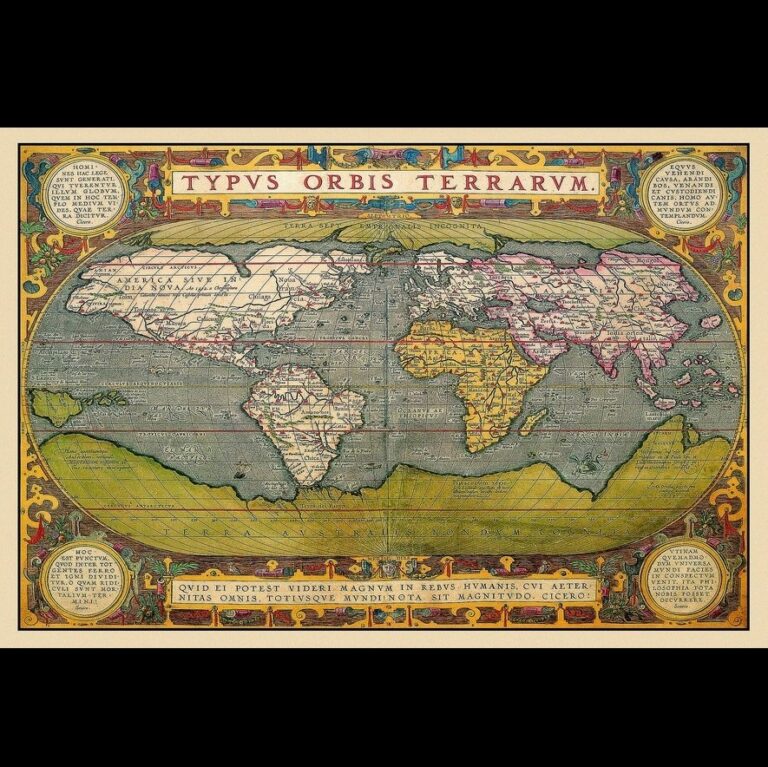

Ukrainian travelers in the late eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries were driven by a desire to explore the world, and they played an important role in the nation’s cultural, scientific, and social life. The world travelers visited remote corners of the globe, discovered new territories, and gained a better understanding of various peoples, cultures, and natural resources.

Unfortunately, Ukrainian travelers were subordinated to the Russian Empire and, later, the Soviet Union during this period, so they frequently traveled and made discoveries on their behalf. This was actively used by Russian propaganda, which for centuries appropriated the achievements of enslaved peoples’ representatives. Despite this, they saw the world through a different lens and held progressive, humanistic views. Even back then, Ukrainians criticized Russian enslavement and imperialism. Today, we can pay tribute to and appreciate the legacy of outstanding Ukrainian explorers and travelers.

Yurii Lysianskyi

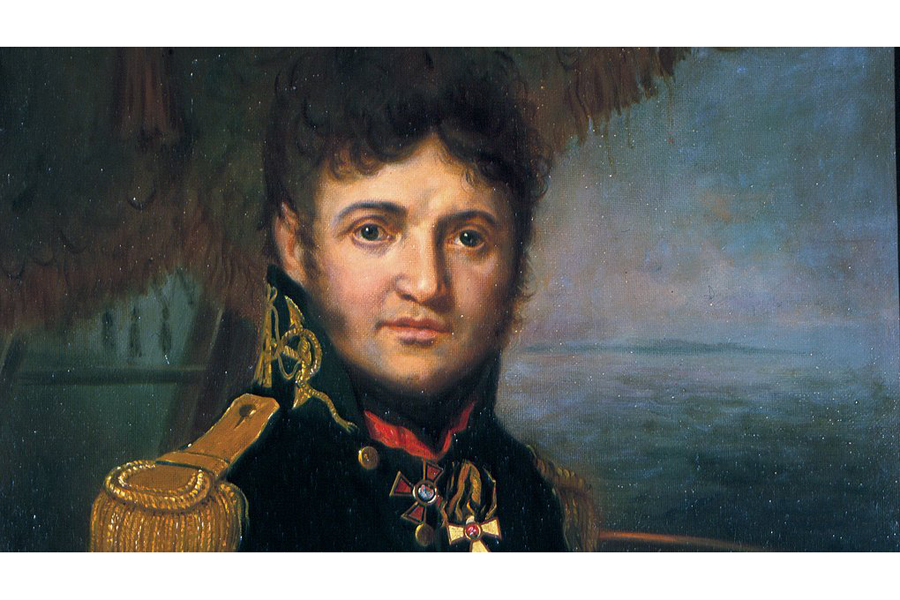

Born to a priest in Nizhyn, Sivershchyna, in 1773. He was a Kozak officer’s descendant, a navigator, a geographer, and the founder of Russian scientific oceanography.

