Due to the full-scale war, Ukrainian museums with priceless exhibits were threatened with destruction. Some of them are under occupation and have already been looted by the Russians; some have suffered from shelling, and museum workers are forced to leave their hometowns, which is why not everyone manages to stay in the profession. Those who are far from hostilities managed to evacuate or hide all or at least part of the museum fund but work with reduced funding.

In the summer of 2023, the Ukraïner team went on an expedition to investigate culture during war: how wartime realities change it, how it reflects new circumstances, and whether it manages to remain the heart of society, as before. This is how the documentary project Culture during the War began: a series of videos and long-form articles from different regions of Ukraine: West, East, North, South, and Center.

The first series centres on the West and consists of two parts. The first one is dedicated to Andriy Lyubka, the writer and translator from Uzhgorod, who has become a volunteer raising funds for vehicles for the Armed Forces. This article is about two most notable museums in the West of Ukraine: Korsaks’ Museum of Modern Ukrainian Art in Lutsk and Territory of Terror, Lviv Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes.

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, both have become spaces where artists, together with visitors, can rethink the ongoing events, seeking solace and support in art.

Korsaks’ Museum in Lutsk

The city of Lutsk, in Volyn, is famous, above all, thanks to Lubart Castle. However, since 2018, tourists have been coming to Lutsk to visit Korsaks’ Museum of Ukrainian Modern Art. It houses both a permanent art-memorial exhibition of Mykola Kumanovskyi and a rotating exhibition. The museum also hosts a library of art literature, two conference halls, and a gallery of street art called PolychromA (in 2016, the team of the Art-kafedra galley, the original organizers of the museum, organized an eponymous festival of modern urban art).

Mykola Kumanovskyi

An artist from Ukraine, originally hailing from the village of Sataniv in Podillia, has been residing and working in Lutsk since the 1970s. His creative studio has become a significant cultural and artistic hub in the city. He was involved in easel painting, graphics, sculpture, illustrated printed publications, theater performance design, and the organization of art exhibitions featuring innovative ideas for his time.With the beginning of the full-scale invasion in 2022, most of the collection was moved to a safe location, but the museum continues to operate and bring modern art to the people by regularly arranging various exhibitions of Ukrainian artists.

The museum was founded by the surgeon and businessman Viktor Korsak. When he defended his PhD thesis in 1997, a surgeon’s salary was four dollars per month. To support his two children, Viktor initially worked as a porter at night while practicing surgery during the day. Eventually, he decided to venture into business.

The work of Lutsk artist Mykola Kumanovskyi was hanging in Viktor’s office, and a friend noticed it, saying that he would like it for himself. Viktor got to know the artist and bought not just one, but several works from him. First, they hung in his home, but later he opened an exhibition at his Adrenaline City shopping and entertainment complex. This initiative eventually evolved into the modern art museum that bears his family name. It appears that Viktor Korsak’s friendship with Mykola Kumanovskyi inspired him to create a gallery of contemporary Ukrainian art. The collection of Kumanovskyi’s works became the foundation and the beginning of Lutsk’s first private art collection. Today, Viktor serves as both the museum’s founder and its driving force.

— Our museum’s mission is to reflect on the past, change the present, and create the future. The main goal is for a person to enter the museum and leave somewhat changed. The museum operates based on three core principles”: Concept, Collaboration, and Communication.

Pavlo Kovach

A Ukrainian artist hailing from Uzhhorod. His talents encompass painting, graphic art, performance art, and restoration work. He is a member of the Poptrans art group, a co-founder of the Corridor Gallery, and holds membership in the Union of Artists of Ukraine.On the evening of February 23, 2022, the museum opened the exhibition The Wall by Pavlo Kovach. On the third day of the full-scale war, he began to disseminate first aid to the residents of Lutsk. His supermarket chain collected 30,000 food kits, and his hotel chain provided shelter for those fleeing the war, including ten artists.

Meanwhile, his wife and daughter-in-law packed the museum’s collection, though not in its entirety:

— Art is a form of communication with the viewer. That is why I have paintings in offices, clinics and hotels. People have to be able to see it, that’s the only way it affects people. A jug that is in storage is just a jug, but if it enters the context of an exhibition hall it is a work of art, an exhibit.

slideshow

Since November 2022, the museum has been working on a huge project called Cosmogony. The concept is to paint a picture with an area of two thousand square meters, making it the largest in the world. Its creation will also set a record for the longest time to paint a work. The artist behind this project is Petro Antyp, hailing from Horlivka in the Donetsk region. Also part of the project are thematic exhibitions of Ukrainian artists, and 500 applicants have already submitted their works to a panel of experts. They plan to create pictures with the help of artificial intelligence. Viktor mentions that if the Guinness Book of Records shows interest in the museum’s painting, he welcomes it as it would provide valuable publicity for Ukraine.

— You can hold a hundred exhibitions in small galleries around the world, and this will absolutely not affect the image of Ukraine as a country of real high-quality modern art. And you can make one such project, and the world will talk about it. We plan to do so. We should enter world art not to be pitied, but to show something that no one in the world has done. When [Volodymyr] Klytschko became the [world] boxing champion, people started talking about Ukraine as a home to Klitschko, not just as the site of the Chornobyl disaster.

Viktor is worried about the image of Ukrainian art now that many artists have left due to the full-scale war and are exhibiting and selling their works abroad. According to him, charity initiatives are often not about the highest quality work. Such works are bought to help Ukraine, but this creates an impression of modern Ukrainian art as mediocre. It is important for artists to remember, Viktor emphasizes, that they are representatives of Ukrainian art abroad, so they bear a certain responsibility for the cultural image of Ukraine.

Viktor himself does not paint pictures, but is an art connoisseur and tries himself in various roles, including curator. He was inspired by the philosophy of the French thinker and writer Michel de Montaigne to create another art project, the exhibition Thoughts and a part of the Cosmogony project. It raises existential questions about life, death, conscience and war. Exhibits are selected for each of Viktor Korsak’s forty thoughts, including paintings and sculptures combined with background music. The artist calls it a kind of pressure of art on a person, when various receptors for the perception of information are activated. When writing a synopsis of thoughts, Victor used a modern way to speed up this process — ChatGPT.

— In Thoughts, people have responded to the tank in the shape of a greenhouse the most: on one side is war, and on the other is living and invincible greenery.

ChatGPT

A chatbot with artificial intelligence that can work with text, program code, formulas, and numbers, and generate anything it is asked to.

