Russian occupiers commit a terrible crime by deporting Ukrainians. Since the beginning of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian authorities and their accomplices (in particular, local collaborators) have been organizing mass deportations by forcibly transferring Ukrainians deep into the Russian Federation’s territory and the Republic of Belarus.

Since March 2022, Ukrainians have recorded numerous cases of deportation of Ukrainian citizens by Russian forces. The report of the human rights Coalition “Ukraine. 5 am” of January 16, 2023, states that the number of deported Ukrainians to Russia varies from 2.8 to 4.7 million, of whom 260 to 700 thousand are children.

At the same time, the Russian mass media actively spread disinformation, using its usual tactic of misrepresenting the facts. They call the forcible transfer of Ukrainians “evacuation,” and the victims — “refugees.”

Deportation is an unlawful way to subjugate and exterminate the population of the occupied territories. The Russian Federation has been using this method of invading countries for decades. Modern Russia, as the successor of the Soviet Union, conducts its foreign policy in the most shameful Soviet traditions, committing the same crimes as the communists in the 20th century. To show the durability of this cruel deportation tradition, we will look at cases of forced eviction of various peoples from Soviet times to nowadays.

Putin and Stalin. Source: Crimea. Realities.

Soviet deportations: subjugate and exterminate

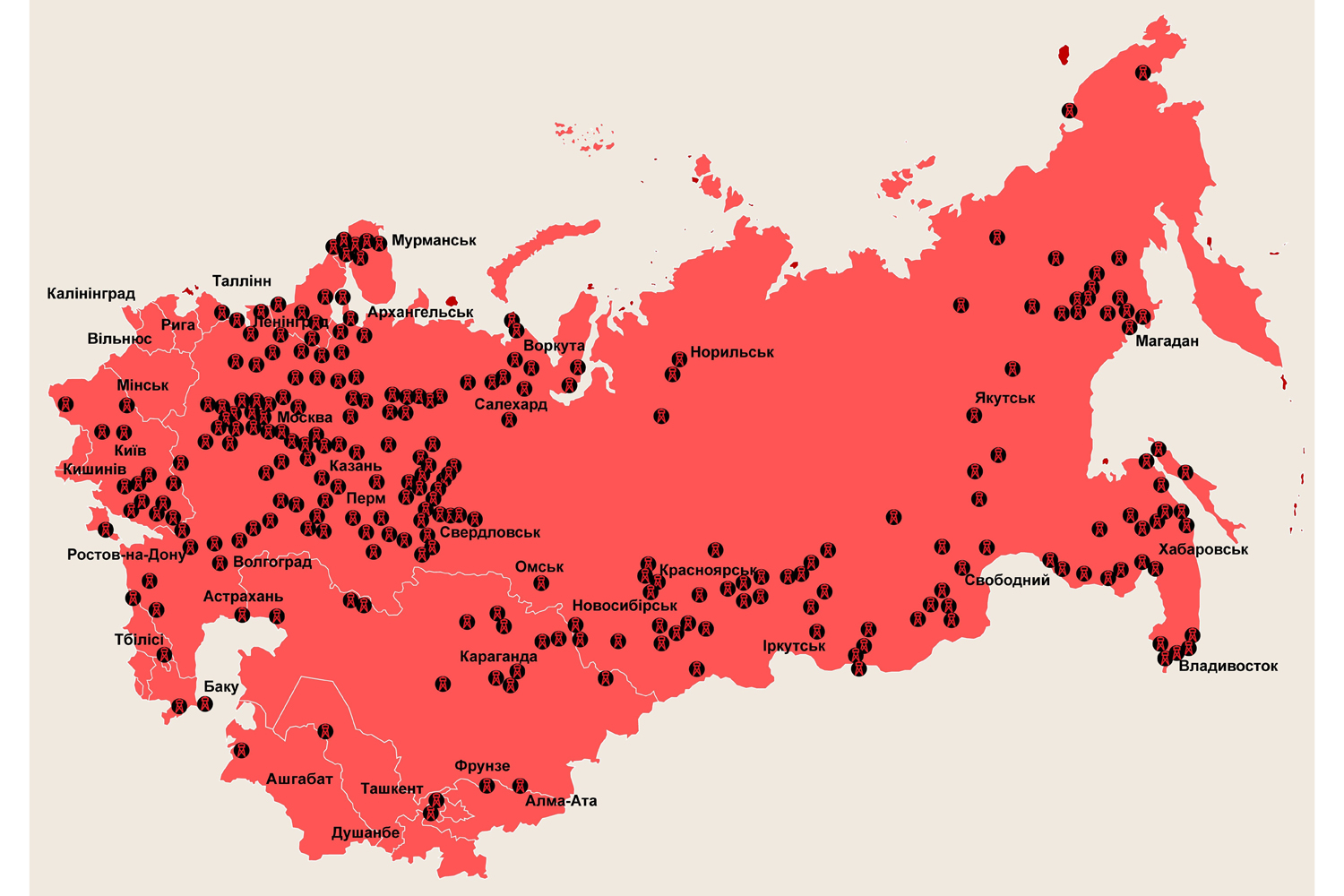

Over 69 years of the existence of the USSR, the communist punitive and repressive bodies conducted about 110 deportations, which led to the forcible resettlement of almost 6 million innocent people. The “Soviet people” were created by occupying the territories of independent countries, exterminating their educated elites, subjugation, and genocide. The USSR was full of concentration and labor camps, where the criminals in power ruined the lives of millions of people.

The map of Soviet concentration camps. Source: Radio Svoboda.

Deportations from the Baltic States

The Baltic countries saw two deportations in 1941 and 1949.

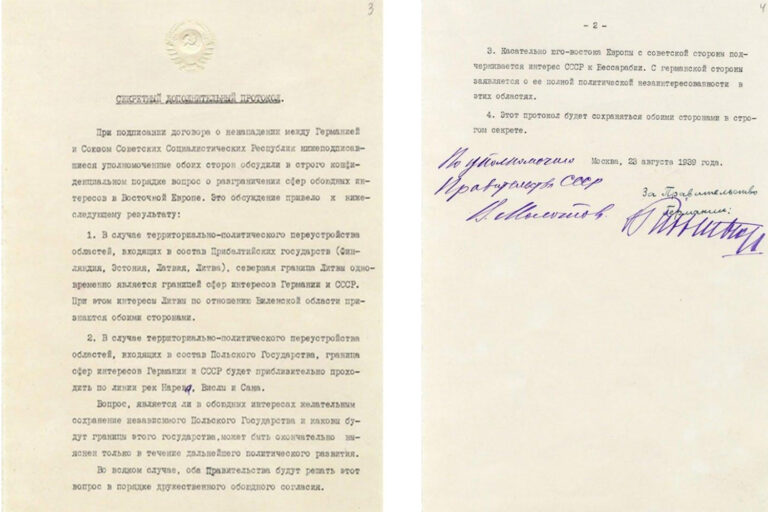

They were preceded by the Soviet occupation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1940. It all started in August 1939, when Germany and the USSR signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. According to its additional secret protocol, Estonia and Latvia were in the Soviet sphere of interest, while Lithuania was under Germany. This document marked the beginning of the occupation of three, then still independent, Baltic states.

slideshow

The Soviets began the forced eviction of the population of the Baltic countries in 1940, and by the summer of 1941, they became systematic. This was a carefully planned criminal act that clearly defined the groups subject to forced relocation.

The exact number of people to be deported from Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia is unknown. The June 1941 NKVD plan for the logistics, distribution, and use of deportees from the Soviet republics of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Moldova sets a goal of 74,395 people, including 46,557 households, 22,885 male heads of households, 4,159 criminals, and 794 women referred to as prostitutes.