He joined the Navy Cadet Corps at the age of ten, but was forced to graduate early due to the outbreak of the Russian-Swedish War in 1788-1790. The fifteen-year-old was dispatched to the Baltic front right away.

Yurii Lysianskyi. Photo from open sources.

After the war, Lysiansky completed an internship in the United Kingdom before joining the British Navy for another six years. He then participated in several long-distance voyages, including trips to the coasts of North America and the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa. He lived in the United States from 1795 to 1796, where he was introduced to the first President George Washington.

The traveler visited southern Africa in 1797 and became interested in the local people’s living conditions. He was outraged that colonists hunted indigenous people, the Bushmen and Gottentots, for fun. There, he conducted natural history research and acquired a collection of tropical shells and stuffed animals native to the region.

Lysiansky sailed to India in early 1799, where he met high-ranking British military officials, including the Governor General of India. The Ukrainian also visited the provincial governor’s palace, where he spoke about Ukraine and his native Nizhyn. In his diary, he recorded information about Indian life, daily routines, and culture.

Following that, Yurii Lysiansky wanted to head to Australia, but the Russian ambassador informed him in a letter that relations with the British had deteriorated and that he should come to St. Petersburg. However, Lysiansky spent two more years in the UK. The Ukrainian had apparently lost his Russian language skills during his lengthy stay abroad. His brother was even sent to him in order to restore his “gift of speech.”

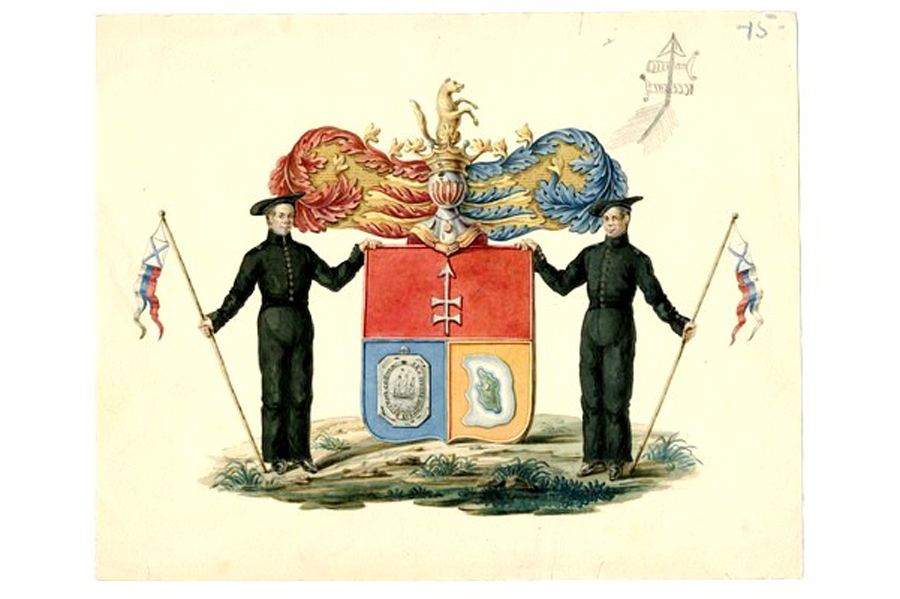

The coat of arms of the Lysiansky family. Photo from open sources.

In 1803, Yurii Lysiansky set sail around the world on the ship Neva. Interestingly, the Russian military command and officials were against it, citing a lack of resources, but a non-governmental Russian-American trading company financed the trip. During the expedition, he conducted scientific research and refined the maps of the time, including the location of Easter Island, using astronomical observations. In addition, he managed to compile a dictionary of the language of the island’s local population and clarify its number.