Art performs a therapeutic function not only for the one who creates, but also for the one who perceives it. To understand modern art, according to Viktor, aesthetic intelligence is needed. And to develop it – three things: observation, interaction, and your own creativity.

— Sometimes they ask me: “Look at abstract art, what do you see there?”. You don’t need to see anything there! I always ask in response: “When you look at the sunset, what do you see there?”. This is how you should look at abstract art.

Viktor observes that the war has led to the creation of numerous opportunistic works, which cannot truly be called art and are destined to be forgotten, much like what occurred with the Soviet ideological heritage.

Instead, he is certain that Ukraine must reclaim its cultural heritage by ensuring that the works of artists like Kazimir Malevych, Ilya Ripyn (known as Repin), Oleksandr Arkhipenko, and others are recognized as part of our country’s heritage and can be studied here. For centuries, Russia destroyed Ukrainian art or appropriated its achievements. Viktor emphasizes that modern Ukrainian cultural figures need to be bold and assertive because small steps won’t lead us anywhere.

Petro Antyp, the creator of the painting Cosmogony, paints daily, and is involved in sculpture. He believes that self-organization is essential for an artist to accomplish anything. He points out that the phrase “an artist must be hungry” has Russian origins and should be avoided.

— I went to many workshops in Europe, saw how the French and Germans work. Everything is clean and tidy with them, their portfolio shows what they have done, what they are thinking of doing, everything is clear. It’s essential to replace the Russian and Soviet mentality, where art was defined by the tsar, the party, or Putin, while in Europe, what distinguishes an artist is their freedom, and their ideas are unbound.

Petro is sure that artificial intelligence will never surpass a real artist. While some may appreciate “algorithmic” paintings, an artist can synthesize ideas from past and present knowledge, as well as from their unique experiences and worldview.

Petro is interested in the myths of various peoples of the world and interprets them in his works. In the painting Cosmogony, he started with the way the birth of the earth was once described:

— In Egyptian myths, a rabbit killed a snake, and a tree grew. It is in my painting: the Sky is his breath, the Moon is one eye, the Sun is the other.

According to Petro, there is a problem with art education in Ukraine, because most teachers do not focus on the world of the student, but train a craftsman who knows technique but does not know how to express themselves in their work. Above all else, freedom should be paramount for Ukrainian artists.

Petro’s grandfather is an artist, and from a young age the artist loved the smell of paint. He started painting early and received his art education in the Russian city of Penza. He says that at his home, in Horlivka, they spoke a mix of Russian and Ukrainian, while Ukrainian schools were closed. Only in Russia was he told that he was Ukrainian. There, Petro began to unite with other Ukrainians who studied with him. He was preparing to enter the academy in Moscow but he went home after an incident.

— An academic named Chesovitin said to me: “Why do you want to join the Academy? It’s better to go to the Union of Artists and live in Moscow. The most important thing is: do not go to Ukraine, as khokhly (derogatory name for Ukrainians — ed.) have no wings.” This phrase made everything clear to me, so I turned around and went home.

At home, Petro got acquainted with Ukrainian art, the names of masters whom he did not know before, and realized that Ukrainian art is amazing. He began to travel the world, while also working in Horlivka. Russian aggression (in 2014 — ed.) forced him to leave his home, workshop, and business. Although his paintings were rescued, but his sculptures had to be left behind.

Stoic philosophy helped him survive the loss of his home, and he decided to start life with a clean slate. He believes that nothing belongs to a person except his own emotions and thoughts, and they can be controlled.

Stoicism

A philosophical tradition that emerged in ancient Greece in the third century BC. Its main ideas include controlling one's emotions, thinking rationally, accepting necessity and nature, and developing morality.

Currently, in Petro’s opinion, Ukrainian artists face a signidicat challenge. Despite all the military victories, Ukraine cannot truly be recognized as a great power without presenting its culture to the world. Fortunately, there is much to present:

— In our country, every woman who paints eggs for Easter is an artist. We have such embroidery!

Petro notes that there are many grants for Ukrainian artists as refugees but they do not open Ukrainian art to the world, because this can only be done with big, bold projects. And it is better to make two powerful ones than to scatter on thirty.

Artists will continue to reflect on the Russian-Ukrainian war in their works for a long time. Petro hopes they will not only highlight the tragedy but also emphasize heroism.

— The 300 Spartans lost everything, but they are heroes who did a feat. Our Mariupol is also a feat. I want to paint a true, strong Ukraine so that people are proud of it.

Artists cannot be outside of politics. If they are public, they are already a part of politics, even if they do not feel or realize it, Petro believes.

— Wasn’t Taras Shevchenko involved in politics? Ivan Franko as well? And Vasyl Stus? Name me an artist who remained completely apolitical. Read Ripyn’s diaries, what he wrote about Russians.

In galleries, encyclopedias and collections, the nationality of artists is indicated. Petro urges Ukrainians to return the names that were intentionally misappropriated by Russia. Once, he was flipping through a Russian portfolio where a thousand artists were presented, and their nationality was indicated everywhere. However, the thirty Ukrainians who were among them were labeled as Russian or simply “born in Melitopol / Odesa / another city.” It is surprising that this was compiled by professionals.

Ukrainians underestimated themselves for a long time, and Russians took advantage of this. But now Ukrainians are rethinking their culture, studying history and getting to know themselves, so the artist sees a bright future:

— I think that Ukraine will have a great future. Everything is going to be fine with us.

Territory of Terror museum in Lviv

Olha Honchar is the director of the Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes Territory of Terror, located on the site of the former Lviv ghetto, the third largest in the Third Reich, which existed from 1941 to 1943. The museum was opened in 2017 and consists of an exhibition and a space for discussions and presentations. Visitors will see a “cattle carriage” (people were deported in such carriages), reconstructions of a typical Lviv resident’s home in the 1920s and 1930s, bedrooms after a search, arrest or deportation, a camp barracks, and a Soviet archive where there was a case file for every arrested person. One of the parts of the exposition that is constantly replenished is a collection of monumental Soviet art, where decommunized monuments are taken after being removed from public spaces.

— When there are such museums, history does not seem to be black and white, it does not seem to be gray, it is just confusing; however it clearly shows how a person can resist and remain human.

slideshow

From February 24 to September of 2022, the museum was closed to visitors but employees conducted tours about the history of the city for internally displaced persons. Part of the team evacuated abroad, so new staff began working in the museum.