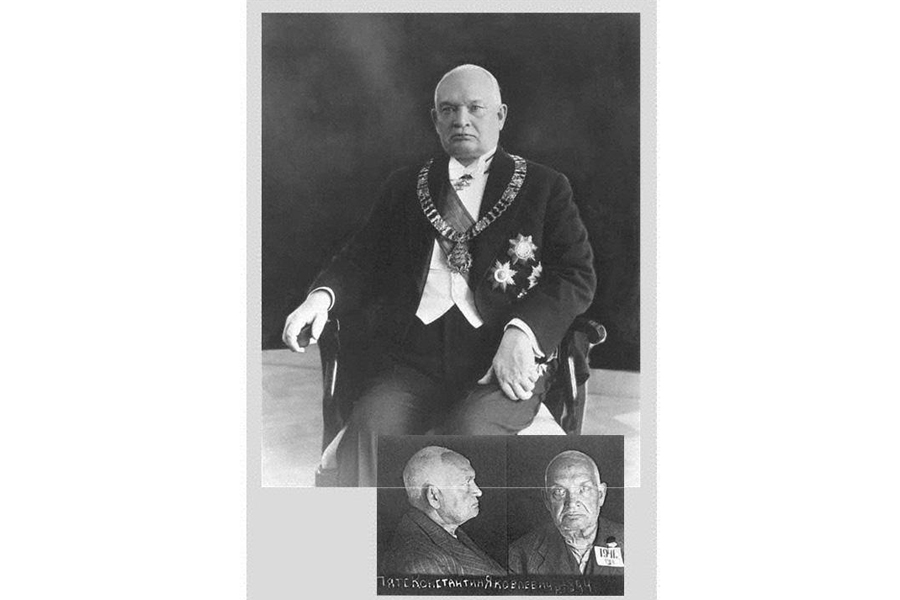

The deportation policy of the Soviet authorities unfolded with extraordinary speed. The first victims were the political leadership and the military elite. Only in July 1940, Konstantin Päts, the Estonian president, and Johan Laidoner, the Commander-in-Chief of the Estonian armed forces, were deported. Former Estonian statesmen also suffered: Friedrich Karl Akel, Jüri Jaakson, Jaan Tõnisson, and Jaan Teemant were killed, and four more died in prison.

NKVD

NKVD (the Russian abbreviation of The People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs) was the notorious law enforcement body of the Soviet government. It was created in 1917 and, in 1946, renamed as the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR.

Konstantin Päts, the President of the Republic of Estonia, before and after Soviet imprisonment. Photo from open sources.

The mass deportations of the population started soon after the eviction of the political leadership. These are Juhan Vaabel’s memories of the forced deportation of his family from Mulgimaa, a southern region of Estonia, to Siberia:

— We were deported to the village of Kosotyapka in the Tomsk Region, Russia. Our father was separated from us immediately upon arrival and taken to the Gulag on the banks of the Sosva River, where he died at age 38. <...> I learned about life in this camp from Mats Laarman, who passed this information onto the Academy of Sciences. <...> In the camp, everything was arranged so that it was possible to survive for only half a year. If someone managed to live longer, they were sent to work in the forest. They were deliberately sent there on foot by the longest route, and when they [the authorities] saw that a person would soon die, they directed them to walk through the swamp. If the direct path was five kilometers, then it was eight through the swamp. They hoped a person would die on the road near the swamp.

Gulag

The Russian acronym for the Main Administration of Correctional Labor Camps. It was the government network of correctional labor camps that existed in the Soviet Union in 1934–1956.He adds that dead people were piled near the swamp like firewood. In the spring, during the flood, these bodies sank in the mud. Juhan and his mother managed to get a permit to settle in the village of Novososnovka, Chayinsky district, Tomsk region, Russia. At that time, quite a lot of deported Estonians already lived there.

When the Red Army retreated from Latvia during the Soviet-German war, a telegram sent from Moscow to Riga on 13 June 1941 was found. According to the telegram, there was a plan to deport 11 102 Estonians.

Deportations also occurred in Latvia in June 1941, when the Soviet authorities deported about 15,400 Latvians to Siberia and Kazakhstan. Those evicted also were accused of “counter-revolutionary” and “anti-Soviet agitation,” which was often a fabrication. The wealthiest residents of the former Republic of Latvia were deported too.

Deportation of Latvian citizens on 14 June 1941.

The NKVD plans for deportations from the Lithuanian SSR are well documented. According to the memo of 11 June 1941 on the preparation of such forced transportation from Lithuania, 22 252 persons were subject to deportation. However, on the night of June 13-14, many more Lithuanians were deported, a total of 34 000 people.

The tragic history of the Red Terror unites the Baltic states in shared mourning for all the victims of this policy. Every year on 14 June, each country has a Remembrance Day: in Estonia, it is called the Day of Mourning and Commemoration (14. Juuni küuditamise mässätäpäev), in Lithuania it is the Day of Mourning and Hope (Gedulo ir vilties diena) and Latvia observes Commemoration Day for the Victims of Communist Genocide (Komunistiskā genocīda upuru piemiņas diena).

Deportation car at the station in Tornakalns district, Latvia, 1941. Photo: Edgars Ražinskis.

The Soviet authorities suspended deportations in the Baltic States only because of the active hostilities of World War II but resumed the brutal practice of forced resettlement in 1944 after returning to these territories.

The second mass deportation was organized in March 1949 under the code name Operation Priboi. Then part of the civilian population of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania was taken to Siberia and remote areas of the northern part of the USSR. It is believed that 94,779 people were deported, and the estimated mortality rate among deportees reached approximately 15%.

