Marharyta and Roman Martynov have turned their family hobby — making their own sauces for homemade dumplings or borshch — into a successful business. In the town of Zhovti Vody, the couple and their parents have set up a production line, making berry-based, tomato-based, and spicy sauces. They come up with their own recipes, and source their vegetables and other ingredients from farmers they know and trust.

Until recently, despite the variety and availability of fruits and vegetables, the only popular condiments in Ukraine were ketchup, mayonnaise, mustard, and horseradish sauce. Slowly but surely, artisan manufacturers are changing this state of affairs. Artisanal sauces are produced in relatively small quantities, at low production capacity. Unlike factory-made sauces, artisanal ones are made manually. The makers experiment with flavours, original recipes, and unusual combinations of ingredients.

The Ukrainian artisan sauce market has been developing since 2013-2014, when demand for domestic goods rose. Among the popular brands is Mr. Caramba, famous for its spicy pepper sauces as well as its berry concoctions (for example, cherry and garlic, or cranberry and red wine). In Mr. Caramba’s six years of activity, its products have reached the shelves of chain stores: their sauces are stocked by the supermarket chain Silpo under the label ‘Lavka Tradytsii’ (‘Store of Traditions’ — tr.), which also supports this series of stories on local farmers.

“Just another of Ryta’s ideas”

Marharyta and Roman Martynov make their all-natural Mr. Caramba sauces with their parents. They started out with their parents’ preserves, followed by experiments and unexpected combinations of ingredients. In 2020, they launched the production of thirteen varieties of sauce in Zhovti Vody.

When Marharyta went on maternity leave, doing nothing was out of the question: she wanted to earn money. She decided she had to come up with an idea that was close to home:

— My parents always cooked a lot: they made delicious food that many people considered quite unusual. So we decided to expand the circle of consumption of their homemade products. At first nobody took me seriously — “Just another of Ryta’s ideas…”, they said. Because before this, I used to sell things from China. My husband and I also made a starry sky that glowed at night. Basically, I was constantly coming up with ideas.

Roman explains that in 2013-2014 there were no other products like theirs on the market. Nothing but mayonnaise and ketchup. What’s more, there was a gap in the market for spicy sauces:

— At that time everyone was making jam. It was Zhenia Klopotenko (Ukrainian culinary expert and chef — ed.) who started it. The ‘Confiture’ gastronomic workshop started up. Then, for some reason, everyone decided to follow Zhenia’s idea, and a lot of homemade jam manufacturers emerged. We moved into another area. We realised that making jam wasn’t the only thing you could do with berries: you could make sauces too.

In 2014, the family began making their first sauces to sell, and participating in themed festivals. At Kyiv Food Market they got an enthusiastic reaction. The couple rejoiced. Previously their parents had been sceptical that the idea would catch on, but that was the moment when their parents’ prejudices were shattered.

The Family

Roman’s parents grow garlic, mint, and dill for the business. Ryta’s parents, Oleksii and Tetiana Shpin, are on the production line, and her sister Seraphyma does the drawings for the labels. She developed the first design at the age of 16, using a gel pen to draw each sticker on every jar by hand. Now the labels are printed, but the design has not changed. Roman says that customers often recognise their products by Seraphyma’s drawings alone.

— Actually, they have the same characters, the same design and style. Now they’re fully in colour. They’re just pictures of people. One is a Mexican who loves hot peppers. This gives each sauce its own particular feel, associating it with an image.

Marharyta says there are numerous advantages of working in a team like this:

— We are confident that high-quality production can be sustained over the years. It doesn’t matter how many jars we produce. Because we trust the people we work with, because they’re our parents, and everything — every pepper, every tomato — passes through their hands.

slideshow

Every member of the team has specific responsibilities that they have mastered with practice. No one in the family has any previous experience in gastronomy.

— It’s a new science for all of us. As Roma says, it’s like we’ve all done an extra university degree. We’ve made mistakes on a huge number of steps, spent a lot of time and money on things we now realise were unnecessary. But this is our experience, and we paid for it with our mistakes.

Despite everything, they sometimes have trouble reaching an agreement. Roman recognises that on this level it is easier to work with an employee, because you can be more direct. If you work with your family, you have to choose your words wisely so as not to offend anyone.