At midnight, before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Olha was brainstorming a potential evacuation with a colleague from the Starobilsk Museum in Slobozhanshchyna. By eight o’clock in the morning of the next day, together with the team of her museum, she was already packing exhibits. Some documents were already digitized, valuables were concealed, and windows were taped shut. They also sought out places that could accommodate displaced people from other cities.

— Since the first days of the war, Lviv became a logistical hub. Everyone I knew from the museum field including international partners called us because we could be reached, as others were either on the road or under fire.

The first weeks of the full-scale war saw the creation of the Museum Crisis Center, an initiative that has been helping museum workers ever since, including financial support during evacuation. More than a hundred museums across ten regions (mostly Donetsk region, Kherson region, Sivershchyna region, and Slobozhanshchyna region) have already been helped.

— Currently, the life of [any] museum in Ukraine depends on its territorial location: the further from Russia, the better. Those located closer to the border are either occupied or destroyed. Farther from the border, events and art therapy are held even in empty premises.

Throughout 2022, the Territory of Terror museum worked to preserve their collection and digitize exhibits. Thanks to the audio guide in Ukrainian and English, you can learn about their museum objects in any corner of the world.

— It is important for us to have a copy of the museum on a flash drive, so that if something happens, there is something to restore.

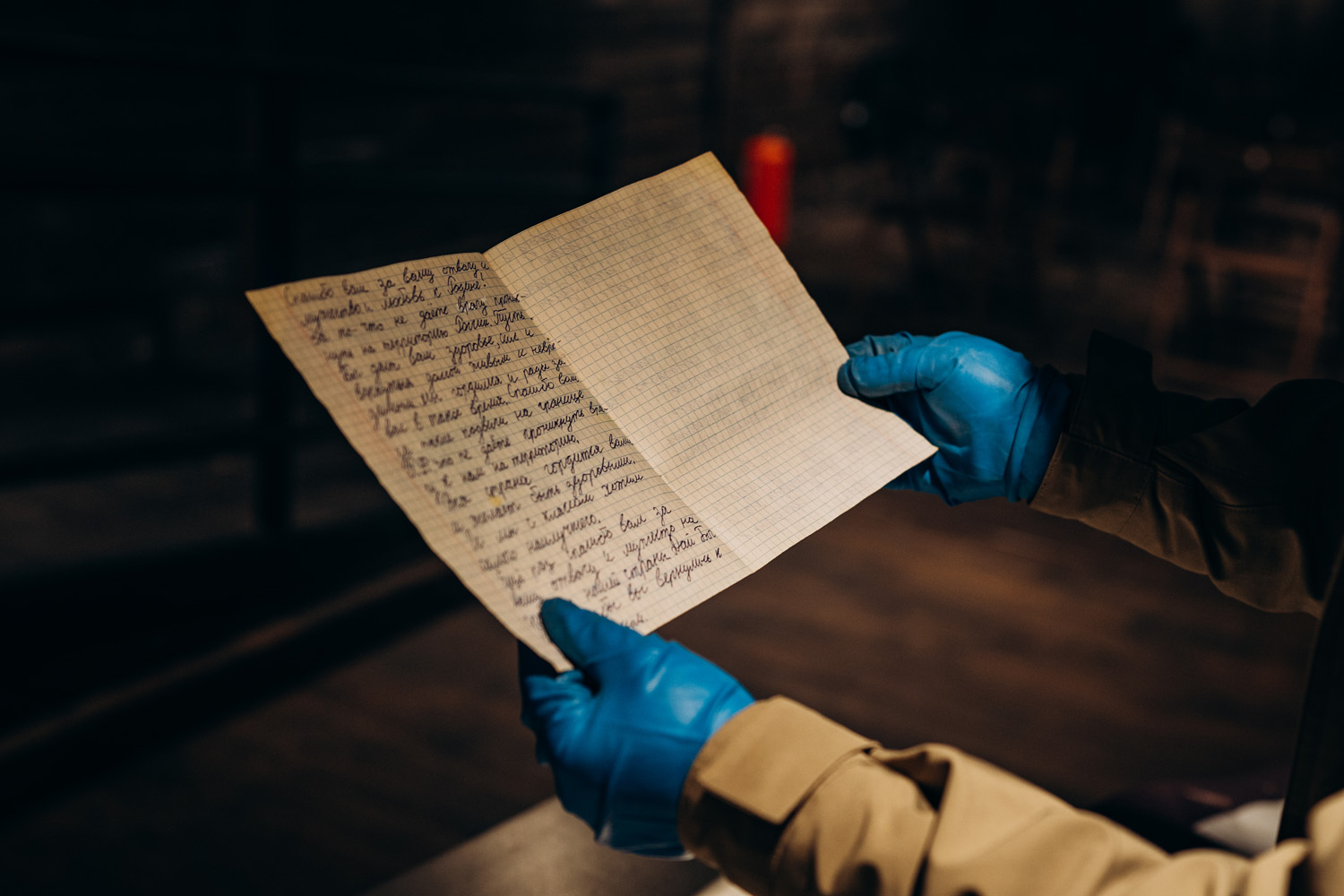

Taras Rizun is the chief custodian of the collection of the Territory of Terror museum. He is responsible for recording and storing the exhibits, as well as scanned data on electronic media.

Taras was directly involved in process of scanning the exhibits. A 3D tour of the museum can be seen on the museum’s website. As of 2023, there are already 50 of the most valuable exhibits available, with brief descriptions. Taras notes that being able to visit the museum from home encourages people to visit it in person.

— Creating a 3D model of a single exhibit requires taking hundreds of pictures from various angles. An example comes to mind: a 3D model of a shirt by Olha Popadyn, which she embroidered while she was in prison on Lontsky Street in the 1950s. This shirt could not be scanned simply by hanging it on a hanger or holding it in your hands. We put it on a mannequin, and the guys with cameras literally danced around it: we filmed from above, from the sides, and from below.

Olha Popadyn

Member of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). She was convicted in the “Trial 59” of 1941. At that time, 59 young Ukrainians, mostly students of Lviv universities, were brought to trial. They were accused of belonging to the OUN, of anti-Soviet activities and of preparing an uprising against the Soviet regime.In times of war the museum cannot function as it did during times of peace. The primary focus of activity shifts to preserving the collection and offering mutual assistance. Taras notes that if the Russians wanted to be honest with themselves, they would have to derive their history from other sources. And as long as they do it on the basis of stolen material, they will want to destroy Ukrainians.