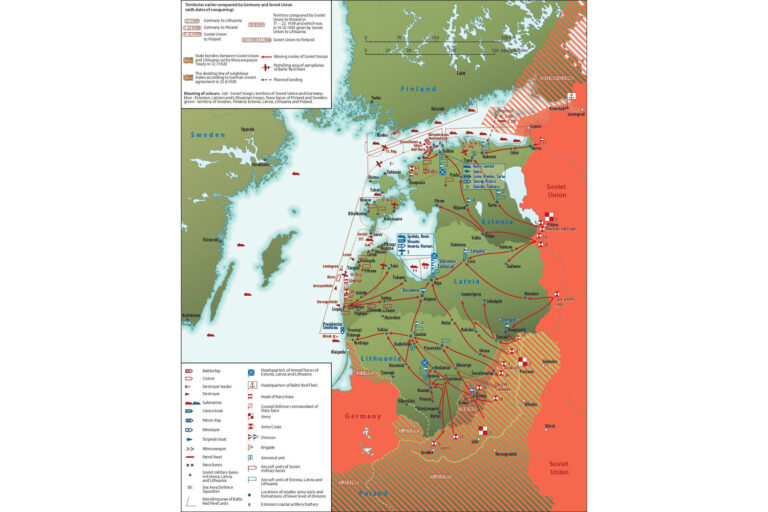

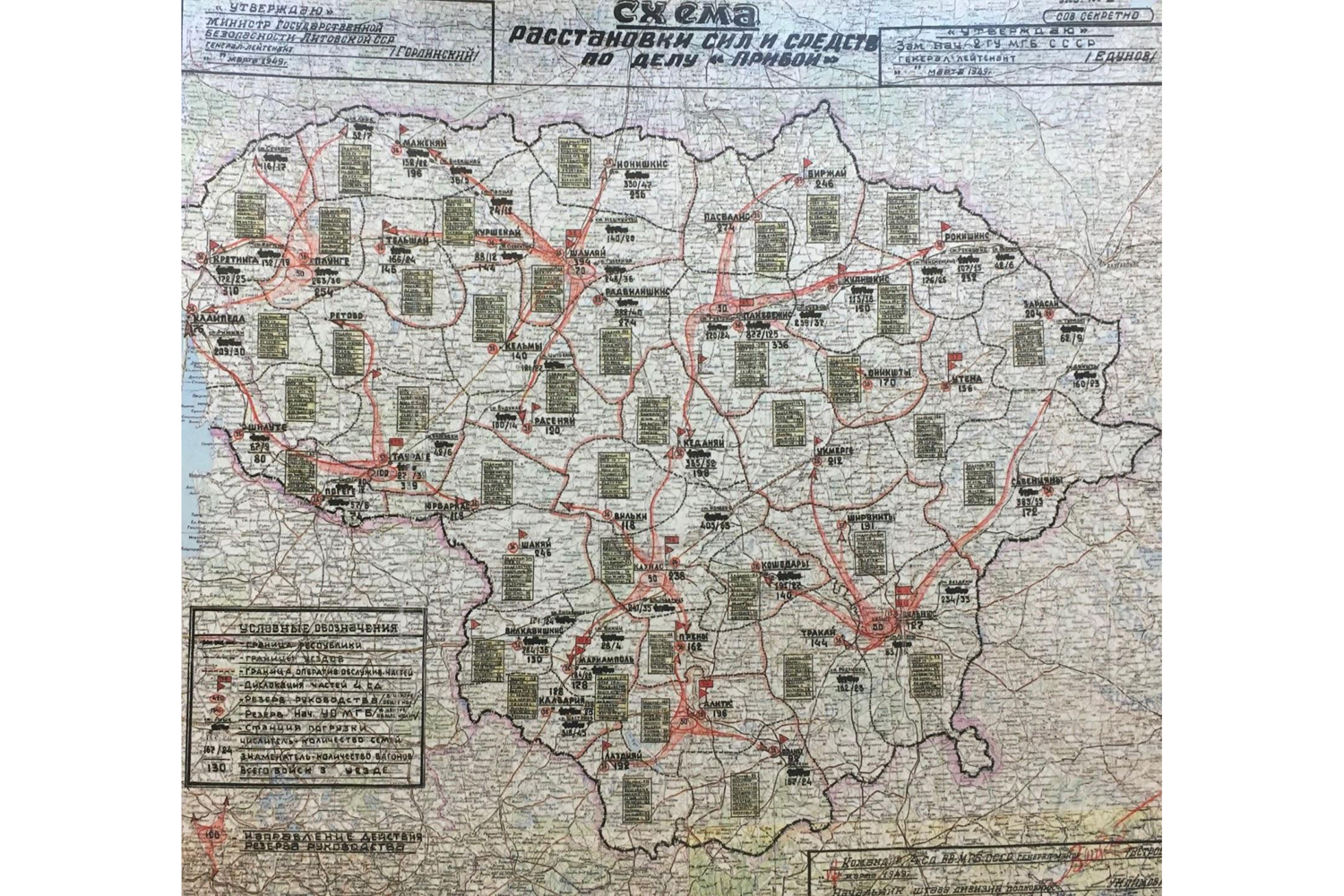

Diagram of the distribution of forces and means in the mass deportation operation Priboi. Source: Lietuvos Ypatingasis Archyvas.

Operation “Surf,” also called the “Great March Operation,” was launched by the Soviets on the night of 25 March. In the capitals of the Baltic countries, it started at 4:00 a.m.; from 6:00 a.m., it spread to the regions. It took three days to implement it.

According to the plan, the deportation was supposed to go as follows: task forces drove to the location from which they were supposed to stealthily approach and surround the house where the people from the deportation list lived. Then the group leader, with some soldiers, entered the house, checked who was there, searched the premises, and informed the head of the household about the eviction. The deportees and their belongings were brought to collection points at railway stations. From there, deportees were loaded in cattle wagons to be permanently transported to the special settlements. Communist Party members involved in the operation, along with collaborators, stayed in the homes of the deportees to take inventory of the property and hand it over to the local authorities. The property of the deportees was subject to confiscation.

In total, 7 488 households totaling 20 535 people, including 4 579 men, 9 890 women, and 6 066 children, were transported from Estonia to Siberia in 19 echelons in four days between 25 and 29 March 1949. However, the Soviet authorities failed to fully implement the plan because 1 791 people were lucky to hide. However, the authorities remembered them. After the end of the Priboi operation, the hunt for the fugitives went on for several months.

Deported Estonians, March, 1949. Photo from open sources.

According to Heinrichs Strods, professor at the University of Latvia, the Soviet authorities recruited 3 300 operatives, 8 313 servicemen of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs troops, and 9 800 soldiers of the Soviet Army to carry out Operation Priboi on the territory of Latvia. The Soviets used 31 railway trains, all consisting of freight cars, to transport people. In total, 13 624 households or 42,975 people were subject to deportation, primarily rural residents whom the Soviet authorities classified as “kulaks” (peasants who owned land) or accomplices of the “forest brothers” (representatives of the partisan movement against the Soviet government at the time). Of those deported in 1949, 183 people died on the way and 4941 more people perished during exile, which made up 12% of all deportees. Another 1,376 persons were prohibited from returning to Latvia after their deportation period expired.

A deportation train at the railway station in the town of Stende in the west of Latvia, 25 March 1949. Photo: Jānis Indriks, from the archives of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia.

Operation Priboi on the territory of Lithuania was carried out by the Soviet authorities and their local henchmen. It was the latter who pointed to the houses of “kulaks” and to families that disagreed with the policy of the Soviet government. More than 10 000 operatives and thousands of military personnel were involved in the operation in Lithuania. As a result, 33 496 people were deported from Lithuania in 1949.

The cemetery of deportees covered with sand in the Russian village of Tit-Ary, Republic of Sakha, Yakutia. Source: Museum of Occupation and Liberation Fights.

The Soviet official documents expressly confirm the deliberate nature of deportations. For instance, the outcomes of the forced resettlement from the Baltic countries in the summer of 1941 are given in the “Report of the People’s Commissar of State Security of the USSR V. M. Merkulov…” where he writes about the arrest and deportation of “an anti-Soviet criminal and socially dangerous element.” In the document titled “Memo on Losses of NKVD and NKGB during Deportation from the Baltic Republics, dated June 17, 1941” we find the word “deportation,” which is conclusive evidence that the Soviet repressive bodies were fully aware of the crime they were committing.

For nearly 50 years, the Soviet authorities silenced these atrocities in every possible way under the guise of “the fight against anti-Soviet elements.” The USSR recognized the illegality of deportations only before its collapse, in the law “On Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples” adopted by the Supreme Council of Russia on 26 April 1991. However, in 2020, Russian President Putin returned to aggressive rhetoric. In his article on the 75th anniversary of the victory over Nazi Germany, he called the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states a “legitimate annexation.”

The crimes committed by the Soviet repressive machine were not limited to deportations of people from the Baltic countries.

Soviet Deportations of Koreans

Ethnic Koreans were yet another nation that fell victim to the deportation policy of the USSR. Korean peasants, fleeing from the Japanese occupation, moved en masse to the Russian Far East at the beginning of the 20th century.

When Japanese troops invaded China on 7 July 1937, Korea was part of the Japanese Empire. The Soviet authorities suspected Korean immigrants of “aiding the enemy and espionage” and accused them of working for Japanese intelligence. Often, Russians simply couldn’t visually separate Koreans from Japanese. In addition, former citizens of the pro-Japanese state of Manchukuo (Manchurian State) and former employees of the China Eastern Railway were subjected to repressions. Everyone who the Soviet special services believed to be connected with Japan was to be arrested and deported.