Marharyta’s father, Oleksii, says it can be difficult to work with his daughter because different generations have different tastes. And they need to please everyone.

The family business has hired only one external employee — Mykola.

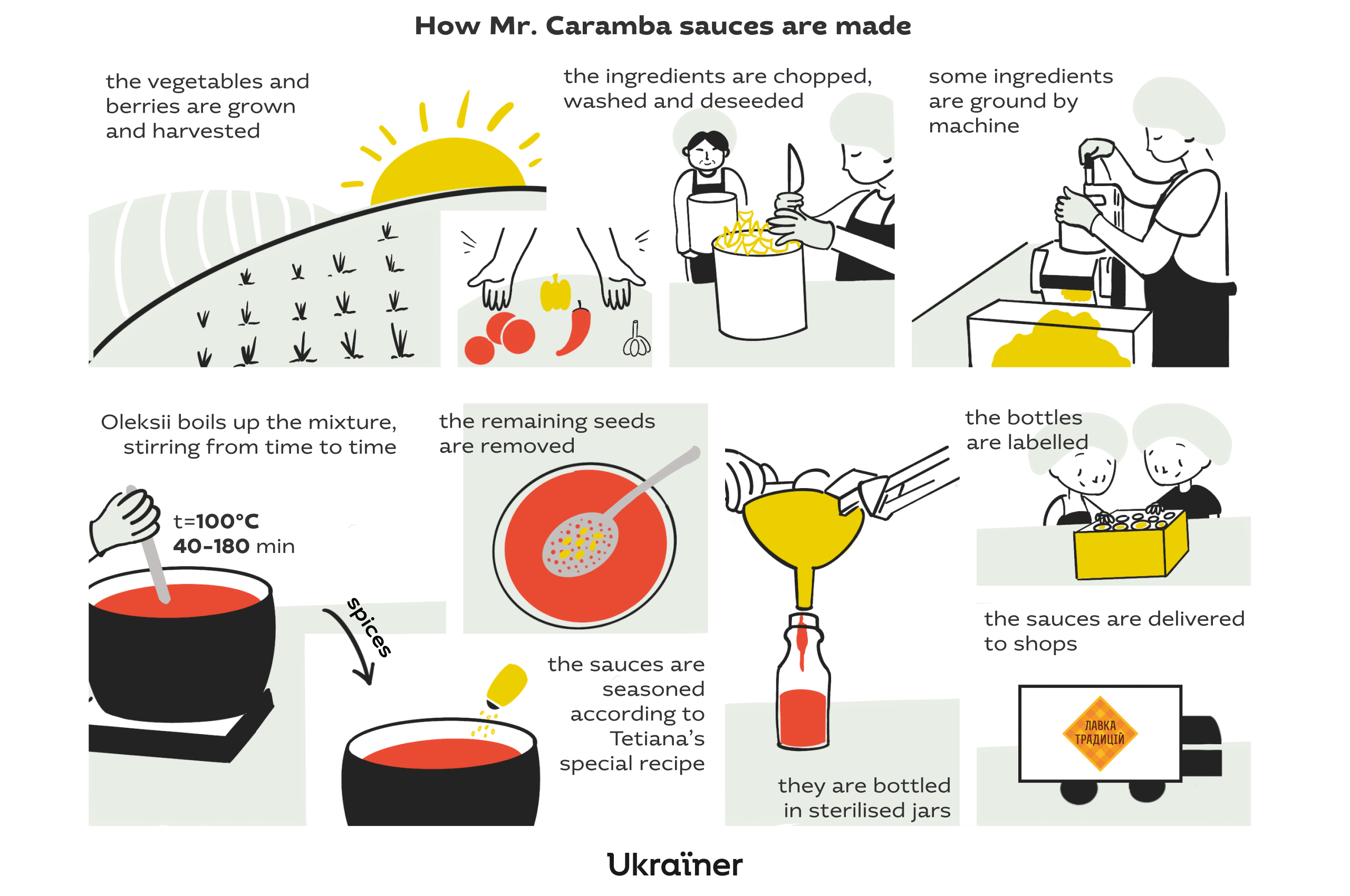

How the sauces are made

According to Roman, developing a sauce recipe is a real science.