Despite the war, theaters continue to operate, writers are producing books, publishers are releasing them, and artists are creating paintings. Cultural life continues, but institutions are more difficult — they are less nimble than a business or an independent artist. They rely on funding and require state protection, which is currently primarily focused on the war effort.

— On the banner of the Kholodnyi Yar rebels was written “Freedom or Death.” We have a limited choice: either we will win, or we will cease to exist. We must believe in victory and do everything for it. To be more pragmatic, for the first time in Ukrainian history, we are in a situation where almost the entire Western world is supporting us, so this time it will end well.

Several international organizations helped the Territory of Terror museum survive the winter of 2022 when another serious challenge — in addition to the shelling of the city — was widespread power outages due to the occupiers deliberately destroying the critical civil infrastructure of Ukraine. The museum received grants for generators, power banks, and also purchased personal protective equipment for workers in case of chemical and nuclear attacks.

In 2023, with the support of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, the museum continues the Wounded Culture project, recording interviews with museum workers about their experiences during the early days of the full-scale war and how they preserved the collections. A separate initiative is VR tours of the museums destroyed by Russia. The first such object was the Okhtyr Museum in the Slobozhanshchyna region. The director of Territory of Terror, Olha, says that it works well for foreign audiences who will not be able to see everything with their own eyes any time soon. Technology allows us to share the truth with them.

Under the conditions of Russian missile attacks and constant drone attacks on peaceful cities, any building can be damaged or destroyed, including those with architectural or historical value. Fortunately, there are teams that professionally help preserve this cultural heritage for the future. Among them is the Lviv startup Skeiron that scans objects of cultural heritage, in particular museums and their exhibits. Such scans are helpful during restoration and important for heritage documentation. The Skeiron team is working with the Territory of Terror museum to help protect their collections from irretrievable loss.

Olha emphasizes that in the international context, they not only focus on preservation but also contribute to the promotion of museums, a lesson learned during the pandemic. Some of the scanned pictures are used in merchandise, including magnets, t-shirts, notebooks, and even stickers.

— If we talk about us (Ukrainian museums — ed.), this is purely a matter of security. The more we manage to scan in this situation of complete chaos, the more likely it will be preserved at all.

One of the tasks of the museum is to preserve memory. Unheard is a project that collects the oral testimonies from residents of Lviv and West of Ukraine who have experienced deportations, repressions, life in exile and were able to return to Ukraine. Most of these heroes are elderly individuals who recount the impact of the USSR’s totalitarian regime on their lives.

— The name of the project is Unheard, because most of the storytellers are non-public people. Many of them told their life stories only once, only to us.

After the full-scale invasion, the project continued to live but decreased in scale. The project’s authors are considering reformatting it to record the life experiences of people during the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war. Museum workers are aware of how human memory suppresses tragic events, and those who commit crimes often try to quickly cover their tracks and silence their victims. Olha notes that this is how they distorted the memory of entire generations, portraying the World War II as a great Russian victory rather than a tragedy for all of humanity. According to her, many of those interviewed for the Unheard project did not share their experiences with their families.

— In our country, every generation has tried to escape Russia, every generation has lost something because of Russia, and every generation resisted the totalitarian regime. The experience of resistance is conveyed through these narratives.

The director of Territory of Terror notes that visibility is the essential thing that distinguishes the current situation from the one in which Ukrainians found themselves during the Soviet era. From the first days of the full-scale invasion, Ukrainians have been telling the world about Russia’s crimes and their consequences. Olha believes that only the grandsons of the storytellers will be able to objectively reflect on what was collected in their Unheard project because everyone who lives in Ukraine today is traumatized by the war in one way or another.

Yurii Kodenko, a senior researcher at the Territory of Terror museum, fills the exhibitions with information and researches the history of terror in Ukraine. His experience as an historian prompted him to leave Luhansk in 2014, where lists of pro-Ukrainian people had already begun to be drawn up. He packed his belongings into two bags and left the house, not knowing when he would be able to return. Work helped him adapt to new surroundings.

— After so many years, I’ve noticed that I now say “in our Lviv.”

Yurii’s primary focus is on the oral history projects of the museum, where he interviews people who survived repressions. He emphasizes that the museum is not only about evaluating people’s actions from the point of view of modernity, but also covers events as they happened — that is, using a historical approach. This is essential for reconstructing a comprehensive picture of events.

Memory is influenced by time, and the human psyche often displaces and distorts traumatic events, leading to confusion in their sequence. Yurii recalls that in some cases it works like this: a person was really active in underground organizations, and was caught by the punitive authorities. Now they have an ordinary life, which seems uninteresting, so they begin to embellish the past. n this situation, historians’ task is to verify the evidence.

Yurii says that Russia will be hostile to Ukraine until it changes, but this process is extremely difficult and long-term, because they must finally realize that their “history” is a lie, and Ukrainians are not and have never been part of the Russian people. Yurii believes that there is currently no indication that this process has started.

— We are watching Putin’s regime transform from an authoritarian to a totalitarian one – the same as in Stalin’s time, almost one-to-one.

Yurii is confident that the Ukrainians will win this war because the Russians subconsciously understand that they are the aggressors, constantly needing to search for motivation to continue. Ukrainians, defending their land, are motivated to fight.

— An unjust war is an act of aggression, whereas a just war is defensive. When people defend their land, their homes, and their families, it inspires them, leading to unexpected capabilities.

At a time when the world is coming to understand that Ukraine is distinct from Russia, neither a part of it nor a “brotherly nation”, it becomes essential to articulate what our country is, how it has been shaped, and its influence on the formation of the global community. Therefore, according to Olha, culture is important. In addition, it translates into ammunition thanks to various charity auctions in support of the Armed Forces.

The head of the Territory of Terror museum emphasizes that the understanding of the importance of culture among those in power also plays a significant role.

— As long as we pinch pennies on this (culture — ed.) at the state level, the war will keep returning. We should not have a situation when such organizations as the Ukrainian Cultural Fund declare that they have no money, or museums are forced to lay off people due to underfunding in such a difficult time.

According to Olha, what distinguishes Russians from Ukrainians is their lack of critical thinking and fixation on the long past. In order for culture to develop, dialogue, discussion, and freedom of speech are needed — but there is none of that. She notes that the Russians made a miscalculation when they expected Ukrainians, frightened and divided by a full-scale invasion, to act on the principle of “let someone else deal with this.” Yes, Ukrainians do quarrel with each other, but when it comes to matters important to the whole community or nation, they protest, strike, criticize the government, etc. That is, they express an opinion, and this gives birth to the truth; when it is necessary to unite, personal quarrels take a back seat.

