From ancient times to the present, the Ukrainian church has faced numerous challenges. Its history may seem complex and convoluted, having been under the shadow of the Russian empire and later Soviet occupation since the late 17th century.

Throughout these periods, Ukrainians and other national communities in Ukrainian territory were denied freedom of religion, self-expression, and cultural identity under imperial and communist rule. The Kyivan Church, the region’s oldest, suffered persecution and Russification. It was only with the declaration of Ukrainian independence in 1991 that the Ukrainian church began its revival. This period saw the coexistence of the revitalised Ukrainian church with the Russian church, which had been forcibly imposed and represented as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (essentially the Russian Orthodox Church).

Does Ukraine really ban Christianity and the church?

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, government and civil society representatives began working to eliminate Russian influence in various aspects of life, including religious institutions. Meanwhile, the Kremlin and the Russian Orthodox Church have constructed an extensive propaganda machine based on decades of dominating the religious environment of Orthodox Christians worldwide.

They are attempting to persuade the world that Ukraine “bans Christianity” and “persecutes believers”. This false narrative is particularly promoted by US presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, who claims that Ukraine is “using American taxpayer money to ban Christianity.”

What exactly is going on? The Verkhovna Rada (Parliament — ed.) of Ukraine has banned the activities of religious organisations with ties to the Russian Federation as part of Ukraine’s national security efforts during the war. The essence is as follows: if a church institution is proven to be connected to the aggressor state (Russia is officially recognised as such), its operations in Ukraine can be terminated through legal proceedings.

The law does not entail restricting anyone’s right to religion. A lawsuit against individual church representatives or institutions should not be construed as a ban on the church or religion as a whole. Instead, it is a matter concerning national security and the violation of Ukrainian law. Some members of the Ukrainian Church Moscow Patriarchate are currently facing charges of treason, which are among the most severe in any country’s legal system.

Military chaplains of Ukraine

According to the United States State Department’s annual International Religious Freedom Report, 62.7% of Ukrainians identify as Orthodox Christians, 10.2% as Greek Catholics, 3.7% as Protestants, 1.9% as Roman Catholics, and 8.7% as “just Christians.” In total, there are approximately 37.9 million Christians in Ukraine.

The remaining population is composed of Jews, Muslims, members of other religious groups, and individuals who do not follow any religion. Although their percentage is much lower than that of Christians, they still number around 5.6 million people.

To gain a better understanding of the topic, it is also important to understand the history of Christianity in Ukraine and why Ukrainians are trying to restrict the influence of the Moscow Patriarchate. Together with Oleh Turii, director of the Institute of Church History at Ukrainian Catholic University, and researcher Anatolii Babynskyi, we discuss the history of church institutions in Ukraine and confrontation between them.

How did Christianity appear on the territory of Ukraine?

Petro Andrusiv, "Baptism of Rus-Ukraine".

The baptism of Kyivan Rus.

Christianity first spread on the territory of modern Ukraine through Greek colonies in Crimea and the Northern Black Sea region, as well as through trade contacts with Byzantium and other Christian countries.

The missionary activity of the Slavic Christian preachers and educators, the brothers Cyril and Methodius, and their disciples in the second half of the 9th century had a connection to the Ukrainian lands. Cyril and Methodius created the first Slavic alphabet as well as the first Slavic translations of liturgical books.

Cyril and Methodius.

Christianity was actively spreading in Kyivan Rus even before the official baptism of the region, specifically during the reigns of Kyivan Princes Askold, Oleh, and Ihor. In 957, the eminent Princess Olha was baptised in Constantinople. Following her baptism, she invited a bishop from Germany to Kyiv.

In 988, Prince Volodymyr of Kyiv embraced Christianity, leading to its establishment as the state religion of Kyivan Rus. Concurrently, the Patriarchate of Constantinople founded the Metropolis of Kyiv.

The Metropolis of Kyiv (Greek: μητρo — mother, πολίτης — city), founded during the Rus-Ukraine Baptism, became the foundational church for all dioceses that emerged in modern Belarus and Russia.

This undermines Russia’s narrative that Moscow is the mother church for Ukrainians and Belarusians because the first metropolis in the region was established in Kyiv.

