In this interview with Dutch author Lisa Weeda, she shares the story of her family and her connection to Ukraine. The interview was conducted by Local History magazine and translated by the Ukraїner International team.

Written by

Solomiia Skvortsova, researcher of the Ukrainian diaspora in the NetherlandsLisa Weeda is a writer and curator of literary programs and art projects of Dutch-Ukrainian origin. Her grandmother, Oleksandra, originally from the village of Blahovishchenka in Luhansk Oblast, was deported by the Nazis as an Ostarbeiter to the Griesheim am Main factory in the west of Germany during the Second World War. After the war, Lisa’s grandmother married a Dutchman and moved to his homeland.

In 2021, Lisa debuted with her novel Oleksandra, named after her grandmother. Through family history, the author immerses Western readers in the tragic events of Ukrainian history: the Holodomor (a man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine that killed millions of Ukrainians – ed.), Soviet collectivisation, and the war raging in the east of Ukraine since 2014.

In July 2024, Lisa’s grandmother, Oleksandra, passed away peacefully. Her family was by her side.

Ostarbeiter

The term Ostarbeiter literally translates into “Eastern worker”. It was used to refer to people deported from Soviet-controlled territories by the Nazis for forced labour.— You are often regarded as a Dutch-Ukrainian writer, and in your works, you touch on the Ukrainian theme. What brought you to explore your Ukrainian roots?

— In 2013, when I was 23, I learned that my grandma was an Ostarbeiter. Although her relatives would often come to visit us, and I knew she was from Ukraine, this was the first time I began to grasp my family history.

As a child, I had a profound interest in the history of the Second World War and the Holocaust, and my parents and I visited Auschwitz and Buchenwald. However, I had never heard anything of the Ostarbeiters, and when I started researching my grandma’s story, I found that there was almost no information available. I thought people should know more about the over a million girls and women who were forcibly taken to Germany by the Nazis. I went to Germany to see the factory where she was a slave worker, and sent some photos to my mother. My mother showed those images to my grandma, and she confirmed that she had been there.

Lisa Weeda

I felt I needed to fill this history gap, so I started writing my first novel, Oleksandra. It took me eight years to finish it. My family was dispossessed and experienced the Holodomor, and when the war in the east of Ukraine began in 2014, I suddenly discovered multiple parallels.

— What struck you the most while researching your family history?

— The forced collectivisation and dekulakisation in Donechchyna in the 1920s and 1930s, which affected my family severely, were a huge shock to me. In the spring of 2015, as I was researching my family, my uncle was kidnapped in Donechchyna and was found murdered three months later, showing signs of torture. That was when I first realised that history was repeating itself on the same land. I began comprehending why my Ukrainian family would constantly bring me patriotic gifts like a Ukrainian flag or a blue-and-yellow bracelet. In the Netherlands, nationalism is linked with right-wing views and has a completely different function, so it took me some time to identify this difference.

Dekulakization

was a Soviet campaign in the late 1920s and 1930s to eliminate wealthier peasants, known as "kulaks", as a class. It involved mass arrests, deportations, confiscation of property, and executions, aimed at enforcing collectivisation and breaking resistance to Soviet control in rural areas.