Manchukuo (Manchurian State)

A puppet state under the protectorate of Japan that existed from 1932 to 1945 during the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, Northeast China.Before the start of the deportation of Koreans, the Soviet authorities adopted Resolution dated 21 August 1937, which outlined the steps to combat “Japanese espionage”. Here are some excerpts from it:

1. To propose to the Far Eastern Regional Committee (Kraykom), the regional executive committee, and Department of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs of the Far Eastern Region to resettle the entire Korean population of the border areas of the Far Eastern Region to South Kazakhstan; the area of the Aral Sea, Lake Balkhash, and the Uzbek SSR.

2. To begin the eviction immediately and finish it by 1 January 1938.

3. To allow Koreans who are to be resettled to take belongings, household equipment and domestic animals.

4. To compensate resettled persons for the value of movable and immovable property left by them, as well as crops.

5. Not to prevent resettled Koreans from going abroad if they wish and to allow a simplified border crossing procedure.

6. The NKVD is to prevent possible incidents and disturbances on the part of Koreans in connection with the eviction.

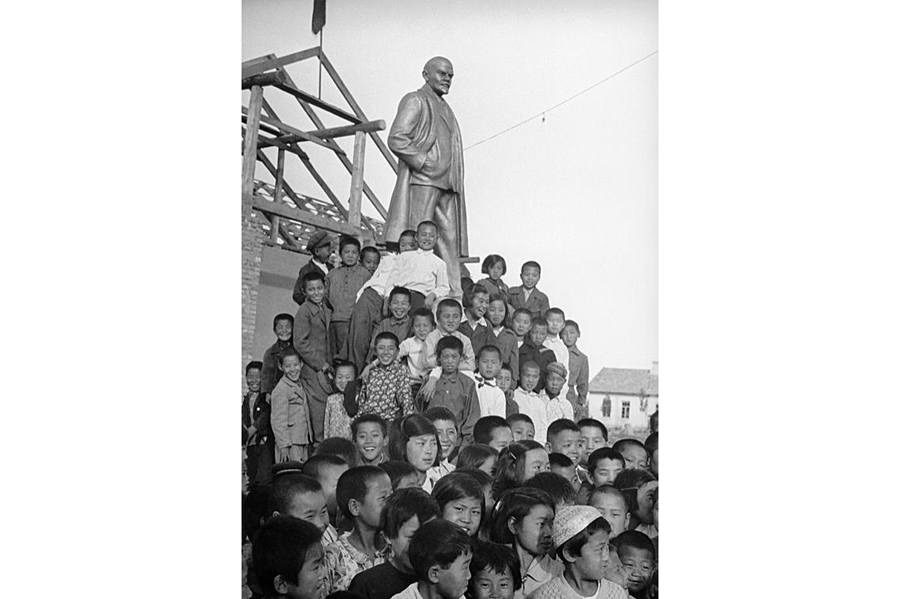

Korean children near the Lenin monument, Uzbekistan, 1930s. Photo: Max Penson.

Professor Herman Kim, a well-known researcher of deportations of Koreans during the Soviet times, describes the process of deportation in his research. According to him, ethnic Koreans were given a minimum amount of time to collect their belongings, and then they were issued individual tickets and forced to board special resettlement trains that left from a specified place at a limited time. One railway car carried 5–6 families (25–30 people). These “passenger” cars were cattle cars equipped with bunks and a burzhuika. Passports, hunting and shooting weapons were confiscated from Koreans during registration before deportation. It took 30–40 days for the train to get from the Far East to destinations in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Burzhuika

A small metal portable oven for heating rooms and cooking.It is known that 172 000 ethnic Koreans were evicted from the border regions of the Far East to the desert and uninhabited areas in Kazakhstan and Central Asia

based on the joint resolution of the Soviet People’s Committee and the Central Committee dated 21 August 1937, signed by Stalin and Molotov, the chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars in 1930–1941.

A Korean family in a rice field, 1956.

Deportation of Ukrainian Germans

Ethnic Germans settled on the territory of Ukraine in the times of Kyivan Rus and Kingdom of Galicia-Volyn (X–XII centuries). They arrived as merchants and travelers, as well as part of embassies. However, the first wave of migration was not as large as the second, which began at the end of the 18th century, during the division of the territory of modern Ukraine between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires.

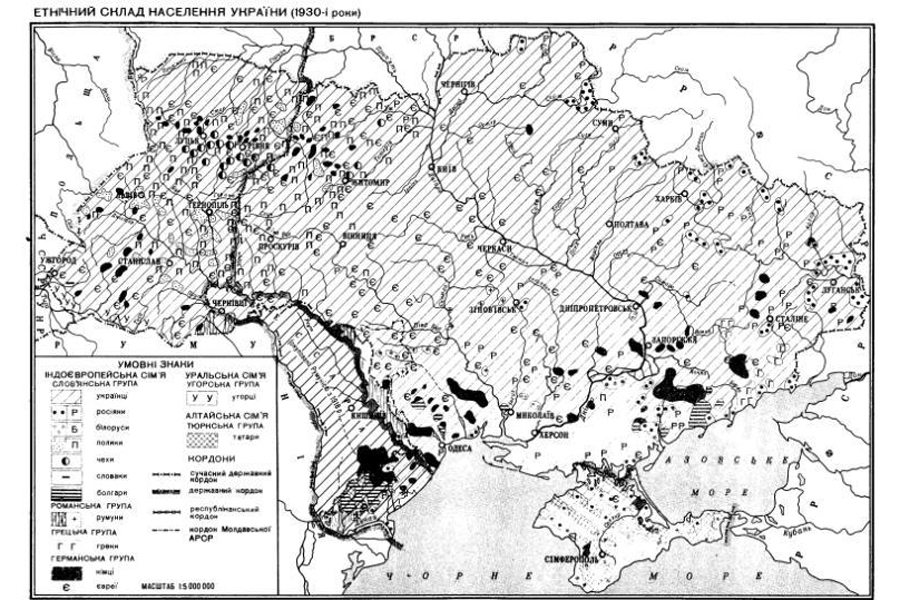

Ethnic composition of the population of Ukraine (1930s). The black colour indicates the place of residence of the Germans. Source: deportation.org.ua.

According to the 1939 census, there were 392,458 people of German nationality on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR (in particular, in the Odesa region, there were about 91,500 people, in the Mykolaiv region — 89,400, in the Zaporizhzhia region — 89,400, in Crimea — 51,300 people).

Even before the beginning of the deportations, the Soviet authorities conducted an anti-German campaign, forming the ideological basis for the future forced eviction of the German ethnic group. The beginning of such a campaign dates back to the 1920s, when with the intensification of German-Soviet trade and economic relations, German engineers and specialists began to arrive in the Soviet Union to work at industrial facilities and participate in future industrialization. Additionally, several hundred thousand Germans already lived in the German colonies on the territory of Ukraine. Andrii Savin, a researcher of the history of national and religious communities of the USSR, argues that the Soviet authorities began to consider these people as a contingent that could potentially carry out large-scale intelligence and anti-Soviet activities in favour of Germany. In his monograph called “Ethno Confession in the Soviet state. Mennonites of Siberia in the 1920s-1930s: emigration and repression. Documents and materials” he quotes the circular letter of the Joint State Political Directorate of the USSR (OGPU) “On German intelligence and the fight against it” (July 9, 1924):

“After the Treaty of Rapallo, German industry and commerce were enabled to develop their activities on the territory of our republic. From this moment, there is a massive influx of German concessionaires, industrialists, and all sorts of entrepreneurs who establish commercial and industrial enterprises, transport associations, tourist offices, and concessions.”

The escalation of anti-German sentiment gained momentum during the 1920s, and already in the 1930s, there were more radical accusations of ethnic Germans. Thus, there are known documents, in particular, “Minutes of the meeting of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in the Pulynskyi German national district,” where the Soviet communist authorities directly call ethnic Germans “fascists,” “fascist nationalist elements,” accusing them of the collapse of collective farming .

OGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate under the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR. A political intelligence service that specialised in the fight against "counter-revolution", "espionage". In 1934, it was reformed into the NKVD (People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs) of the USSR.The mass repressions of 1937–1938 became a tragic page in the history of the German ethnic group in Ukraine. In the “Ethnic Handbook“, an academic publication dedicated to the study of ethnic communities in Ukraine, the researcher Bohdan Chyrko emphasizes that in 1937, mass punitive actions were carried out against the German population of the Black Sea region (primarily the outskirts of Odesa), where about 120 thousand ethnic Germans lived, of which 50 thousand lived in three German districts — Spartakivskyi, Zeltskyi and Karl-Libknechtskyi. Based on the decision of the Odesa Regional Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks), 5,000 families of the “anti-Soviet fascist asset” were expelled from there. The main regions for resettlement of Germans were Kazakhstan, Siberia and other remote places of the Soviet Union.

One of the regions with the largest share of the German population of Ukraine was Bessarabia.

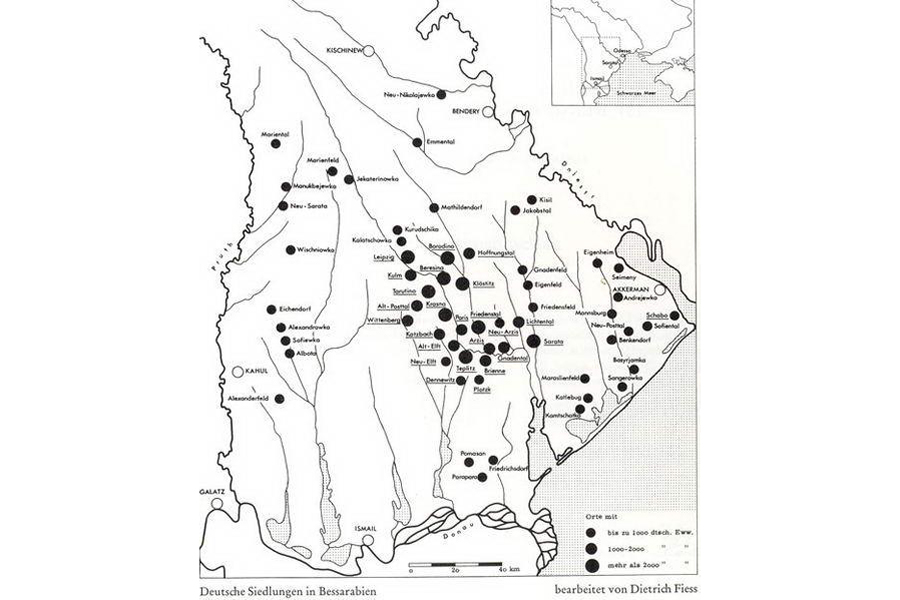

Settlements of Bessarabia, Ukraine, with a quantitative indicator of ethnic Germans. Source: frumushika.com.

In particular, there is a well-known story about the eviction of ethnic Germans from the village of Sarata (at that time it was the town). On September 15, 1940, a joint Soviet-German resettlement commission arrived there. For residents of the village, there was an official appeal published in German and Russian, which stated that all Germans aged 14 years are subject to eviction to Germany.

The relocation took place in four phases. On September 24, 1940, the first train took out the residents of the “Oleksandrivskyi shelter” (i.e., the elderly and people with disabilities), as well as part of the population from the city of Artsyz, the villages of Berezyno and Leipzig (now Serpneve). Then these people were sent to the city of Galați (Romania), later — to a refugee camp and to the German-occupied territory of Poland. Other columns of immigrants, which were formed on September 27, were taken to the city of Kiliia, which is almost 200 kilometers from the center of Odesa, and then to the refugee camp by steamboats. The last column left Sarata on October 9, 1940.

Sarata, Werner School. The last graduates of 1939–1940. Photo: Dietrich Fiess. Sarata 1822–1940.

After the outbreak of the German-Soviet War on June 22, 1941, the situation for ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union became even more complicated. In addition to previous accusations, representatives of this ethnic group in the territory of the Ukrainian SSR were accused of criminal intentions. Then the mass deportations began.

The famous researcher of deportations of ethnic Germans, Professor Alfred Eisfeld, argues that the destiny of the Germans living in the USSR was decided on August 12, 1941. On this day, the RNC of the USSR and the Central Committee of the CPSU (Bolsheviks) adopted a joint resolution “On the resettlement of the Germans of the Volga region in Kazakhstan.” Two days after that, in the directive of the General Headquarters of the Supreme Command “On the formation and tasks of the 51st Separate Army” in the Crimea, it was proposed “…to immediately clear the territory of the peninsula from residents — Germans and other anti-Soviet elements.” This directive, addressed to the Commander-in-Chief of the South-Western direction and the commanders of the units that were part of this group, launched a mass deportation of the German population of southern Ukraine on ethnic grounds. In particular, about 60 thousand Germans from Crimea were deported to the Ordzhonikidze region of Russia. And a day after the appearance of this directive, the forced displacement of Mennonites who lived on the west bank of the Dnipro in Zaporizhzhia began.

Mennonites

One of the religious Protestant communities. They appeared on the territory of the Russian Empire in the 18th century, as the tsarist government guaranteed freedom of religion, exemption from military service and provision of land for the family of a migrant.At the suggestion of the NKVD of the USSR on August 31, the resolution “On Germans living on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR” was adopted. According to this document, the authorities planned a total deportation of Germans. The decree called for the Germans, who were registered as anti-Soviet elements, to be arrested and the rest of the able-bodied male population aged 16 to 60 years to be mobilized into construction battalions and transferred to the NKVD for use in the eastern regions of the USSR. A total of 53,566 people from Zaporizhzhia, 36,205 from Stalino (now Donetsk), and 12,807 people from Voroshylovgrad (now Luhansk) regions were to be deported to Kazakhstan.

In the Altai region, the authorities were going to resettle 6,000 people from the Odesa region and 3,200 people from the Dnipropetrovsk (now Dnipro) region.

Active hostilities of the Second World War stopped the deportation of ethnic Germans for some time. A new wave of forced resettlement from the “liberated” by the Soviet army territories of Ukraine arose in 1944. Together with the communist authorities, the NKVD returned, which resumed the arrests of ethnic Germans who, under German occupation, received the special status of Volksdeutsche.