— Kyiv does not decide for all regions. Our country is vast and diverse, and our strength lies in self-government.

Since the full-scale invasion, Olha has been on many foreign trips where she gave talks about the situation with museums in Ukraine. She mantions that she did not meet any so-called “good Russians,” but there was always someone who said something like, “Why should we only hear one side, the Ukrainian one? I also want to hear from Russian liberals.” Olha responded to such accusations with two arguments. Firstly, that this situation is not about two sides and finding justice, because such a view does not take into account that there was aggression against a peaceful country. And secondly, she directly asked what Russian liberals have done during their years abroad, often funded by Europeans themselves.

In comparison to Kharkiv or Kyiv, Lviv experiences fewer attacks from the Russian army. This is why it has become a hub for journalists and diplomats, as well as a destination for many people who have relocated from cities severely affected by the war.

— It so happens that for now there are fewer missile strikes here (in Lviv — ed.) than in other places. This means that we have to help all those who have suffered more, shelter them here or help them to move further. We must become mediators between foreigners and those who need help, and keep working tirelessly. It is good that Ukraine is big, and people have the opportunity to move around while staying within our borders.

Lviv felt the impact of the full-scale war most strongly in the first months of the invasion and during the winter blackouts. But the war remains present in this western city: she constantly sees the funerals of her soldiers, and welcomes back wounded veterans while others leave the city for the front.

Olha is confident of victory and says that she wants to watch Russian evil disintegrate.

— Ukrainians will win this war because we are already experienced warriors. This war has not been going on since February 24th or even for the last nine years, this war has been going on for a very, very long time. Every generation in our country experienced loss, fought, and resisted Russian occupation. And finally, it’s time to put an end to this story.