Grandma Oleksandra (in the middle) with her friends, 1939

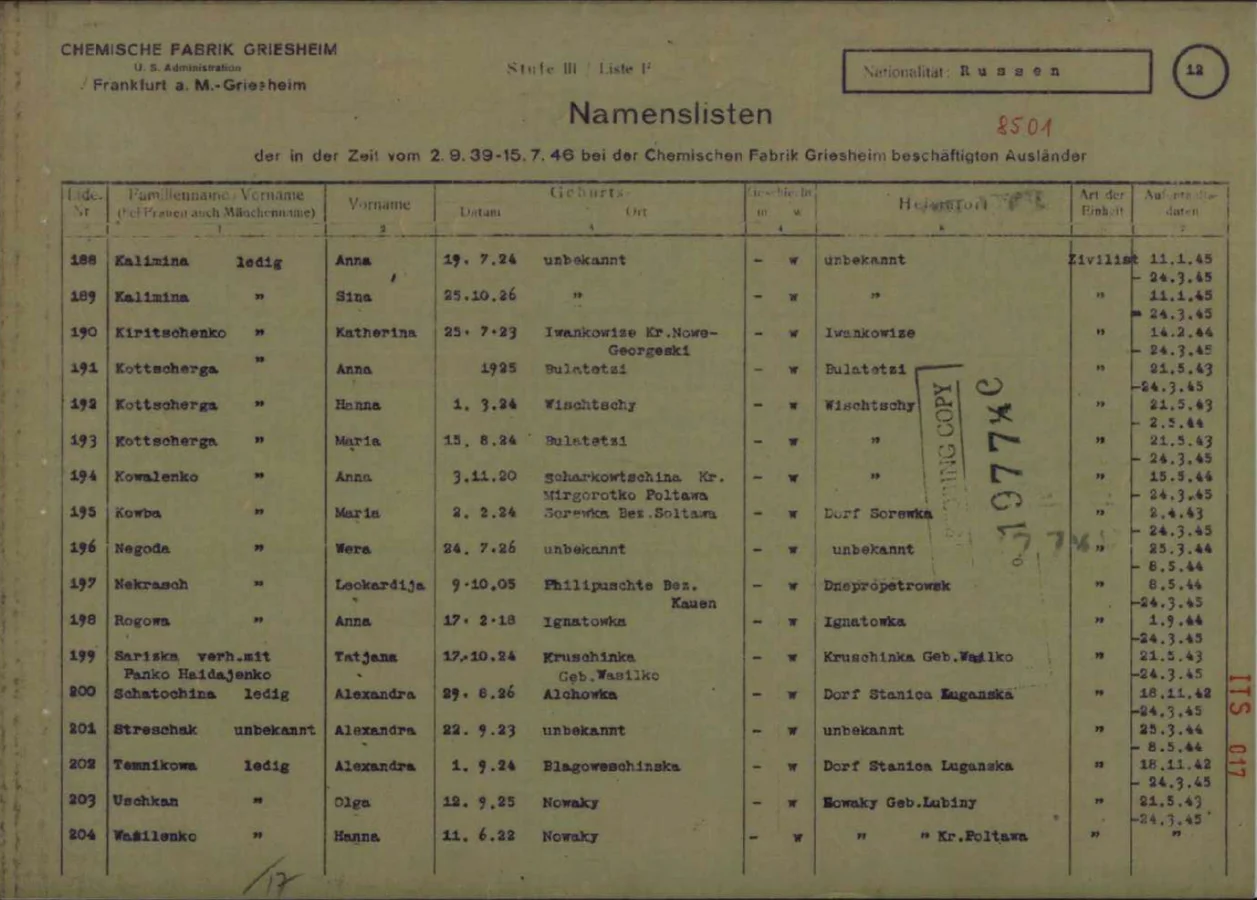

I was also stunned by my grandma’s deportation documents. She was deported on 18 November 1942. It felt so weird to see my grandmother’s first and last names without a patronymic middle name, printed in Latin letters on a piece of paper. I believe it is crucial to have all this physical evidence of her story, since a great deal of Ukrainian history has only been preserved in oral tradition. For example, the evidence of the Holodomor was basically destroyed. Over the eight years of research, I have discovered quite a lot, but the biggest and most distressing revelation happened to me as I realised how scarce the information on Ukraine was in the Netherlands back then.

— How did your sense of self and your family history change once you began writing the novel?

— I was eager to deliver the perspective of East and West to the readers. Clearly, I will never be Ukrainian. I will forever stay more Dutch, but exactly this encourages me to write more about Ukraine. I believe I can be a mediator between East and West, and I deem my works more European than specifically Dutch or Ukrainian. I even considered acquiring my grandma’s name as my middle name: Lisa Oleksandrivna Weeda. Nevertheless, later, I decided that it might be too dramatic.