Lysiansky later arrived in Alaska, then controlled by a Russian-American company. There, he and his crew helped build a new fort, now the city of Sitka, in the United States. The traveler also drew accurate maps of Alaska’s Pacific coast. He wrote about the locals’ poverty and the Russian colonial administration’s cruel policy toward indigenous peoples, including inflated prices and exploitation of the able-bodied population. Russians kidnapped children to force men to work. He witnessed the locals’ starvation and extinction. He delivered dried fish from the ship’s stocks in kayaks to help them somehow.

Later, Lysiansky set sail for the Mariana Islands. On his expedition, he discovered a previously unknown landmass near the Hawaiian Islands, which was later named Lysiansky Island, as well as a coral reef. In his notes, the Ukrainian traveler described the life and customs of the Hawaiian people and compiled a dictionary of the Hawaiian language.

The three-year voyage around the world came to an end in 1806. Yurii Lysiansky was the first in the Russian Empire’s fleet to sail around the globe. He also made geographical, oceanographic, and ethnographic discoveries. Today, Russian propaganda portrays the Ukrainian traveler as the Russian navy’s pride, the first “maloros” [a derogatory term used to describe a Ukrainian native with no national identity — ed.] to sail around the world while denying his Ukrainian origin. Simultaneously, an old manor house where Lysiansky had lived for decades burned down near St. Petersburg in 2018. According to the investigation, it was a deliberate arson.

Fire in the Hannibal-Lysiansky manor. Photo from open sources.

Today, a peninsula on the shores of the Okhotsk Sea, a strait, a river, and a mountain on the island of Sakhalin are named after Yurii Lysiansky. There is a monument to the traveler in his hometown, as well as a memorial room called Traveler of the Kozak Family in Nizhyn University’s Museum of Rare Books.

Ivan Zavadovskyi

Born in 1780 near Hadiach in the Poltava region. He was a world and polar traveler, cartographer, hydrographer, and collector of natural history collections.

In 1819-1821, he served as a deputy captain on the warship Vostok [Russian for East — ed.], which circumnavigated the Southern Ocean in search of a way to the South Pole. This expedition was one of the first to discover Antarctica and the islands near it: South Sandwich, Alexander I, and Peter I Islands. Since the days of Soviet historiography, Ivan Zavadovskyi has been referred to as a Russian, just like Lysiansky.

Ivan Zavadovskyi. Photo from open sources.

One volcanic island has been named after Zavadovskyi. South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands issued four Zavadovskyi Island postage stamps in 2016. Another island on the West Ice Shelf near Antarctica bears his name as well. Ivan Zavadovskyi is one of the main characters in the film story Antarctica by prominent 20th-century Ukrainian director Oleksandr Dovzhenko.

In 1837, the sailor was buried in Odesa. Unfortunately, the Bolsheviks destroyed his grave. However, on Prymorsky Boulevard in Odesa, there is a house of Rear Admiral Ivan Zavadovskyi that was built in the last years of his life. It started as an income house, then became a hotel and restaurant.

Ivan Zavadovskyi's house in Odesa. Photo from open sources.