supported by

Due to the full-scale war, Ukrainian museums with priceless exhibits were threatened with destruction. Some of them are under occupation and have already been looted by the Russians; some have suffered from shelling, and museum workers are forced to leave their hometowns, which is why not everyone manages to stay in the profession. Those who are far from hostilities managed to evacuate or hide all or at least part of the museum fund but work with reduced funding. In the summer of 2023, the Ukraïner team went on an expedition to investigate culture during war: how wartime realities change it, how it reflects new circumstances, and whether it manages to remain the heart of society, as before. This is how the documentary project Culture during the War began: a series of videos and long-form articles from different regions of Ukraine: West, East, North, South, and Center. The first series centres on the West and consists of two parts. The first one is dedicated to Andriy Lyubka, the writer and translator from Uzhgorod, who has become a volunteer raising funds for vehicles for the Armed Forces. This article is about two most notable museums in the West of Ukraine: Korsaks’ Museum of Modern Ukrainian Art in Lutsk and Territory of Terror, Lviv Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, both have become spaces where artists, together with visitors, can rethink the ongoing events, seeking solace and support in art. Korsaks’ Museum in Lutsk The city of Lutsk, in Volyn, is famous, above all, thanks to Lubart Castle. However, since 2018, tourists have been coming to Lutsk to visit Korsaks’ Museum of Ukrainian Modern Art. It houses both a permanent art-memorial exhibition of Mykola Kumanovskyi and a rotating exhibition. The museum also hosts a library of art literature, two conference halls, and a gallery of street art called PolychromA (in 2016, the team of the Art-kafedra galley, the original organizers of the museum, organized an eponymous festival of modern urban art). Mykola KumanovskyiAn artist from Ukraine, originally hailing from the village of Sataniv in Podillia, has been residing and working in Lutsk since the 1970s. His creative studio has become a significant cultural and artistic hub in the city. He was involved in easel painting, graphics, sculpture, illustrated printed publications, theater performance design, and the organization of art exhibitions featuring innovative ideas for his time. With the beginning of the full-scale invasion in 2022, most of the collection was moved to a safe location, but the museum continues to operate and bring modern art to the people by regularly arranging various exhibitions of Ukrainian artists. The museum was founded by the surgeon and businessman Viktor Korsak. When he defended his PhD thesis in 1997, a surgeon’s salary was four dollars per month. To support his two children, Viktor initially worked as a porter at night while practicing surgery during the day. Eventually, he decided to venture into business. The work of Lutsk artist Mykola Kumanovskyi was hanging in Viktor’s office, and a friend noticed it, saying that he would like it for himself. Viktor got to know the artist and bought not just one, but several works from him. First, they hung in his home, but later he opened an exhibition at his Adrenaline City shopping and entertainment complex. This initiative eventually evolved into the modern art museum that bears his family name. It appears that Viktor Korsak’s friendship with Mykola Kumanovskyi inspired him to create a gallery of contemporary Ukrainian art. The collection of Kumanovskyi’s works became the foundation and the beginning of Lutsk’s first private art collection. Today, Viktor serves as both the museum’s founder and its driving force. — Our museum’s mission is to reflect on the past, change the present, and create the future. The main goal is for a person to enter the museum and leave somewhat changed. The museum operates based on three core principles”: Concept, Collaboration, and Communication. Pavlo KovachA Ukrainian artist hailing from Uzhhorod. His talents encompass painting, graphic art, performance art, and restoration work. He is a member of the Poptrans art group, a co-founder of the Corridor Gallery, and holds membership in the Union of Artists of Ukraine. On the evening of February 23, 2022, the museum opened the exhibition The Wall by Pavlo Kovach. On the third day of the full-scale war, he began to disseminate first aid to the residents of Lutsk. His supermarket chain collected 30,000 food kits, and his hotel chain provided shelter for those fleeing the war, including ten artists. Meanwhile, his wife and daughter-in-law packed the museum’s collection, though not in its entirety: — Art is a form of communication with the viewer. That is why I have paintings in offices, clinics and hotels. People have to be able to see it, that’s the only way it affects people. A jug that is in storage is just a jug, but if it enters the context of an exhibition hall it is a work of art, an exhibit. Since November 2022, the museum has been working on a huge project called Cosmogony. The concept is to paint a picture with an area of two thousand square meters, making it the largest in the world. Its creation will also set a record for the longest time to paint a work. The artist behind this project is Petro Antyp, hailing from Horlivka in the Donetsk region. Also part of the project are thematic exhibitions of Ukrainian artists, and 500 applicants have already submitted their works to a panel of experts. They plan to create pictures with the help of artificial intelligence. Viktor mentions that if the Guinness Book of Records shows interest in the museum’s painting, he welcomes it as it would provide valuable publicity for Ukraine. — You can hold a hundred exhibitions in small galleries around the world, and this will absolutely not affect the image of Ukraine as a country of real high-quality modern art. And you can make one such project, and the world will talk about it. We plan to do so. We should enter world art not to be pitied, but to show something that no one in the world has done. When [Volodymyr] Klytschko became the [world] boxing champion, people started talking about Ukraine as a home to Klitschko, not just as the site of the Chornobyl disaster. Viktor is worried about the image of Ukrainian art now that many artists have left due to the full-scale war and are exhibiting and selling their works abroad. According to him, charity initiatives are often not about the highest quality work. Such works are bought to help Ukraine, but this creates an impression of modern Ukrainian art as mediocre. It is important for artists to remember, Viktor emphasizes, that they are representatives of Ukrainian art abroad, so they bear a certain responsibility for the cultural image of Ukraine. Viktor himself does not paint pictures, but is an art connoisseur and tries himself in various roles, including curator. He was inspired by the philosophy of the French thinker and writer Michel de Montaigne to create another art project, the exhibition Thoughts and a part of the Cosmogony project. It raises existential questions about life, death, conscience and war. Exhibits are selected for each of Viktor Korsak’s forty thoughts, including paintings and sculptures combined with background music. The artist calls it a kind of pressure of art on a person, when various receptors for the perception of information are activated. When writing a synopsis of thoughts, Victor used a modern way to speed up this process — ChatGPT. — In Thoughts, people have responded to the tank in the shape of a greenhouse the most: on one side is war, and on the other is living and invincible greenery. ChatGPTA chatbot with artificial intelligence that can work with text, program code, formulas, and numbers, and generate anything it is asked to. Art performs a therapeutic function not only for the one who creates, but also for the one who perceives it. To understand modern art, according to Viktor, aesthetic intelligence is needed. And to develop it – three things: observation, interaction, and your own creativity. — Sometimes they ask me: “Look at abstract art, what do you see there?”. You don’t need to see anything there! I always ask in response: “When you look at the sunset, what do you see there?”. This is how you should look at abstract art. Viktor observes that the war has led to the creation of numerous opportunistic works, which cannot truly be called art and are destined to be forgotten, much like what occurred with the Soviet ideological heritage. Instead, he is certain that Ukraine must reclaim its cultural heritage by ensuring that the works of artists like Kazimir Malevych, Ilya Ripyn (known as Repin), Oleksandr Arkhipenko, and others are recognized as part of our country’s heritage and can be studied here. For centuries, Russia destroyed Ukrainian art or appropriated its achievements. Viktor emphasizes that modern Ukrainian cultural figures need to be bold and assertive because small steps won’t lead us anywhere. Petro Antyp, the creator of the painting Cosmogony, paints daily, and is involved in sculpture. He believes that self-organization is essential for an artist to accomplish anything. He points out that the phrase “an artist must be hungry” has Russian origins and should be avoided. — I went to many workshops in Europe, saw how the French and Germans work. Everything is clean and tidy with them, their portfolio shows what they have done, what they are thinking of doing, everything is clear. It’s essential to replace the Russian and Soviet mentality, where art was defined by the tsar, the party, or Putin, while in Europe, what distinguishes an artist is their freedom, and their ideas are unbound. Petro is sure that artificial intelligence will never surpass a real artist. While some may appreciate “algorithmic” paintings, an artist can synthesize ideas from past and present knowledge, as well as from their unique experiences and worldview. Petro is interested in the myths of various peoples of the world and interprets them in his works. In the painting Cosmogony, he started with