— It’s like simultaneously writing your coursework or thesis at every faculty of the university. We have to understand what the customer needs, even on a subconscious level. Ryta and her parents decide what the taste contrasts should be, and where to add special flavour notes.

New recipes for sauces are born from Marharyta’s experiments. If it doesn’t work out the first time round, she asks her father for help. Sometimes Marharyta gets nervous. For example, when developing their recipe for smoky barbecue sauce, several attempts were required.

— Although we’d been considering a lot of great options for our barbecue sauce, the difficulty was to choose the best from a range of decent ones.

The family considers ‘Smoky Barbecue’ to be their hit: all their hard work paid off. The Martynovs had been trying to make a high-quality barbecue sauce without using liquid smoke. As Marharyta recalls, she and her mother must have tasted all the barbecue sauces in Ukraine to gain an understanding of its finer points. Then they began smoking peppers themselves.

— Our goal was to make a cool, delicious, high-quality sauce, whatever the cost. We didn’t want to make a cheap one. So it’s expensive to produce, but when people taste it, they realise why this sauce is twice as expensive as the others. It takes two days to make, and the ingredients are far from basic.

When the family is deciding whether to start production of a sauce, they organise tastings to test it out — in other words, customers are involved straightaway. Roman explains that they need to listen to people’s advice: add more salt, make it hotter, or vice versa.

— But there were times when we started producing a particular sauce that everyone had enjoyed. It went out on the shelves, but nobody bought it because we simply hadn’t chosen the right name. We had ‘Peach-Habanero’, but most people didn’t know what ‘habanero’ was (a variety of hot pepper — ed.). They thought they were buying peach sauce, then got upset with us because it was too hot. So our experiments do fail sometimes.

The head of the workshop is Marharyta’s dad, Oleksii, who is responsible for all the sauces and cooking processes. He knows exactly what to buy, and how much. Mum Tetiana is in charge of the inventory and accounts: she has a head for numbers and accuracy.

The production process is divided into several stages. First, we get a delivery of fresh vegetables: for example, 400 kilos of peppers. These are cut, then washed, so fewer seeds end up in the sauce. After that, all the ingredients and spices are put into a pan and boiled. It gets very hot in the workshop.

Marharyta says the family always has Mr. Caramba sauces in their fridge at home.

— The vegetables that go into our sauces are the same ones we use ourselves, because we are the primary consumers of our products.

They add fresh and dried ginger to some sauces, like ‘Gentle Chili’. The fresh ginger enhances the taste, while the dried ginger adds to the aroma. The ginger they use is purchased at the market.

Then the bottling process begins. First they sterilise the glass jars, each of which has a capacity of 300 grams. Roman worries that the sauce might not look appealing because of the seeds.

— We do get chilli seeds in the product, which are dry and black. There’s nothing bad about it, but it doesn’t look quite right. That’s why one of the last steps in the process is to use a spoon to pick out all the small seeds you might get in a batch. Our sauce looks great through the glass, and we want everything to be perfect.

Marharyta says that as of summer 2020, the family’s output stands at 3,000 to 3,500 jars a month. The business is gradually developing. Roman shares his plans for establishing a bottling line.

— We can’t afford it yet. We’re more in need of a machine that chops vegetables. We’re developing our business without relying on other people’s money. Of course, we’ve been paying modest salaries to ourselves, but all the rest, all our earnings, we’ve invested back into equipment.

slideshow

The last stage, before the sauces are sent out for sale, is labelling. The family has invested in a device that takes care of this process.

— On the jars we have to indicate the sauce’s exact ingredients and the date and location of manufacture. Plus the caloric value, our details, and the barcode. We also have something called a ‘heat scale’. We thought of that ourselves. When you’re choosing a sauce, you need some indication of how hot it is. Sima’s also made an infographic for the label that shows what dishes you can add it to. Well, that’s very subjective. For example, the label might say it goes with salads, fish and chicken, and I might eat that sauce with borshch, but I don’t tell anyone about that.

Ryta specifies that their total output is divided into three categories: berry-based, tomato-based, and pepper-based. The range has been reduced from over twenty sauces to thirteen.