Yehor Kovalevsky

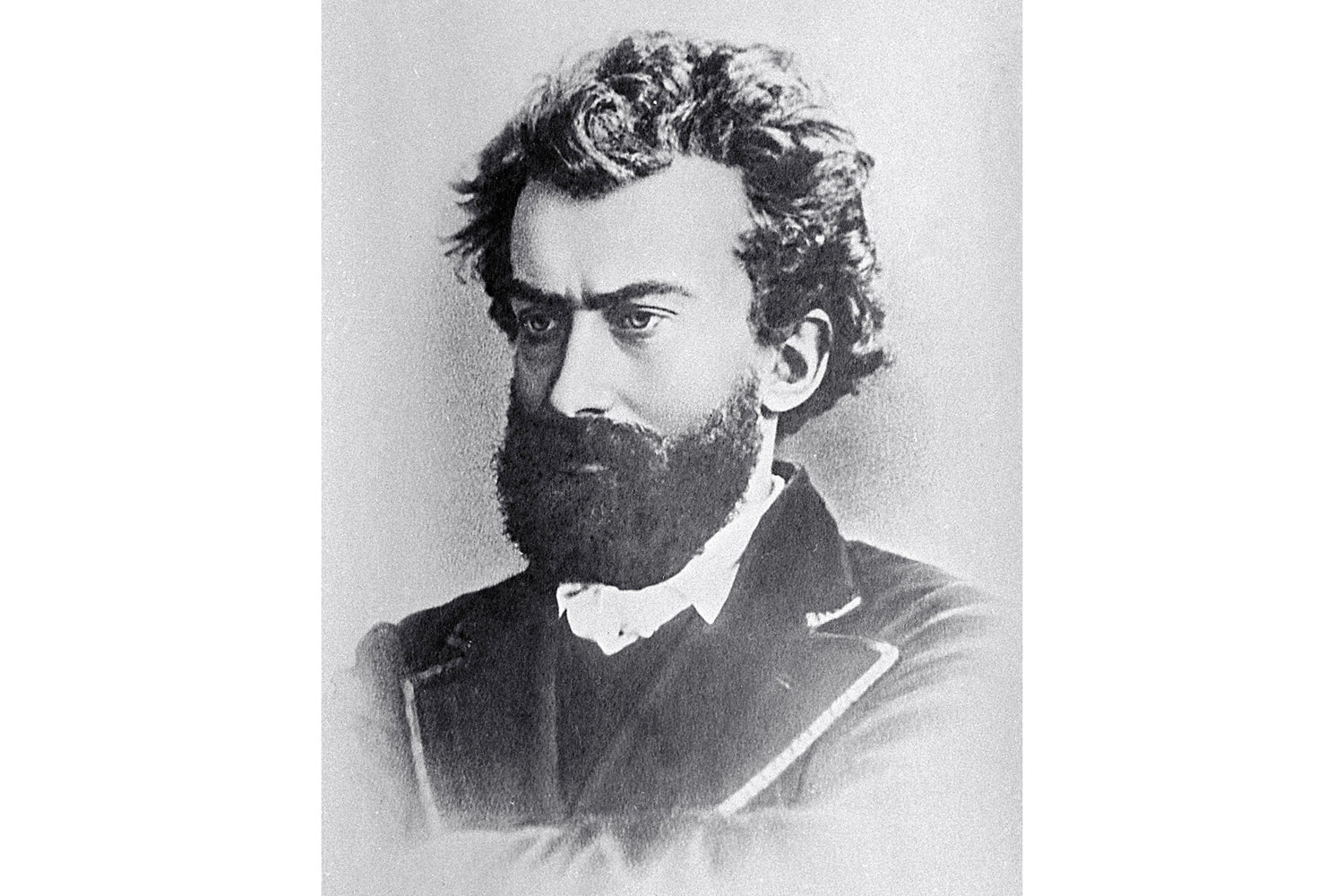

Born in 1809 in the village of Yaroshivka near Kharkiv in the Slobozhanshchyna region to a large family of landowners. He was a traveler, writer, geologist, and archaeologist, one of the first geographers and orientalists of the Russian Empire.

Yehor Kovalevsky. Photo from open sources.

Kovalevsky graduated from Kharkiv University’s Faculty of Philology, founded by his great-uncle Vasyl Karazin. He and his older brother traveled to the Russian Altai in 1830. He spent seven years in gold prospecting expeditions there before being sent to Montenegro to search for gold deposits in 1837. However, he only discovered iron ore, lead, copper, and marble-like limestone deposits. During the excavations, the scientists also uncovered the ruins of Dioclea, a Roman city in Greece. Kovalevsky described the relief and geological structure of Montenegro.

In the early 1840s, Kovalevsky visited Khiva and Bukhara in Uzbekistan, one of the main areas of Russian expansion at the time. Additionally, he traveled to North India, Kashmir, and Afghanistan. At the same time, the scientist explored the Carpathians, as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania, and Bulgaria.

In January 1848, he led an expedition to Egypt in search of gold, precious stones, and the exact location of the Nile River’s origin. They set out from Cairo, intending to reach Khartoum, Sudan’s capital. The geologist correctly identified gold deposits and established a mining factory.