the way the birth of the earth was once described: — In Egyptian myths, a rabbit killed a snake, and a tree grew. It is in my painting: the Sky is his breath, the Moon is one eye, the Sun is the other. According to Petro, there is a problem with art education in Ukraine, because most teachers do not focus on the world of the student, but train a craftsman who knows technique but does not know how to express themselves in their work. Above all else, freedom should be paramount for Ukrainian artists. Petro’s grandfather is an artist, and from a young age the artist loved the smell of paint. He started painting early and received his art education in the Russian city of Penza. He says that at his home, in Horlivka, they spoke a mix of Russian and Ukrainian, while Ukrainian schools were closed. Only in Russia was he told that he was Ukrainian. There, Petro began to unite with other Ukrainians who studied with him. He was preparing to enter the academy in Moscow but he went home after an incident. — An academic named Chesovitin said to me: “Why do you want to join the Academy? It’s better to go to the Union of Artists and live in Moscow. The most important thing is: do not go to Ukraine, as khokhly (derogatory name for Ukrainians — ed.) have no wings.” This phrase made everything clear to me, so I turned around and went home. At home, Petro got acquainted with Ukrainian art, the names of masters whom he did not know before, and realized that Ukrainian art is amazing. He began to travel the world, while also working in Horlivka. Russian aggression (in 2014 — ed.) forced him to leave his home, workshop, and business. Although his paintings were rescued, but his sculptures had to be left behind. Stoic philosophy helped him survive the loss of his home, and he decided to start life with a clean slate. He believes that nothing belongs to a person except his own emotions and thoughts, and they can be controlled. StoicismA philosophical tradition that emerged in ancient Greece in the third century BC. Its main ideas include controlling one's emotions, thinking rationally, accepting necessity and nature, and developing morality. Currently, in Petro’s opinion, Ukrainian artists face a signidicat challenge. Despite all the military victories, Ukraine cannot truly be recognized as a great power without presenting its culture to the world. Fortunately, there is much to present: — In our country, every woman who paints eggs for Easter is an artist. We have such embroidery! Petro notes that there are many grants for Ukrainian artists as refugees but they do not open Ukrainian art to the world, because this can only be done with big, bold projects. And it is better to make two powerful ones than to scatter on thirty. Artists will continue to reflect on the Russian-Ukrainian war in their works for a long time. Petro hopes they will not only highlight the tragedy but also emphasize heroism. — The 300 Spartans lost everything, but they are heroes who did a feat. Our Mariupol is also a feat. I want to paint a true, strong Ukraine so that people are proud of it. Artists cannot be outside of politics. If they are public, they are already a part of politics, even if they do not feel or realize it, Petro believes. — Wasn’t Taras Shevchenko involved in politics? Ivan Franko as well? And Vasyl Stus? Name me an artist who remained completely apolitical. Read Ripyn’s diaries, what he wrote about Russians. In galleries, encyclopedias and collections, the nationality of artists is indicated. Petro urges Ukrainians to return the names that were intentionally misappropriated by Russia. Once, he was flipping through a Russian portfolio where a thousand artists were presented, and their nationality was indicated everywhere. However, the thirty Ukrainians who were among them were labeled as Russian or simply “born in Melitopol / Odesa / another city.” It is surprising that this was compiled by professionals. Ukrainians underestimated themselves for a long time, and Russians took advantage of this. But now Ukrainians are rethinking their culture, studying history and getting to know themselves, so the artist sees a bright future: — I think that Ukraine will have a great future. Everything is going to be fine with us. Territory of Terror museum in Lviv Olha Honchar is the director of the Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes Territory of Terror, located on the site of the former Lviv ghetto, the third largest in the Third Reich, which existed from 1941 to 1943. The museum was opened in 2017 and consists of an exhibition and a space for discussions and presentations. Visitors will see a “cattle carriage” (people were deported in such carriages), reconstructions of a typical Lviv resident’s home in the 1920s and 1930s, bedrooms after a search, arrest or deportation, a camp barracks, and a Soviet archive where there was a case file for every arrested person. One of the parts of the exposition that is constantly replenished is a collection of monumental Soviet art, where decommunized monuments are taken after being removed from public spaces. — When there are such museums, history does not seem to be black and white, it does not seem to be gray, it is just confusing; however it clearly shows how a person can resist and remain human. From February 24 to September of 2022, the museum was closed to visitors but employees conducted tours about the history of the city for internally displaced persons. Part of the team evacuated abroad, so new staff began working in the museum. At midnight, before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Olha was brainstorming a potential evacuation with a colleague from the Starobilsk Museum in Slobozhanshchyna. By eight o’clock in the morning of the next day, together with the team of her museum, she was already packing exhibits. Some documents were already digitized, valuables were concealed, and windows were taped shut. They also sought out places that could accommodate displaced people from other cities. — Since the first days of the war, Lviv became a logistical hub. Everyone I knew from the museum field including international partners called us because we could be reached, as others were either on the road or under fire. The first weeks of the full-scale war saw the creation of the Museum Crisis Center, an initiative that has been helping museum workers ever since, including financial support during evacuation. More than a hundred museums across ten regions (mostly Donetsk region, Kherson region, Sivershchyna region, and Slobozhanshchyna region) have already been helped. — Currently, the life of [any] museum in Ukraine depends on its territorial location: the further from Russia, the better. Those located closer to the border are either occupied or destroyed. Farther from the border, events and art therapy are held even in empty premises. Throughout 2022, the Territory of Terror museum worked to preserve their collection and digitize exhibits. Thanks to the audio guide in Ukrainian and English, you can learn about their museum objects in any corner of the world. — It is important for us to have a copy of the museum on a flash drive, so that if something happens, there is something to restore. Taras Rizun is the chief custodian of the collection of the Territory of Terror museum. He is responsible for recording and storing the exhibits, as well as scanned data on electronic media. Taras was directly involved in process of scanning the exhibits. A 3D tour of the museum can be seen on the museum’s website. As of 2023, there are already 50 of the most valuable exhibits available, with brief descriptions. Taras notes that being able to visit the museum from home encourages people to visit it in person. — Creating a 3D model of a single exhibit requires taking hundreds of pictures from various angles. An example comes to mind: a 3D model of a shirt by Olha Popadyn, which she embroidered while she was in prison on Lontsky Street in the 1950s. This shirt could not be scanned simply by hanging it on a hanger or holding it in your hands. We put it on a mannequin, and the guys with cameras literally danced around it: we filmed from above, from the sides, and from below. Olha PopadynMember of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). She was convicted in the “Trial 59” of 1941. At that time, 59 young Ukrainians, mostly students of Lviv universities, were brought to trial. They were accused of belonging to the OUN, of anti-Soviet activities and of preparing an uprising against the Soviet regime. In times of war the museum cannot function as it did during times of peace. The primary focus of activity shifts to preserving the collection and offering mutual assistance. Taras notes that if the Russians wanted to be honest with themselves, they would have to derive their history from other sources. And as long as they do it on the basis of stolen material, they will want to destroy Ukrainians. Despite the war, theaters continue to operate, writers are producing books, publishers are releasing them, and artists are creating paintings. Cultural life continues, but institutions are more difficult — they are less nimble than a business or an independent artist. They rely on funding and require state protection, which is currently primarily focused on the war effort. — On the banner of the Kholodnyi Yar rebels was written “Freedom or Death.” We have a limited choice: either we will win, or we will cease to exist. We must believe in victory and do everything for it. To be more pragmatic, for the first time in Ukrainian history, we are in a situation where almost the entire Western world is supporting us, so this time it will end well. Several international organizations helped the Territory of Terror museum survive the winter of 2022 when another serious challenge — in addition to the shelling of the city — was widespread power outages due to the occupiers deliberately destroying the critical civil infrastructure of Ukraine. The museum received grants for generators, power banks, and also purchased personal protective equipment for workers in case of chemical and nuclear attacks. In 2023, with the support