Documents from the Griesheim-am-Main factory list Liza’s grandmother, Oleksandra Temnikova, under number 202.

— Your novel Oleksandra, published in 2021, has been translated into eight languages, but Ukrainian isn’t one among them.

— I would really love for this book to be published in Ukrainian. I want to connect with Ukrainian readers because I’m not the kind of author who simply presents her work without engaging with the audience. I truly enjoy open conversations with people who can offer me a different perspective.

— Over the past few years, you have travelled to Ukraine many times before and after the Russian full-scale invasion. What were your impressions during your visits?

— In 2018, in Kyiv, I met a group of young politicians, artists, and photographers, one of whom held a high position in a Ukrainian ministry. Later, they came to the Netherlands, where we met in a books-and-coffee place. We’ve been discussing politics for about an hour and a half. After they left, the bookstore manager, whom I knew well, asked me what made us go after politics for so long. He was extremely confused and even a little irritated.

For me, discussing politics is completely appropriate. I have been keen on how politics and power dynamics function since childhood. I admire the fact that in Ukrainian culture, these topics are discussed publicly. In the Netherlands, it works differently. I guess that in Ukraine, people raise political issues more freely because they know what will happen if they don’t follow events. This awareness has entered Ukrainian culture for historical reasons. My family history also made me reflect on this more. I also adore Ukrainian culture and food, as well as the beautiful colours of the buildings, especially in Kharkiv and Lviv. They often come to my mind.

— In the school classes, what were you taught about Ukraine?

— Ukraine was never part of our history lessons at school. From a young age, kids are left with major gaps in their understanding of certain things — and it was the same with the topic of Ostarbeiters. In the Netherlands, there are so-called Slavic studies, but for a long time, they were centred around Russia. My father holds a PhD in Slavic studies, and I remember that, growing up, every book in our house was either Dostoevsky or Tolstoy. People were fascinated by the idea of the “Russian soul”. It’s strange, really. I’m actually thinking of writing my next book about this. As a writer, I feel there’s a lot of work to be done in telling these stories to the audience.

Grandma Oleksandra, 1940s

Lisa with her grandmother, Oleksandra. Photo by lisa_weeda via Instagram

— What was the perception of Ukraine in the Netherlands before 2022, and how did it evolve after the Russian full-scale invasion?

— Until 2022, many Dutch people were unaware of the most basic concepts about Ukraine. Sometimes I had to show Ukraine on the map and explain that it is the largest country in Europe. I suppose most of them have heard about Kyiv in one way or another, but they mostly associate it with the Russian language and culture.

Even now, when I give interviews about my books, it seems that people still associate Ukraine, Sakartvelo (Georgia), and Moldova with Russia.

Recently, a children’s book publisher in the Netherlands approached me about writing a book on Ukraine for kids. The book is meant to go beyond the war and show the country’s rich culture and history. Honestly, I’m quite nervous about it. I want to tell the story in the form of a letter — as if the reader is receiving a message from a Ukrainian child, sharing what their country and culture are really like.

— In your interviews and social media posts, you constantly remind people about Ukraine and the ongoing war. How has the public attitude towards the Russian-Ukrainian war in the Netherlands changed over the past two years?

I can sense a kind of war fatigue in the West — and that’s something I explore in my new book as well. I’m trying to physically transport readers to a different place, one where war is happening, and help them find a way to respond. At one point, the war in Ukraine started to look almost cinematic — unreal — while I knew that real combat was taking place. I found myself drawn to those polished, cinematic videos from United24(Ukraine’s official fundraising platform, launched by President Zelenskyy in May 2022 – ed.) and the Ukrainian government, even though I knew they didn’t reflect the whole reality.

I even read an article by a Dutch author where he compared these videos to watching a movie. It sounds like the world requires constant marketing gimmicks to stay involved and entertained. That scares me because it means we’ve started merely consuming this type of content, and therefore consuming war.

It’s like a fourth wall in the theatre that we cannot break anymore. It’s too dangerous because then people stop engaging and become mere spectators.