In 1849, he published The Journey to Inner Africa, in which he compared enslaved Africans to Russian serfs and criticized human enslavement. This angered the emperor, so Kovalevsky received a severe reprimand and eight days in a military prison. However, he could not take advantage of these “charms” of the Russian Empire because he was already on a new mission to China, where he was sent to settle trade disputes and accompany a spiritual mission to Beijing. After this trip, in 1851, the Kuljiin Treaty was concluded, which contributed to developing the Russian Empire’s trade with Western China. At the same time, Kovalevsky studied the flora and fauna of Mongolia.

From 1856 to 1861, he headed the Asian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. At the same time, he became one of the founders and deputy chairman of the Russian Geographical Society. In 1856, he was elected a corresponding member, and in 1857, an honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. In addition, Yehor Kovalevsky founded the Literary Foundation and personally managed it. This organization helped writers who found themselves in a difficult situation. As a young man, he was in close contact with the prominent Ukrainian writer Mykola Hohol and supported the legendary Ukrainian poet and artist Taras Shevchenko.

Mykola Myklukho-Maklai

Born in 1846 in the village of Yazykovo, Novgorod province, into a family of Ukrainians. His father was a nobleman in the Sivershchyna region, descended from a family of Zaporizhzhia Kozaks, and his mother was from a Polish-German Russified family. Myklukho-Maklai was a world-famous traveler, polyglot, geographer, ethnographer, and anthropologist. He wrote approximately 160 scientific works during his lifetime.