Metropolis and diocese

In the Eastern Orthodoxy, Metropolis is an area under the canonical authority of a Metropolitan that usually consists of several dioceses. Also called “Metropolinate”. Diocese is a church administrative unit in Eastern Christianity, particularly in the Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches.How did the Metropolis of Moscow appear?

The secular and ecclesiastical elites of Kyivan Rus were receptive to relations with the Latin West. This is evidenced by the exchange of embassies with the Roman Apostolic See and the dynastic marriages of Kyivan princes and princesses with rulers of other European countries.

Hermogenes (Patriarch of Moscow)

The first attempts to divide the metropolis and separate the northern (modern Russia) dioceses from the Kyivan centre took place during the reign of Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky of Suzdal, whose army captured, destroyed, and looted Kyiv in 1169. Among the stolen shrines was the icon of the Virgin of Vyshhorod (believed to be miraculous), which ended up in modern Vladimir.

The definitive division into the Kyiv and Moscow metropolises followed the Council of Florence in 1438-1439. Kyiv Metropolitan Isydore advocated for unity with the Roman Church at this council.

How did the Metropolis of Moscow assert itself?

The decisions of the Council of Florence, which aimed to unite the Eastern and Western Churches, were rejected in Moscow. In 1448, Moscow elected its own Metropolitan, Jonah of Ryazan, without the approval of the Eastern Orthodoxy’s centre in Constantinople. This act gave rise to the wrongful notion of Moscow as the “Third Rome” and its “special mission”, emerging in contrast to church unity and the authority of the Mother Church.

“The Third Rome”

This is how they refer to the various Christian centres that flourished throughout history. Rome is the first, and Constantinople is the second. Moscow has created an ideology in which it sees itself as the successor to these centres.From 1448 to 1589, this Metropolis of Moscow existed in isolation from the rest of the Christian world. Because of its canonical isolation, there were some differences in liturgical practice with other Eastern Churches.

The autocephaly (independence from another country’s Patriarch) of the Moscow metropolis was recognised in 1589, when the tsarist authorities, taking advantage of the arrival of the Patriarch of Constantinople for donations, forced him to proclaim a new patriarchate in Moscow. However, the Kyivan metropolis remained under the rule of Constantinople, not Moscow.

How was the Ukrainian Orthodox Church russified?

Bohdan Khmelnytsky's arrival in Kyiv in 1649

The events of the National Liberation War (1648-1657), led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, marked a turning point in the development of the Metropolis of Kyiv. He hoped to find an ally in the Moscow state, but this alliance turned disastrous for the Ukrainian state’s political, cultural, and religious life.

Following the Treaty of Pereyaslav in 1654 (an alliance between the state of the time on the territory of modern Ukraine and Muscovy), Ukrainian lands gradually lost their autonomy and eventually fell completely under the control of the Principality of Moscow.

Despite the opposition of the clergy of the Metropolitanate of Kyiv, Moscow was successful in re-subordinating the Kyivan throne to its patriarch in 1686.

This matter was “settled” in Constantinople through generous bribes, as the patriarchs there were in a difficult situation under Ottoman rule. Only in 2018, Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople reversed his longtime predecessor, Dionysius IV’s, infamous decision.

The National Liberation War of 1648-1657 led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky

It was aimed primarily at liberating the Ukrainian people from the domination of the mediaeval state of The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (a confederation of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) Bohdan Khmelnytsky was a Ruthenian nobleman and military commander of Ukrainian Kozaks.Why did the Metropolis of Moscow need Kyiv?

At the time of its occupation by the Moscow Patriarchate, the Metropolis of Kyiv was at a more advanced stage of development in both social and church life. This was primarily due to the influence of Western European education and religious culture. Consequently, it rapidly became a source of educated clergy and personnel for Moscow.

Without the contributions of Ukrainian and Belarusian theologians, the educational and liturgical reforms undertaken by the Moscow Patriarchate in the second half of the 17th century would likely have been unfeasible. However, over time, the Kyivan Metropolis was relegated to the status of a mere branch within the Moscow Patriarchate. Hence, its unique characteristics and internal autonomy were gradually eroded and eventually lost.

How did the Russian Empire make the church an instrument of political influence?

