even Russians in Odesa (Ukraine’s 3rd-largest city located in the south of the country – ed.) have become anti-Russian. Russia’s aggression, significantly since 2014 and 2022, has fundamentally changed Ukrainians’ attitudes toward Russia. Opinion polls show less than 5% of Ukrainians now have a positive view of Russians. This is why I believe it’s time for Western academic centres to move Ukrainian studies out of Eurasian or post-Soviet departments and into European departments. Ukrainians and Russians are now divided for decades to come.

The Foreign Agents Registration Act

is a U.S. law that requires individuals and entities representing the interests of foreign governments to register with the U.S. Department of Justice, ensuring officials are aware of efforts by foreign actors to influence U.S. policy.

You just mentioned that many British writers in the 19th century supported imperialism. Now, if we talk about Kipling or someone like him, we can still discuss and read him, but we understand the context. So why is it so hard for scholars to accept that Russia is an empire, not a nation-state? Russian studies often treat Russia as just a country, overlooking the fact that Ukraine, Georgia, and other regions were once part of the Russian Empire.

Western academic resistance to this stems from a lack of comparative studies. Too few scholars have compared the Soviet Union or Russia as empires to Western empires. Alexander Motyl (an American historian and political scientist, expert of the USSR and Eastern Europe – ed.) has done this, but it’s rare. And historians of Russia haven’t changed their approach since 1991. They still use 19th-century imperial-nationalist frameworks. The first chapter of Crisis in Russian Studies? surveys these Western histories and examines how they adopt the same basic approach to Russian history as Putin and the Kremlin. This so-called “thousand years of Russian history” narrative — shared by both Western historians and Russian state propaganda — presents a timeline that includes Kyivan Rus, Vladimir-Suzdal (a mediaeval principality in Eastern Europe, predecessor of Russian statehood – ed.), Muscovy, the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and the Russian Federation. Both sides perpetuate this view. This narrative is deeply flawed as it ignores Ukraine, failing to acknowledge that the histories of nations typically focus on the territory that constitutes the country. For example, the history of Britain covers the territory of Britain. Similarly, the history of Ukraine begins with Kyivan Rus, primarily located within contemporary Ukraine. This narrative also disregards Ukraine’s perspective on history, yet Western historians of Russia, like the Kremlin, treat this history as an Eastern Slavic or pan-Russian continuum — essentially a Russian history where Ukrainians are seen as an extension of Russians. This perspective prevents them from recognising Ukrainians and Russians as distinct peoples. This deeply entrenched view in Western histories of Russia has persisted for decades. An example comes from 1992, when then-president of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk visited Germany. He was offered a Russian interpreter and responded that he only spoke Ukrainian.

The German hosts were puzzled, comparing Ukraine to Bavaria within Germany — a mere appendage to Russia. This perception only began to shift after the Orange Revolution and especially after the Euromaidan Revolution and Russia’s military aggression in 2014. The West has taken significant time to see Ukraine as separate from Russia, but Western historians of Russia largely remain unchanged. They continue to promote a pan-Russian or Eastern Slavic framework, where Ukraine is denied an independent identity. Western histories of Russia remain fixated on the Russian Empire. There is still no comprehensive history of the Russian Federation as a nation-state. Instead, Western scholars continue to uphold an imperialist narrative, failing to develop or encourage a post-imperial, civic national identity for Russians. This outdated perspective has real-world implications. For instance, when Ukraine expressed a desire to join the EU, the response was often that inviting Ukraine would necessitate inviting Russia. This view that Ukraine’s aspirations were inherently tied to Russia only started to change post-2014. What has most surprised Western academics, policymakers, and think tanks in recent years is Ukraine’s resilience. While Ukrainians and many familiar with the region were not surprised, the West had expected Ukraine to fall quickly under Russian aggression. Instead, Ukraine has withstood relentless military pressure and war crimes for years. This resilience has forced a reevaluation of Ukraine’s role and identity, though many in the West struggle to accept this shift fully. This view, which romanticises the Russian people and dissidents, remains pervasive among some Western experts like Mark Galeotti and Maximilian Hess (a British political economist and expert on Russian and Eurasian affairs – ed.), who argue that this is Putin’s war, not Russia’s.

The Orange Revolution

was a series of nationwide protests against electoral fraud favouring the Russian-backed candidate Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine's 2004 elections. The rallies led to a re-run, resulting in the victory of pro-EU Viktor Yushchenko and broad democratic reforms.

I don’t think they fully grasp the consequences. Almenda, a Ukrainian human rights group, reported that Russian universities are involved in indoctrinating abducted Ukrainian children. These institutions are effectively brainwashing them, yet many still collaborate with Western universities, sending students and professors — who are part of this — to the West for degrees and work. Italy, for example, has been a leader in this, while Germany has been more proactive in halting it. Italy and France, however, were more reluctant to change. The U.S. seems uninterested, but Europe appears more receptive.

Well, I’m not surprised by Germany and France. In Europe, these two countries have always been the most Russophile, especially in academia – particularly Germany. The “Putin understander” concept came from Germany, and Ukrainian studies were always weak there and in France, dominated by Russophiles. In Germany, some of these figures and children of Russian émigrés were very influential, like [Alexander] Rahr (a German political scientist and expert on Russia, advocating for stronger ties between Germany and Russia – ed.). They promoted the long-standing belief that Germany and Russia should work together, which was dominant before 2022. They thought Germany could influence Russian domestic policies through trade, which, of course, was wrong. They even continued to support Nord Stream 2 after 2014.