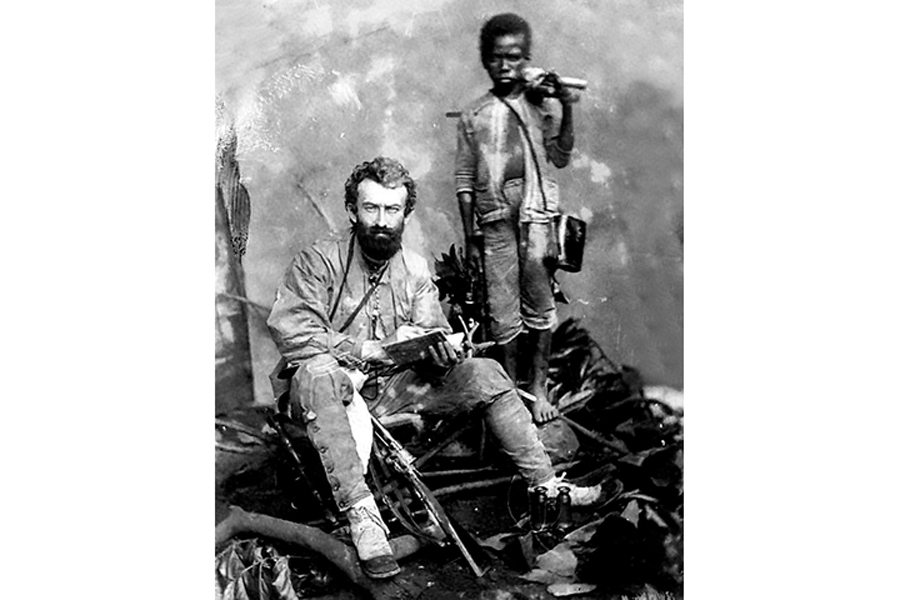

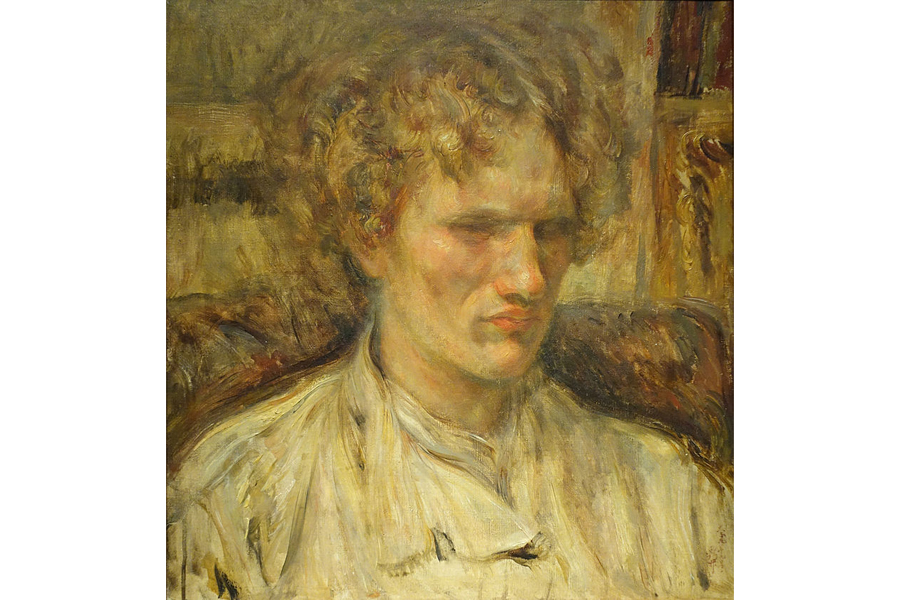

Mykola Myklukho-Maklai. Photo from open sources.

The scientist researched the anthropology and ethnography of indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia, Australia, and Oceania (the islands of Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia). During 1871-1872, he lived among the Papuans of New Guinea’s northeastern coast (then known as the Maklai Coast). A river was also named after him. The Ukrainian fought to protect the rights of the Papuans, against the preparation of New Guinea’s colonial partition, against the German Empire’s annexation of the Maklai Coast, and racism and colonialism. Instead, the Russian press reported that he desired Great Britain to occupy New Guinea. Among the Savages of New Guinea, his travel journal was published in Ukrainian in Kyiv in 1961.

Myklukho-Maklai on the Malacca Peninsula, 1874-1875. Photo from open sources.

In 1876, Myklukho-Maklai traveled to western Micronesia and northern Melanesia, where he conducted ethnographic and anthropological research and collected information about slave traders. Later, he traveled to Singapore, and then moved to Sydney, Australia, on the recommendation of doctors due to illness. There he became an honorary member of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, conducted comparative anatomical, anthropological, and ethnographic research, and published articles. A marine biological station was established in Sydney at his initiative.

Marine biological station. Photo from open sources.

Myklukho-Maklai began writing Notes on Kidnapping and Slavery in the Western Pacific and The Maklai Coast Development Project at the end of 1881. On April 8, he published an open letter to the commodore supporting Oceania’s indigenous people.

Commodore

A military rank in the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Netherlands. A ship's commander who does not hold the rank of admiral.After returning to Europe, Mykola Myklukho-Maklai lectured in London, Berlin, and Paris. He also studied his homeland, in particular the life and customs of local communities of Polishchuks, Drevlyans, and the fauna of the Crimea and the Black Sea. In addition, he twice visited Malyn in Polissia to see his mother and brother’s estate. Interestingly, in 1980 and 1988, the scientist’s grandson Robert came to Malyn from Australia.

The memory of the researcher is honored not only in Ukraine, but also in many other countries around the world. For example, a bust of him has been placed in Jakarta, Sydney, and Kuala Lumpur. Apart from that, his memorial was erected at Cape Garagasi (Papua New Guinea) on the site of his hut.

Oleksandr Bulatovych

Born in 1870 in Orel (now the city in a part of Russia), Slobozhanshchyna, into a noble family. He is known mainly as an African explorer, ethnographer, and geographer.