Tsar Peter the Great of Moscow

During the reign of Peter the Great, the Moscow Patriarchate was abolished and replaced by the “Holy Synod”. This body governed the Russian Church and effectively functioned as one of the state departments. Concurrently, the tsardom of Moscovia was rebranded as the Russian Empire, a move intended to legitimise claims to the entire heritage of ancient Rus.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the Russian state and church authorities intensified the Russification of the Church in Ukraine. By the mid-twentieth century, this resulted in all Kyivan metropolitans being ethnic Russians.

Russia's claims to the heritage of Kyivan Rus

One of the most widespread historical myths that Russia has used at various stages of history to create an artificial connection with Europe and justify its imperial ambitions. In fact, the centre of Rus was Kyiv, and the territory of modern Russia was known as Zalissia at the time.When and why did the Ukrainian Autocephalous (independent) Orthodox Church appear?

The ruins of St. Michael's Cathedral in Kyiv, which was blown up by the Soviets in 1937.

Following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the new communist government did not recognise religion and launched a massive attack on it. Churches were destroyed, and priests were murdered.

However, it was during this period that the Ukrainian priesthood began to advocate for the Ukrainianization of religious life and separation from the Moscow Patriarchate.

Several meetings and councils were held between 1917 and 1921, resulting in the proclamation of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (here and after — UAOC) in 1921, which did not have a canonically recognised hierarchy.

The All-Ukrainian Assembly of the First Orthodox Council in Kyiv, 1921.

The Moscow Patriarchate reacted extremely negatively to the independent aspirations and actions of Ukrainian priests and laity. In 1930, the Soviet communist regime liquidated the UAOC. The leaders of the autocephalous movement were repressed and killed.

For a short time, during the German occupation, the idea of the UAOC was revived again (1941-1944), when a number of Ukrainian bishops were ordained with the assistance of the Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Poland.

However, as Soviet troops advanced, the “second generation” bishops of the UAOC emigrated to the West, and this Church only existed in the diaspora.

During World War II, the anti-religious repressive policy was somewhat weakened, but this was a strategic goal. Stalin hoped that by doing so, he could boost the USSR’s global reputation and gain the support of the Soviet people. As a result, the Moscow Patriarchate restored its structures in 1943, and the word “Rossiyskaya” (“российская” in Russian) in the Church’s name was replaced by “Russian”(“русская” in Russian) to emphasise its claim to the heritage of all ancient Rus.

Despite some softening in the Soviet government’s attitude toward the Russian Orthodox Church, the secret services closely monitored its internal life and international activities. Many members of its senior clergy were recruited by the KGB as agents.

KGB (State Security Committee)

A Soviet government agency responsible for intelligence, counterintelligence, and suppressing nationalism, dissent, and anti-Soviet activities. The KGB was replaced by the FSB (Federal Security Service) in the Russian Federation.

Following the annexation of western Ukrainian lands by the USSR, the Soviet secret services held the Lviv Pseudo-Council in 1946, where they announced Greek Catholics’ accession to the Moscow Patriarchate. A similar forced “reunification of the Uniates” with the Russian Orthodox Church happened in Zakarpattia in 1949.

Ukrainian Greek Catholics in the USSR were forced to go underground from that time until 1989. They were only legal in the diaspora.

What is the difference between the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Moscow and the Kyiv Patriarchates?

With the beginning of perestroika (1985-1991) in the USSR, the desire for Ukrainian Christians to leave the “patronage” of the Moscow church centre was revived in Ukraine.

In 1989, acknowledging social shifts, the Moscow Patriarchate allowed more self-governance for the Ukrainian Church District within the Russian Orthodox Church. They also permitted this district to be called the “Ukrainian Orthodox Church”. However, this autonomy was mostly for show, as Moscow still aimed to control Ukrainian Orthodox dioceses.

This church district, now known as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate, often downplays its ties with Moscow to its followers. Despite seeming independent, it’s officially just a part of the Russian Orthodox Church, not recognised globally as a distinct church entity. Its bishops are seen as part of the Russian Church.