— We have the most popular ones — let’s call them the top six sauces. There are seasonal sauces, like ‘Hostra Pasta’ (Hot Paste — tr.). We made 300 small jars of habanero sauce. It ran out in the winter, so we stopped selling it until the next pepper harvest. The sauce gets bought up by fans, all of whom I know by name. When they ask if it will be available again soon, I tell them we need to wait until the new crop is ready.

The couple claim that they never intended to make any sauce at a cheaper price.

— We don’t sell our sauces just to make money. It’s also about the whole family participating, to manufacture a product that’s no worse than anything made by a foreign manufacturer. Ukrainians often believe that Italian or French sauces must be much better than ours. But why is that? Is it our inferiority syndrome? Our cheese makers are already receiving awards in Lithuania and France for their cheeses. So there is every reason to be proud of our fellow Ukrainians. Even if the product is expensive. Because I believe quality doesn’t come cheap. Because if you take high-quality products, then you cannot sell them at less than the cost price.

In the field

When the Martynovs were producing 30-50 jars of sauce per month, they attempted to grow all the vegetables themselves. When the output reached over a thousand jars, they started buying raw materials from local farmers. The family has already established a network of farmers, from whom they regularly order vegetables or berries.

In the village of Iskrivka, 20 km from Zhovti Vody, farmer Volodymyr Put grows vegetables for the Martynovs. He and Roman met online; only recently have they met in person. Roman says he trusted the recommendations and they started working together.

— We have a simple requirement for our product: everything should be honest, without banned substances. We want our vegetables to be grown the way they should grow, in the soil.

slideshow

Volodymyr begins to grow seedlings in February, and plants them out in May. For irrigation he only uses water from the nearby Balka River. Now, in the summer of 2020, he has seven thousand bushes, from which he expects to harvest three tons.

The soil is fertilised with organic matter, and the vegetables are protected from pests by other insects.

— This year I didn’t spray (the crops — ed.) with anything at all. There were a lot of ladybirds on the peppers. And they eat aphids, so God was kind to us. That’s how it was last year, and that’s how it is now. Ladybirds are great helpers, the perfect way to get rid of aphids. We don’t have any slugs. We did have some trouble when we were growing habanero peppers: then we left beer out for them, and they crawled right in. At night we went out with torches to collect them by hand.

The seeds from the best and largest peppers will be collected to be sown next year — although when it comes to peppers, Roman says the most important thing is the heat.

Sale

Initially, they began to sell their sauces in health food stores. However, this decision did not prove to be successful.

— We didn’t get our target audience right. We really hoped we’d got a lucky ticket. In fact, our audience can be found in butchers’ shops.

Mr. Caramba’s first partnership was with ‘Miastoria’ (‘Meatstory’ — tr.). Later, they joined up with ‘Rizhky i nizhky’ (‘Horns and Legs’ — tr.), ‘Miasnyi Rai’ (‘Meat Heaven’ — tr.), ‘Tibon’ steak shop, ‘Miasoid’ (‘Carnivore’ — tr.), and ‘Silpo’.

Their sauces can also be purchased online. Roman says that if he had acquired the knowledge he has now, but five years ago, he would have reached the current level of development at a much faster rate.

— Five years on, we, the producers, have come to understand that we should only be focusing on production. For the sales side, there are shops and other platforms. Of course we have a website and we’re on social media. We can even remind people about ourselves once a month, but we don’t invest a lot of resources in that. We just have a website, an opportunity for anyone from any part of Ukraine to order our sauces.

Sometimes families say that the products are too expensive. However, though a jar of sauce can cost over 100 hryvnia, people still buy them.

Marharyta says her family is always willing to share experiences. Criticism is not taken as an insult.

— Constructive criticism allows us to work on our mistakes. As Roma says, if you make some adjustments here and there, you’ll get to the next level. You might even see your business in a different way.

In the next five to ten years, the business will expand, as will the workshop. Roman says they have a good idea of where the business is going. Marharyta claims they will need to devote all their energy to developing the brand.

— Mr. Caramba is like an extra child: it needs attention, progress, study, and growth. And we’re responsible for it, just as if it were a family member or a child.

supported by

This series about local farmers is supported by ‘Lavka Tradytsii’