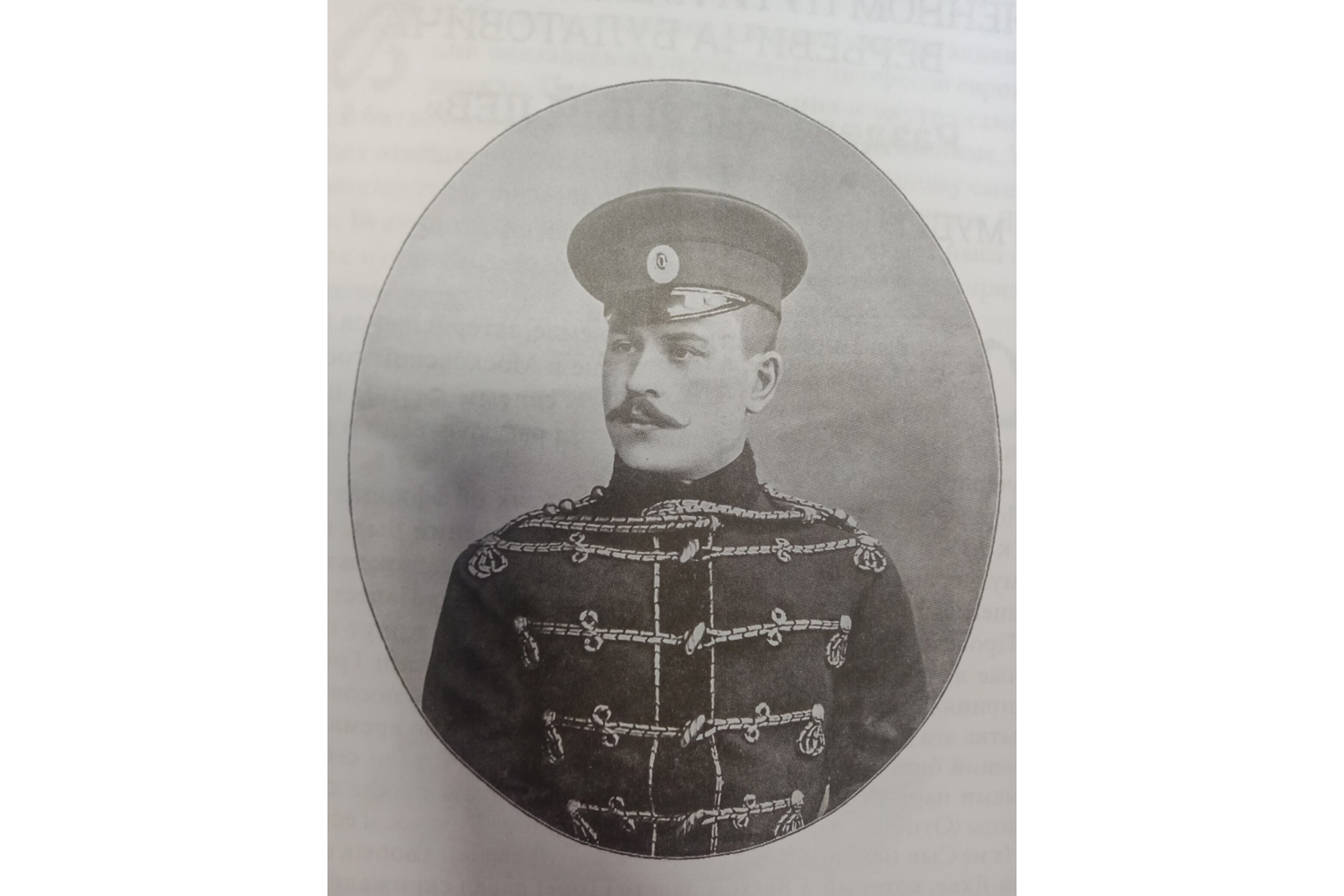

Oleksandr Bulatovych, 1892. Photo from open sources.

In 1896, he ran 350 versts (approximately 373 kilometers) across the mountainous desert on camels from Djibouti to Harar in East Africa in three days and eighteen hours, which was at least six hours faster than professionals could do at the time.

During 1897-1899, Bulatovych made three expeditions to Ethiopia, which had not yet been explored at that time. During one of them, as a member of the Red Cross, he was in charge of a hospital for Ethiopian soldiers fighting against the Italian colonizers. Bulatovic visited the capital, Addis Ababa, and the central and western provinces of the country. Stories from this trip were included in his diary book From Entoto to the Baro River, which was published in 1897.

In 1898, he reached the southern shore of Lake Rudolph and crossed the Kaffa mountain region, which was not yet known to Europeans. Bulatovic recorded these lands on maps, studied their geology and hydrogeology, and gathered a collection of mineralogical and ethnographic materials. In addition, he refuted the hypothesis that the Ethiopian Omo River was a tributary of the Nile, and instead marked the real tributary, the Sobat, on the map. In 1899, he explored the western part of Ethiopia, bordering Sudan.

Later, Oleksandr Bulatovych became a monk and went to Mount Athos, where he took up schisma or alienation from the world. In 1910, he became a hieromonk, and for the next two years, he organized an Orthodox monastery in Ethiopia. Disappointed with the official Russian Orthodox Church, the traveler opposed the Synod and the Russian state church ideology: he wrote articles and pamphlets. In 1913, he was detained and exiled to his family estate in Ukraine, the village of Lutsykivka in the Slobozhanshchyna region. Bulatovych participated in the First World War as a regimental priest. He was taken prisoner but managed to escape and return to Lutsykivka.