At the same time, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church emerged from hiding at the end of the Soviet Union’s existence in 1989, significantly weakening the Russian Orthodox Church’s influence on Ukrainian society. At this time, some pro-Ukrainian priests in the West of Ukraine left the Moscow Patriarchate. They reinstated the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and reconnected with its diaspora.

These moves led the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate to seek independence in 1992, but Moscow refused. Its head, Metropolitan Filaret (Denysenko), was then forced to step down. He and some bishops joined part of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church, forming the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate in 1992.

Perestroika

The period of reforms by Mikhail Gorbachev that were supposed to overcome the crises of the totalitarian rule of his predecessors.

Metropolitan Filaret

The Moscow Patriarchate excommunicated Metropolitan Filaret in 1997, calling him a splitter who “dared” to call himself Patriarch of Kyiv and All Rus-Ukraine. Only 21 years later, on 11 October 2018, the Patriarch of Constantinople responded to Filaret’s appeal and withdrew the anathema, restoring his canonical rank.

Since Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, Metropolitan Onufriy, the head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate, has been controversial, particularly in the context of war. For instance, he didn’t honour Ukrainian independence defenders in 2015 and blessed Russian prisoners of war, offering them best wishes, prayer books and chocolates despite their involvement in the war crimes against Ukrainians.

The path to the independence of the Ukrainian church

St. Mykhailo's Cathedral in Kyiv

In the early 2000s, the Ukrainian government and two Orthodox churches in Ukraine, the Autocephalous and the Kyiv Patriarchate, sought to unify and gain independence for the Ukrainian church, recognised by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Both church leaders and government officials appealed for this change.

After extensive negotiations, in 2018, the Patriarch of Constantinople annulled the 1686 charter that had revoked the Ukrainian church’s independence, reclaiming jurisdiction over Ukrainian territory. This shifted the Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s allegiance from Moscow to Constantinople.

In the same year, a Unification Council comprising Ukrainian Orthodox Church leaders was convened to form the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU). While all bishops from the Ukrainian churches were invited, only two hierarchs from the Moscow Patriarchate attended.

Early in 2019, the OCU received the Tomos of Autocephaly from Constantinople. This recognition was later extended by the Churches of Greece and Cyprus and the Patriarchate of Alexandria.

Tomos

Granting a tomos most often means granting the new local church autocephaly, i.e. independence from other Orthodox churches, but in canonical unity with them.

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I signs the Tomos of autocephaly of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine

Russia’s reaction to the autocephaly of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine

It is notable that, even as the issue of Ukrainian autocephaly was being discussed, Russian authorities called a meeting with representatives of the Russian Security Council. This concern illustrates Russia’s attitude toward the Church as a tool of political influence. The Kremlin is attempting to promote its “Russian world” through every available channel.

The Russian Orthodox Church continues its “soft influence” on Ukraine through its Ukrainian branch of Moscow Patriarchate. They use the clergy’s high level of trust among believers as the best representatives of society for this purpose.

Why are the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Orthodox Church dangerous?

The Russian Orthodox Church has been training “church agents” for years to spread imperialist narratives about Russia and the need to return to it, particularly in Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova.

The consequences of this plan are especially visible in the Moscow church branch in Ukraine, where many clergy are anti-Ukrainian. Scandalous discoveries about such “clergy” appear in the media on a regular basis.

The Moscow Patriarchate’s “achievements” include weapon manufacturing and trafficking, depravity of minors, assistance and resource support for Russia’s war in Ukraine since 2014.

The Russian Orthodox Church’s highest ranks are generally linked to the Kremlin and Putin himself. For example, in the democratic world, Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and his cronies face severe sanctions for their support for the invasion of Ukraine and their involvement in the abduction of Ukrainian children.

A Russian priest visits deported Ukrainian children.

The well-known Archpriest Andrei Tkachev, for example, instead of teaching Christian principles and preaching the Gospel message of love, delivers sermons that resonate with the tone of a Soviet-era military and patriotic political commissar. He is an alumnus of the Moscow Military School and graduated from the Department of Special Propaganda at the Military Institute.

Archpriest Andrei Tkachev, one of the main ideologues of the "Russian world" through the "Orthodox" prism (Sanctioned by the European Union and Ukraine)

Archpriest Andrei justifies Russian troops’ actions in Ukraine in one of the videos, calling them an “apocalyptic war” and “purification.” In another, while reading a prayer, he explicitly calls for the use of Grad rockets to bomb Ukrainians.