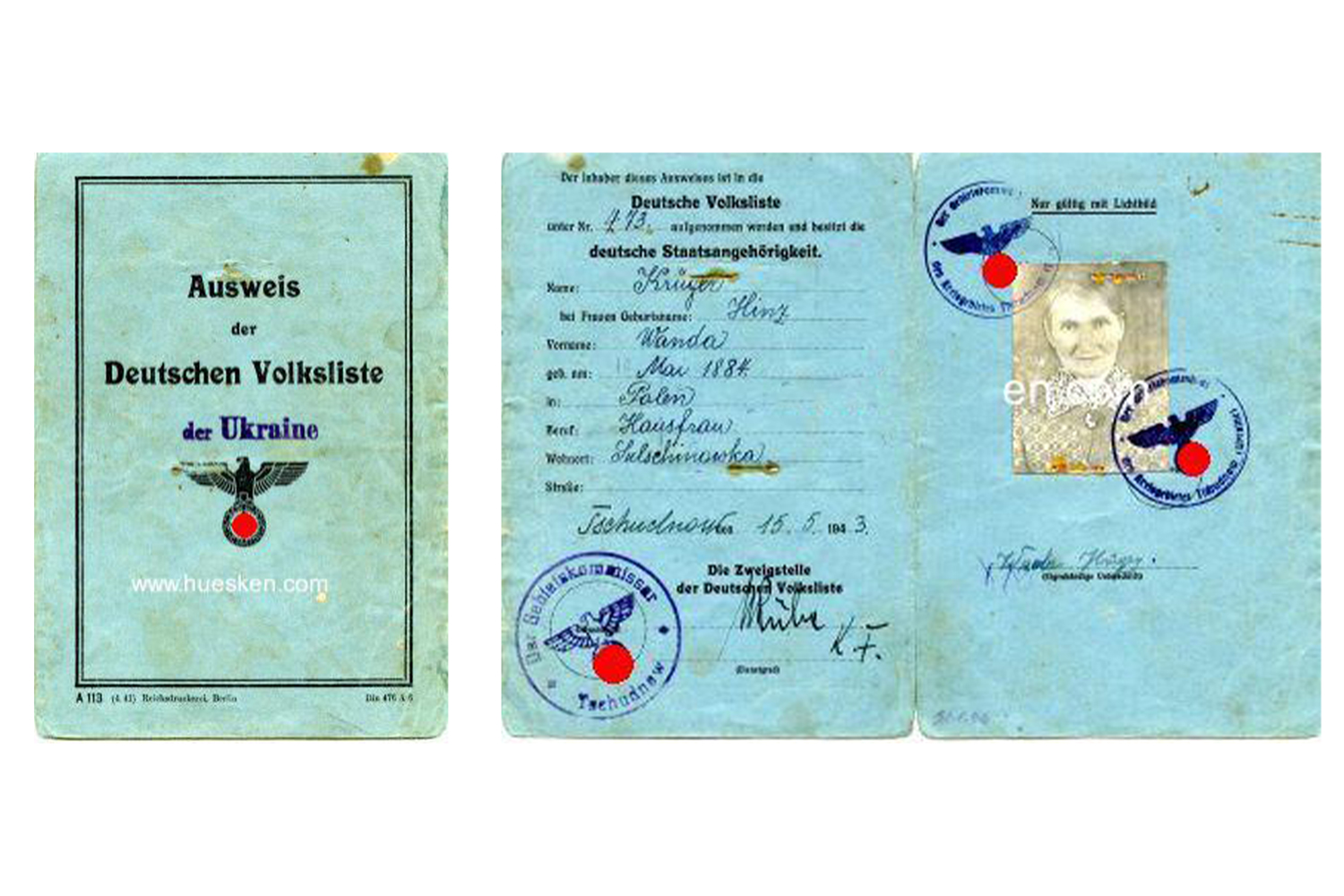

Example of certificate of a member of the German People's List of Ukraine (Volksdeutsche), issued in 1943.

On December 28, 1943, the People’s Commissar of the NKVD, Lavrentiy Beria, informed Stalin that they found 184 persons with the status of Volksdeutsche in Kyiv. In response, he ordered everyone to be arrested, kept in special concentration camps and used for work. Following this instruction, on January 7, 1944, Beria signed the NKVD Order on the arrest of citizens with the corresponding status on the territory of Ukraine. According to the decisions of the Special Meeting of the NKVD, persons enrolled in the Volksdeutsche category were sent to places of detention and exile for a period of 5 years or more, and their family members were sent to special settlements.

Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans who lived on the territory of Ukraine suffered from the deportation policy of the Union. They were transported to Central Asia and Siberia. Men from 16 to 60 years old and women from 17 to 55 years old were mobilized to labour armies and special settlements of the NKVD. Every third of them died from hunger and overwork. The regime of special settlements was abolished in 1955, and the administrative ban on returning to Ukraine — after 30 years — on January 9, 1974.

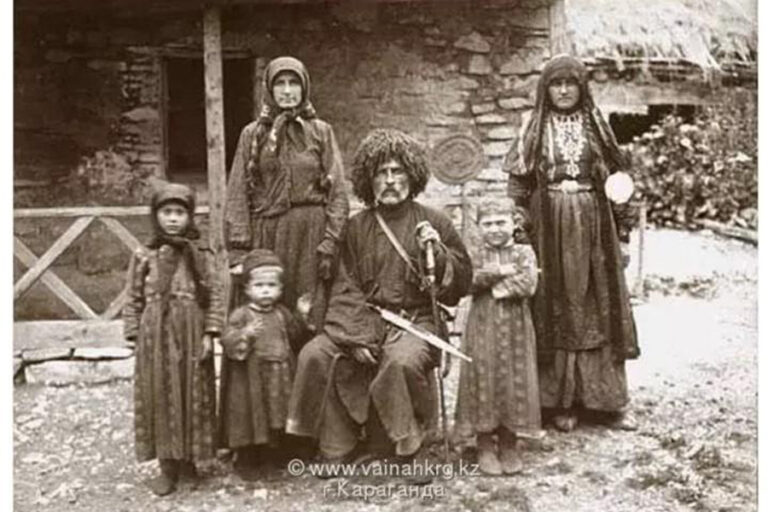

Deportation of Chechens

Paranoid suspicions of collaboration and the constant search for “enemies of the nation” and “Nazi accomplices” led to the fact that in February 1944, NKVD officers forcibly relocated about 400 thousand Chechens from the territory of the Soviet Union within eight days. They were accused of mass collaboration with the German invaders, although the Germans occupied only the area in the extreme northwest of the Chechen Republic. The prominent Chechen political scientist Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov confirmed this fact in his works. He stressed that during the military operations in the Caucasus in 1942–1944, the territory of Chechen-Ingushetia was not occupied. In his opinion, the main reasons for the persecution and destruction of the Chechen mountaineers are as follows:

– Chechen and other highlanders of the Caucasus constantly fought for their independence and therefore did not recognize the despotic system of the Soviet colonial regime;

– Moscow’s desire to make the Caucasus the rear of the Soviet metropolis and to prevent the Western influence on the Caucasians;

– Striving to make the Caucasus a reliable base for the future expansion to Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and India.

Operation "Lentils", in which Chechens and Ingush were deported. Author of the map: Tahirgeran Umar.

The documents around the forced deportations of Chechens and Ingush stated that in connection with the eviction, it was necessary to abolish the autonomy of the Chechen-Ingush Republic. At the same time, its four districts were transferred to the Dagestan ASSR, and the rest became the Grozny region. Meanwhile, the local population was deported to Central Asia and Kazakhstan “for aiding the fascist invaders.”

The eviction process in most areas (except for highland settlements) began on 23 February 1944 at 5 am. 180 echelons with 493,269 people were sent away. On the way to the destination, which sometimes lasted more than 20 days, 56 babies were born, 1,272 people died, and 285 were sent to medical institutions. Stalin personally supervised the eviction of the Chechens and Ingush. In Beria’s telegram to Stalin of 1 March 1944, he reported the successful completion of the forced resettlement of more than 400,000 people.

The testimony of eyewitnesses about these tragic events has been preserved. Here is what Zalva Musayeva, sent from the village of Stari Atagi of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR, recalls:

— People all were gathered, and began to be taken out of the village. Three soldiers came to us and asked if there were any adults. I said that I was waiting for my mother and brother; they worked in Grozny at a military factory. The military said that they were not worth waiting for; they would not come and began to help me collect something, offering to take some food and warm clothes. Among the products was corn flour, among warm things — my mother’s coat and an old father’s jacket. I insisted and took the Zinger sewing machine; it helped to survive in Kazakhstan. We arrived by some vehicle (pulled by horses or oxen carts. — ed.) to Grozny. I was hoping to meet my family there — my mother and brother. 10-15 families were put in a freight car, and each Chechen family had 6-7 children…

slideshow

The Second Amendment, adopted by the plenary Assembly of the European Parliament on February 26, 2004, states that based on the IV Hague Convention of 1907 and the Convention on the Prevention of the Crime of Genocide of 1948, the deportation of all Chechen people was an act of genocide.