Nord Stream 2

is a natural gas pipeline running from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea. Completed in 2021, it was criticized for increasing Europe's dependence on Russian energy and bypassing Ukraine’s as a traditional transit country, giving Russia greater geopolitical leverage on Europe.Let’s remember, in 2014, the West betrayed Ukraine. It wasn’t just academics and policymakers — the U.S. under Obama and British Prime Minister Cameron ignored their commitments to Ukraine in the Budapest Memorandum. The sanctions on Russia were minimal, and Western governments kept business as usual with Russia. They also adopted the view that the conflict in Ukraine was a civil war, with Russia not really involved. This weak stance sent a damaging message to Russia. One of the reasons Russia miscalculated the 2022 invasion was due to two wrong assumptions: that Ukrainians were “little Russians” waiting to be liberated and that the West would respond weakly, as it had in 2014. Both were wrong, but the weak response from 2014 to 2021 fueled the misjudgment, with Germany and France central to that weakness, especially in the Normandy Format (a diplomatic group of Ukraine, Russia, Germany, and France established to address Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine – ed.) talks

We haven’t touched on Crimea, though. In 2014, it was shocking how many Westerners, including academics, dismissed Ukraine’s position, saying, “Crimea was always Russian.” This view deeply shaped Western policymaking. Poroshenko (Ukraine’s president in 2014-2019 – ed.) often said that Western leaders told him to forget about Crimea, claiming Ukraine had lost it forever. This view ignored Crimea’s true history: it wasn’t part of Russia until 1783 – for over 600 years, it was ruled by the Crimean Tatar Khanate. Erasing the Crimean Tatar identity is a racist approach to the region’s history. Western policymakers let these biases shape their attitudes, with Germany and France playing key roles. While Germany has shifted since 2022, Timothy Snyder points out that Germany often overlooks countries like Ukraine and Poland in favour of its relationship with Russia, a deeply concerning issue. Many fear that once the war ends, leaders like Olaf Scholz may push to return to “business as usual” with Russia.

This hypocrisy in liberal democracies is staggering. Countries that champion minority rights often ignore groups like the Crimean Tatars. Since 2014, Russia’s treatment of them has been genocidal — imprisonments, cultural erasure, and repression akin to Stalinism. Yet, Crimean Tatars rarely get representation in Western think tanks or academia. A notable exception is Professor Robert Magocsi in Toronto, who wrote a book on the plight of Crimean Tatars in 2014. But such voices are rare. This neglect is especially hypocritical given the West’s supposed commitment to multiculturalism and minority rights. Some of it may stem from Islamophobia, which also affects attitudes toward Turkey, a strong supporter of the Crimean Tatars. Turkey has long supported Crimea as part of Ukraine, but strained relations with the West may be sidelining the issue. It’s surprising, given Turkey’s role in weakening Russia’s position in Syria – something Obama failed to do.

We talked about this on the podcast — how Ukraine and the region more broadly, including the Crimean Tatars, can be integrated into wider academic disciplines. Not just as a standalone field of “Ukrainian studies”, but as a lens to explore broader topics like European history and imperialism through the Ukrainian perspective. Are we at a point where this kind of integration is happening, or is it still too soon for academia to make that shift?

I think one of the things Western academics working in the field of Eastern European, Russian, post-Soviet, or whatever you want to call it, Eurasian studies, have to accept now is that the break between Ukraine and Russia has become a gulf. Relations will never be the same between these two nations and countries again. They also have to accept that the national identity of Ukrainians has changed radically since 2014, and especially since 2022. The de-Russification and movement away from the Russian language and Russian history — all of this is now happening at a rapid pace in Ukraine. This means there needs to be a rethinking of where Ukrainian studies should be placed. Ukrainian studies, both historical and contemporary, should no longer be housed in departments dealing with Russia, Eurasia, or the former Soviet Union. It’s time for Ukrainian studies to be moved to European or East European studies, whichever you prefer. That, I think, would represent a fundamental psychological break. It would be very important to place Ukraine outside of Eurasia, the post-Soviet world, and the Russian world.

Most Ukrainians now — the majority — support EU and NATO membership. Less than 5% of Ukrainians support any integration into Eurasia. Ukraine has a clear path to join the European Union — maybe one day NATO, but certainly the European Union for now. I think Western academia needs to catch up with both Ukraine’s national identity and its alignment with the European Union, and accept that Ukraine is a European country. It’s no longer post-Soviet, Eurasian, semi-Russian, or whatever you want to call it — those days are gone. That would be a major demonstration of how academia and think tanks have come to understand the revolutionary changes taking place in Ukraine.

If one follows the opinion polls, as I do, the changes in Ukraine are revolutionary and irreversible. You cannot go back from this. So, it’s time for academic centres to accept this. I don’t think many of these Russian specialists find it easy to do so, because they continue to see this region — this former Soviet space — as one entity. But that is no longer true. Countries like Central Asia are moving towards Chinese influence. The South Caucasus is a mixed area; Azerbaijan has moved away from Eurasia. Ukraine and Moldova have both moved into Europe. The three Baltic states made their move long ago. It’s time to stop considering this former Soviet space as a single entity. It no longer exists. I think this would probably be one of the best outcomes of this full-scale invasion and war. It would also show Ukrainians that we now see them as Europeans — not as some kind of post-Soviet nation.