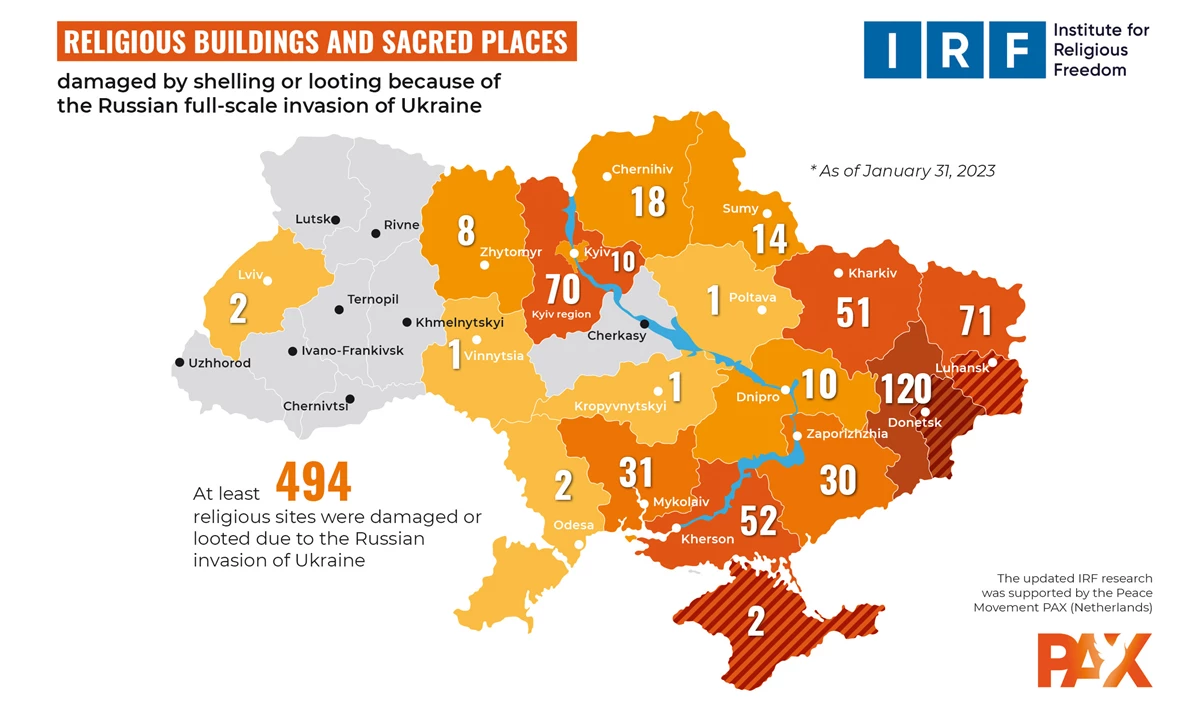

It is ironic that, amid a full-fledged war, the Russian military is destroying churches and religious institutions throughout Ukraine, including those affiliated with Moscow.

Recognising the potential threats and consequences of the Moscow Patriarchate’s activities, the Verkhovna Rada registered a bill to ban the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine on March 29, 2022. The purpose of this bill is to protect Ukraine’s territorial integrity, as Russian cultural occupation is the first step before launching a military invasion. Ukrainians understand this, as evidenced by research by Ukrainian disinformation experts Detector Media:

— All of these propaganda techniques are intended to create the illusion of a religious civil war in Ukraine in order to divide both other states and Ukrainians along religious lines. In reality, all of this is a well-executed performance in Moscow. Recent public opinion polls demonstrate that Ukrainians understand this: 78% of citizens believe that the state should intervene to some extent in the activities of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. 54% of them believe that this religious institution should be officially banned in Ukraine.

More and more former Moscow Patriarchate churches are voluntarily transferring to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, which has simplified the process. 277 churches have made this transition since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. It is necessary to eliminate the Russian Orthodox Church’s influence in other countries as well, because it is not only about Ukraine’s security, but also about the security of Western countries where the Kremlin spreads propaganda and agents through clergy representatives.