of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, the museum continues the Wounded Culture project, recording interviews with museum workers about their experiences during the early days of the full-scale war and how they preserved the collections. A separate initiative is VR tours of the museums destroyed by Russia. The first such object was the Okhtyr Museum in the Slobozhanshchyna region. The director of Territory of Terror, Olha, says that it works well for foreign audiences who will not be able to see everything with their own eyes any time soon. Technology allows us to share the truth with them. Under the conditions of Russian missile attacks and constant drone attacks on peaceful cities, any building can be damaged or destroyed, including those with architectural or historical value. Fortunately, there are teams that professionally help preserve this cultural heritage for the future. Among them is the Lviv startup Skeiron that scans objects of cultural heritage, in particular museums and their exhibits. Such scans are helpful during restoration and important for heritage documentation. The Skeiron team is working with the Territory of Terror museum to help protect their collections from irretrievable loss. Olha emphasizes that in the international context, they not only focus on preservation but also contribute to the promotion of museums, a lesson learned during the pandemic. Some of the scanned pictures are used in merchandise, including magnets, t-shirts, notebooks, and even stickers. — If we talk about us (Ukrainian museums — ed.), this is purely a matter of security. The more we manage to scan in this situation of complete chaos, the more likely it will be preserved at all. One of the tasks of the museum is to preserve memory. Unheard is a project that collects the oral testimonies from residents of Lviv and West of Ukraine who have experienced deportations, repressions, life in exile and were able to return to Ukraine. Most of these heroes are elderly individuals who recount the impact of the USSR’s totalitarian regime on their lives. — The name of the project is Unheard, because most of the storytellers are non-public people. Many of them told their life stories only once, only to us. After the full-scale invasion, the project continued to live but decreased in scale. The project’s authors are considering reformatting it to record the life experiences of people during the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war. Museum workers are aware of how human memory suppresses tragic events, and those who commit crimes often try to quickly cover their tracks and silence their victims. Olha notes that this is how they distorted the memory of entire generations, portraying the World War II as a great Russian victory rather than a tragedy for all of humanity. According to her, many of those interviewed for the Unheard project did not share their experiences with their families. — In our country, every generation has tried to escape Russia, every generation has lost something because of Russia, and every generation resisted the totalitarian regime. The experience of resistance is conveyed through these narratives. The director of Territory of Terror notes that visibility is the essential thing that distinguishes the current situation from the one in which Ukrainians found themselves during the Soviet era. From the first days of the full-scale invasion, Ukrainians have been telling the world about Russia’s crimes and their consequences. Olha believes that only the grandsons of the storytellers will be able to objectively reflect on what was collected in their Unheard project because everyone who lives in Ukraine today is traumatized by the war in one way or another. Yurii Kodenko, a senior researcher at the Territory of Terror museum, fills the exhibitions with information and researches the history of terror in Ukraine. His experience as an historian prompted him to leave Luhansk in 2014, where lists of pro-Ukrainian people had already begun to be drawn up. He packed his belongings into two bags and left the house, not knowing when he would be able to return. Work helped him adapt to new surroundings. — After so many years, I’ve noticed that I now say “in our Lviv.” Yurii’s primary focus is on the oral history projects of the museum, where he interviews people who survived repressions. He emphasizes that the museum is not only about evaluating people’s actions from the point of view of modernity, but also covers events as they happened — that is, using a historical approach. This is essential for reconstructing a comprehensive picture of events. Memory is influenced by time, and the human psyche often displaces and distorts traumatic events, leading to confusion in their sequence. Yurii recalls that in some cases it works like this: a person was really active in underground organizations, and was caught by the punitive authorities. Now they have an ordinary life, which seems uninteresting, so they begin to embellish the past. n this situation, historians’ task is to verify the evidence. Yurii says that Russia will be hostile to Ukraine until it changes, but this process is extremely difficult and long-term, because they must finally realize that their “history” is a lie, and Ukrainians are not and have never been part of the Russian people. Yurii believes that there is currently no indication that this process has started. — We are watching Putin’s regime transform from an authoritarian to a totalitarian one – the same as in Stalin’s time, almost one-to-one. Yurii is confident that the Ukrainians will win this war because the Russians subconsciously understand that they are the aggressors, constantly needing to search for motivation to continue. Ukrainians, defending their land, are motivated to fight. — An unjust war is an act of aggression, whereas a just war is defensive. When people defend their land, their homes, and their families, it inspires them, leading to unexpected capabilities. At a time when the world is coming to understand that Ukraine is distinct from Russia, neither a part of it nor a “brotherly nation”, it becomes essential to articulate what our country is, how it has been shaped, and its influence on the formation of the global community. Therefore, according to Olha, culture is important. In addition, it translates into ammunition thanks to various charity auctions in support of the Armed Forces. The head of the Territory of Terror museum emphasizes that the understanding of the importance of culture among those in power also plays a significant role. — As long as we pinch pennies on this (culture — ed.) at the state level, the war will keep returning. We should not have a situation when such organizations as the Ukrainian Cultural Fund declare that they have no money, or museums are forced to lay off people due to underfunding in such a difficult time. According to Olha, what distinguishes Russians from Ukrainians is their lack of critical thinking and fixation on the long past. In order for culture to develop, dialogue, discussion, and freedom of speech are needed — but there is none of that. She notes that the Russians made a miscalculation when they expected Ukrainians, frightened and divided by a full-scale invasion, to act on the principle of “let someone else deal with this.” Yes, Ukrainians do quarrel with each other, but when it comes to matters important to the whole community or nation, they protest, strike, criticize the government, etc. That is, they express an opinion, and this gives birth to the truth; when it is necessary to unite, personal quarrels take a back seat. — Kyiv does not decide for all regions. Our country is vast and diverse, and our strength lies in self-government. Since the full-scale invasion, Olha has been on many foreign trips where she gave talks about the situation with museums in Ukraine. She mantions that she did not meet any so-called “good Russians,” but there was always someone who said something like, “Why should we only hear one side, the Ukrainian one? I also want to hear from Russian liberals.” Olha responded to such accusations with two arguments. Firstly, that this situation is not about two sides and finding justice, because such a view does not take into account that there was aggression against a peaceful country. And secondly, she directly asked what Russian liberals have done during their years abroad, often funded by Europeans themselves. In comparison to Kharkiv or Kyiv, Lviv experiences fewer attacks from the Russian army. This is why it has become a hub for journalists and diplomats, as well as a destination for many people who have relocated from cities severely affected by the war. — It so happens that for now there are fewer missile strikes here (in Lviv — ed.) than in other places. This means that we have to help all those who have suffered more, shelter them here or help them to move further. We must become mediators between foreigners and those who need help, and keep working tirelessly. It is good that Ukraine is big, and people have the opportunity to move around while staying within our borders. Lviv felt the impact of the full-scale war most strongly in the first months of the invasion and during the winter blackouts. But the war remains present in this western city: she constantly sees the funerals of her soldiers, and welcomes back wounded veterans while others leave the city for the front. Olha is confident of victory and says that she wants to watch Russian evil disintegrate. — Ukrainians will win this war because we are already experienced warriors. This war has not been going on since February 24th or even for the last nine years, this war has been going on for a very, very long time. Every generation in our country experienced loss, fought, and resisted Russian occupation. And finally, it’s time to put an end to this story. Founder of Ukraїner: Bogdan LogvynenkoAuthor: Sofiia KotovychEditor-in-chief: Anna YabluchnaEditor: Lisa PalchynskaPhotographer: Sofia SoliarPhoto editor: Yurii StefanyakTranscriptionist: Vitalii KravchenkoTaras BerezyukRoman AzhniukTranscriptionist: Diana StukanAnna LukasevychTetiana ProdanetsContent manager: Kateryna Minkina