Deportation of Crimean Tatars

The main population of the Crimean Peninsula, the Crimean Tatars, also underwent mass deportations by the Soviet authorities. The Communist Party claimed to have the following reasons for this:

● desertion of the Crimean Tatars from the Soviet army,

● collaboration with the Nazi occupation authorities of Crimea in 1941–1944,

● military service in units cooperating with the German army during the German-Soviet War.

In reality, many Crimean Tatars fought against the Germans as part of the Soviet army. Some even received state awards from the USSR. For example, the pilot, Amet-Khan Sultan, was twice awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Therefore, the accusations of the Soviet authorities of desertion and collaborationism were false and manipulative.

Mustafa Dzhemilev, the leader of the Crimean Tatar people’s movement and the Presidential Commissioner for the Crimean Tatar people, argued that there is an eternal intransigence between the Crimean Tatars and the Soviet (Russian) authorities, for whom the Second World War was the reason for the final “cleansing” of the Crimea from its indigenous people.

On 11 May 1944, a decision was made to evict the Crimean Tatars to the Uzbek SSR. To implement this plan, the Soviet government prepared cautiously. In addition to the ideological justification, it attracted a considerable power resource: 5,000 operatives of the NKVD and the NKGB of the USSR arrived in Crimea, while 20,000 soldiers and officers of the internal troops of the NKVD were involved in a secret operation. According to other sources, up to 32,000 NKVD and other law enforcement officers were involved.

The violent eviction of the Crimean Tatars began on 18 May 1944, and in some settlements of the peninsula — on the evening of 17 May. Historian Oleksandr Pahiria cites the following testimony of eyewitness Dilyaver Ennanov:

— Suddenly, a loud roar at the door in the middle of the night. When I woke up, I saw an officer reading something on paper angrily to my mother. There were two soldiers next to him. The officer hurried. He said there were 10 minutes to go. <> We were taken from the house to the courtyard. Our neighbors, also Crimean Tatars, sat with their staff in the rain, surrounded by soldiers of the internal troops. We stayed with them until dawn. [The military] drove the cars and took us to the end of the city, to the railway station. <> I remember we were put in a double carriage, No. 44. The train departed with tears, moaning, and screaming. When crossing the border of Crimea, everyone who was in the echelon sang a song. We were singing and crying and looking back.

Beria reported to Stalin and Molotov at the beginning of the operation to deport the Crimean Tatars on May 18, 1944. And on the same day, 90,000 people were prepared for forced resettlement, and 48,000 of them were sent to the east in echelons. The next day, 165,000 people of the “special contingent” gathered from the territory of the entire peninsula, and 136,412 of them were deported, notes historian Oleksandr Pahiria.

On 20 May 1944, Deputy People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR Ivan Sierov and Deputy People’s Commissar of State Security of the USSR Bohdan Kobulov summed up the results of the three-day operation in a report to the supreme party-state leadership: the deportation of the Crimean Tatars was completed at 4 pm, according to its effects, 180,000 people were resettled — the punitive authorities sent more than 70 railway trains from the peninsula, each having 50 carriages full of the displaced people.

As for the number of deportees, the statistics vary, but it was at least 200,000 people: 183,000 were sent to a special settlement, 6,000 to reserve camps, 6,000 to the Gulag, and 5,000 to the so-called special contingent to the Moscow Coal Trust. According to the National Movement of Crimean Tatars, this figure may be twice as high — 423,100 people.

The Soviets banned the Crimeans from returning to the peninsula: in 1948, the Soviet authorities declared them “life-long” immigrants. Crimean Tatars still tried to return and staged demonstrations in the 1950s-1960s in Moscow, but the ban on return was in force until 1989.

slideshow

After the occupation of Crimea in 2014, the Crimean Tatars are again experiencing repression. Russian law enforcers and FSB officers conduct constant searches, call Crimean Tatars Muslim terrorists, persecute and intimidate activists. They are imprisoned and sometimes disappear without a trace of the published disapproval of the occupation regime.

The Russian occupation authorities carefully constructed the narratives they needed, trying to erase the collective memory, in particular about the three occupations of Crimea (the first — back in 1783, when the Russian Empire annexed the Crimean Khanate) and two waves of deportations. It also banned the traditional commemoration of the anniversaries of Stalin’s deportations of the Crimean Tatars.

Undoubtedly, the mass forced eviction of an entire ethnic group and the subsequent impossibility of returning the survivors to their native lands is the genocide of the Crimean Tatar people, initiated and embodied by the Soviet authorities.

Modern deportations of Ukrainians to Russia and Belarus

History should encourage humanity to draw conclusions. Contemporary scholars have viewed deportations as archaism, one of the repressive mechanisms of totalitarian regimes that would never happen again. However, the policy of the Russian Federation, especially during the reign of Putin, shows the opposite.

The deportation of Ukraine’s civilian population from the temporarily occupied territories and their forced integration into Russia is a planned policy of the aggressor country.

Deportation train from the city of Luhansk to the Russian city of Gukovo.

Prior to February 24, 2022, information about the initial instances of these deportations emerged: in the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (DPR/LPR), the Russian authorities organized “evacuation trains” by which Ukrainians were taken to the Russian Federation. On February 19, 2022 alone, more than 13,000 people were deported in this way. The train went from the city of Luhansk to the town of Gukovo (Rostov region of the Russian Federation). According to the Russian data, as of February 21, 2022, more than 60,000 Ukrainians were taken to the territory of the Russian Federation from pseudo-republics in the east of Ukraine.

To accommodate deportees from Ukraine on the territory of the Russian Federation, invaders created the so-called places of temporary accommodation. In fact, they are the camps where Ukrainians are detained since they have no opportunity to return to the territory controlled by Ukraine. The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) also participates in this process under the patronage of the Department of Charity and Social Service of the ROC on the territory of monasteries, charitable institutions, and church orphanages, disguising it as assistance to the “Orthodox brotherly” people in “saving” them from the full-scale war they launched. For example, the official website of the Russian Orthodox Church contains information about the headquarters of church assistance to “refugees” in Moscow, where more than 29,000 Ukrainians were registered from March to December 2022.

Temporary accommodation in the territory of the Russian Federation, created by the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). Source: slidstvo.info.

In the publication from February 28, 2022, they mention the sports and recreation complex “Romashka,” located in the Neklinovsky district of the Rostov region. In particular, they posted about the visit of the Metropolitan Mercury of Rostov to this institution and about 500 children who were there as “evacuees” from two boarding schools and a social rehabilitation center in the Donetsk region.

Currently, the exact number of deported Ukrainians has not been established. However, according to various sources, it varies from 2.5 million to 4.5 million people. On 16 January 2023, the analytical report of the Coalition “Ukraine. 5 a.m.”, announced the potential number of Ukrainians who suffered from Russian deportation, from 2.8 to 4.7 million people.

Ukrainian children, unfortunately, suffer from Russia’s crimes too. In particular, they become the victims of deportations. According to the analytical report of the Coalition “Ukraine. 5 a.m.”, the occupiers forcibly relocated from 260 thousand to 700 thousand Ukrainian minors. The website “Children of War” indicates the deportation of 738 thousand children. This data comes from the National Information Bureau, based on information from open Russian sources. About 20,000 children who were deported from the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine from 24 February 2022 to 18 May 2023 have been identified.

Deported people from Mariupol to Vladivostok, photo by RosMedia. Source: Ukrainska Pravda.

The main goals pursued by the Russian occupiers in committing this crime are as follows:

– The deportation of Ukrainian children to “re-educate” them, destroying their Ukrainian identity

– Illegal adoption of children and granting them Russian citizenship to solve the negative demographic situation on the territory of the Russian Federation

– Raising abducted children in line with Russian propaganda and forced militarization by engaging in paramilitary structures such as “Yunarmiya” (from Russian — “Young Army”) to raise the future generation to commit new acts of armed aggression against Ukraine.

All children in Ukraine’s temporarily occupied territories are at risk of being forcibly deported. This is the story of Yevhen Mezhevyi, a father of three children from Mariupol. After the city’s occupation, the Russian military conducted “purges” of the local population. Yevhen’s family was taken from Mariupol to Bezymenne village, one of the main filtration centers in the occupied Donetsk region. The children were taken from their father, who was imprisoned for no reason. Neither the children nor Yevhen knew about each other’s location. After 45 days in prison, Yevhen was released on May 26, 2022. At that moment, his children were already taken to the Polyany Boarding House, Moscow region. Assisted by volunteers, Yevhen successfully reached the capital of the Russian Federation and retrieved the children, narrowly averting their unlawful adoption. Now, the family lives in Latvia, but this is one of the few cases where the children were saved, although the grandmother is still in Russian captivity. Most deported children, even those with parents, are still being held by Russians. It is extremely difficult to find out the whereabouts of Ukrainian minors and, even more so, to return them to their homeland.

Yevhen Mezhevyi with children. Source: Ukrainska Pravda.

What to say about children, even if it is difficult for adults to protect themselves from being forcibly deported, and especially if such action is hidden. “We have already come to terms with the fact that we are being taken to the Far East,” recalls Anna (the surname is not indicated for security reasons), a resident of Mariupol, who was forced to flee with her relatives from the city, which the Russian military deliberately erased from the ground. The audio conversation with the woman was handed over to us by the PR Army team, which collected similar facts of Russian crimes for the archive.

Anna was accompanied by her 70-year-old mother, who had limited mobility due to an injury, and her 27-year-old son with a disability (specifically, an autoimmune spectrum disorder) who had been affected by a blast wave during one of the attacks while walking over water. Due to the escalating crisis in their hometown, the need to escape became critical. On April 4, 2022, they departed Mariupol on foot, with minimal belongings and financial resources, but fortunately, they carried some essential documents.

According to Anna, at one of the improvised enemy fortifications, the military from the DPR informed them that in Mangush, located approximately 20 km from Mariupol, they had the freedom to travel anywhere, whether it be Ukraine or Russia. However, the family chose to head towards Melekino because Mangush was located on the opposite side, and they would not have been able to reach it without a car. Fortunately, Anna and her family successfully reached their destination. Anna recalls that she required urgent medical attention, so they agreed to enter the territory of the Russian Federation based on the assurance that they would not be subjected to any form of scrutiny. The following are Anna’s recollections after they were transported from Melekino to Volodarsk in the Donetsk region.

— Eight large buses arrived, each capable of carrying 50 people. We inquired with the driver about their origin, and he responded, “We’re from Khakassia.” Interestingly, the volunteers who were present were not locals either. They were identifiable by their red T-shirts bearing the words “United Russia.” In the subsequent camp we were taken to, both in Taganrog and Tikhvin (Russian cities), all the volunteers were affiliated with United Russia. They organized the people and addressed inquiries. <> Each bus had an armed soldier, a camouflaged individual carrying a rifle, and two drivers. They informed us that they would transport us to Novoazovsk, which is now part of the occupied Donetsk region, and that the journey would take two hours. However, in reality, we traveled for twelve hours.

The woman further highlights that around 700-800 individuals, including 200 children, from Mariupol successfully reached Taganrog. They were not informed of their destination. Anna emphasizes that their movements appeared to be carefully planned and well-coordinated. Despite enduring a long and grueling journey with inhumane treatment, such as a lack of medical care and water, the Russians exploited them for their own purposes.

“We began to disembark from the train, and the whole event was organized and televised in Russia. The narrative portrayed us as Mariupol residents who had escaped the clutches of the Nazis. Supposedly, we were to be warmly welcomed, provided with food, warmth, and our needs taken care of,” Anna recalls.

She adds that unfortunately, some individuals fell for this “warm welcome” due to intimidation and extreme emotional and physical exhaustion. The lack of information and communication added to their disadvantage. Both in Mariupol during the evacuation and within the aggressor country, there was no mobile communication available. These circumstances made Ukrainians susceptible to the manipulations of the enemy.

Anna and her family initially intended to travel from Russia to Finland, but eventually, they managed to leave for Estonia.

Deported children from Donetsk region as part of the "Youth Army", Volgograd region of the Russian Federation.

The facts of forced removal of orphans and those who are deprived of parental care from the territories occupied by Russia have been documented. The stories of eyewitnesses are collected, in particular, by the Where are our people project team, which investigates the deportations of Ukrainians and the ways of their return. Indicative and tragic is the story of Volodymyr from Kherson, who was the director of the Center for Social and Psychological Rehabilitation of Children. After the occupation of the city by Russian troops, the man took custody of 50 orphans aged 4 to 15 years. Enemy missiles and projectiles regularly flew past the orphanage. Children could walk in the yard for no more than fifteen minutes, Volodymyr asked them not to leave the building, and the orphanage teachers even had to hide all the wards because the invaders hunted them to take them to Russia. Volodymyr guarded the orphans for months, until once again Russian soldiers took away the documents because they could not find the pupils. Staying in the orphanage became dangerous, so Volodymyr transferred the children to the church building, where they had to sleep on mattresses. Unfortunately, the Russian military eventually found them and took them away. The orphan was deported first to the occupied Crimea, and then to the Russian city of Anapa (Krasnodar Territory, Russia). After long negotiations and extraordinary efforts of the Ukrainian authorities, Russia agreed to return the children through Georgia to Ukraine in a safe zone.

The Russians are actively engaged in ideological and propaganda manipulation of deported children. In particular, they create special camps for children, designing them for the so-called “adaptation and assistance in the fight against post-traumatic syndrome.”

Ukrainian children are forcibly militarized, forced to write letters and draw postcards to the Russian military, who bomb their homeland.

Such actions of the Russian occupiers against Ukrainian children are a violation of a number of articles of the Geneva Convention (Articles 3, 17, 55, etc.) and its Additional Protocol (Articles 51, 78), Article 21 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 283 of the Family Code of Ukraine, which gives grounds to assert that modern Russia is a terrorist state.

Children abducted by Russians in Izium.

This is not the first time that the Russian Federation has committed crimes against humanity. It deliberately repeats and scales of the mass repressions committed by the Soviet Union, whose legal successor it became. At that time, during the communist dictatorship, about 6 million people were deported. From February 24, 2022, to May 2023, Russia deported at least 2.8 million Ukrainians, and this is only data obtained from open sources. Probably, we will learn many more terrible facts after the victory because the terrorist country has been practicing for decades in covering up the traces of its crimes. Currently, many deported Ukrainians either do not have the opportunity to tell about their experience, or are afraid to do so, feeling a threat to their lives or the lives of close ones.

Russia’s goals have long been known — to destroy the Ukrainian people and erase its history. However, more than a year of full-scale war shows convincingly that Russia, unlike the Soviet Union, will not be able to escape responsibility for its crimes. The already documented facts of Russian crimes and those that Ukraine will still have to uncover will serve as irrefutable evidence to hold the guilty accountable. After all, Ukraine is supported by so many democratic countries that Russia will not be able to pull off the USSR’s trick and cover up such large-scale crimes against humanity. For example, on March 16, 2023, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin and Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova because it was they who gave orders to forcibly deport Ukrainians, the illegal removal of children and their adoption by Russian families. The very recognition by the international institution of the actions of the Russian authorities as crimes against humanity can be the first step towards punishing Russia for centuries of deportations.