Pamphlet

A type of literary or journalistic work, usually directed against the political system as a whole or a separate part of it, against a particular social group, party, government, etc.

Hieromonk Antonii (Bulatovych). Photo from open sources.

Anton Omelchenkо

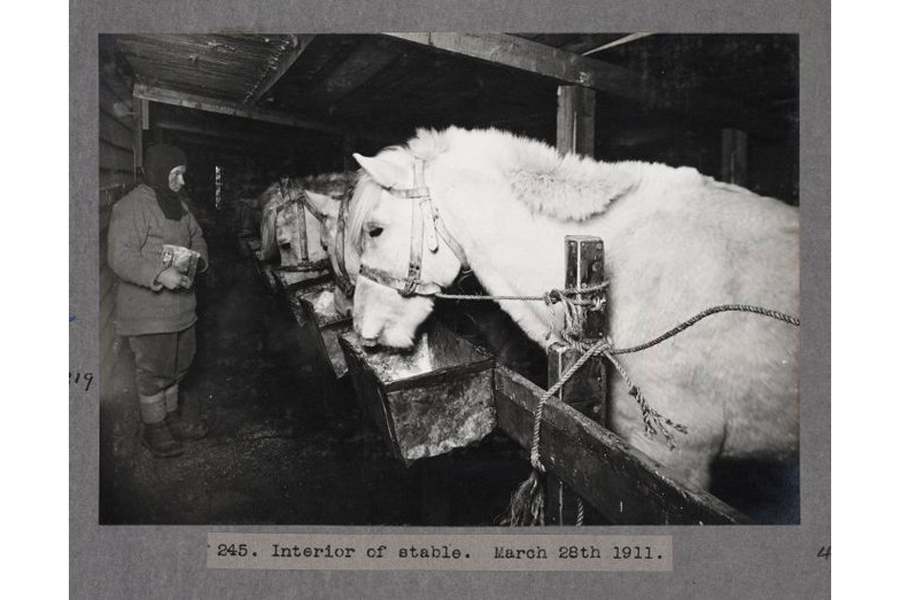

Born in 1883 in the village of Batky, Poltava region. He was a member of Robert Scott’s expedition, which was also one of the first to reach Antarctica. The traveler crossed the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans on the Terra Nova ship. As part of the expedition, he mainly took care of horses, as his poor childhood forced him to learn this skill at an early age. A photographer on board took a series of photos and recorded a video of Omelchenko dancing the national Ukrainian dance hopak.

Anton Omelchenko in a stable, March 28, 1911. Photo from open sources.

Following this expedition, Omelchenko received membership in the British Royal Geographical Society. The travelers were honored with a banquet and awards at the royal palace. Anton Omelchenko was one of the first Ukrainians to be honored and given a lifetime pension by King George V. However, when diplomatic relations between the USSR and the United Kingdom were cut off in 1927, pensions were halted.

Omelchenko flew home and participated in the First World War almost immediately after the expedition ended. He returned to his village after the war ended and got a job as a postman. He died in 1932 from a lightning strike near his home.

A bay on Oates Bank, discovered by British explorers in 1958, was named in honor of Anton Omelchenko. Also, in celebration of the Antarctic expedition’s 100th anniversary in 2012, rocks on Ross Island on the northern coast of Victoria Land in East Antarctica were named after him.

His grandson Viktor Omelchenko was a member of the Ukrainian Antarctic expeditions VI, IX, and XI, and his great-grandson Anton was a member of the XX and XXIV. Viktor took a lump of soil from his grandfather’s grave to Antarctica, where he exchanged it for a stone, which was later used to create the memorial bas-relief composition Antarctica.

The XX Antarctic expedition. Photo from open sources.

Vasyl Yeroshenko

Vasyl Yeroshenko was born into a peasant family in the village of Obukhivka in Slobozhanshchyna (now part of the Russian Federation) in 1890. He lost his sight at the age of four due to illness. He is known as a writer, traveler, Orientalist, and linguist. He was proficient in Ukrainian, Russian, English, Esperanto, Turkmen, and Japanese.

Esperanto

The most common artificial language of international communication.

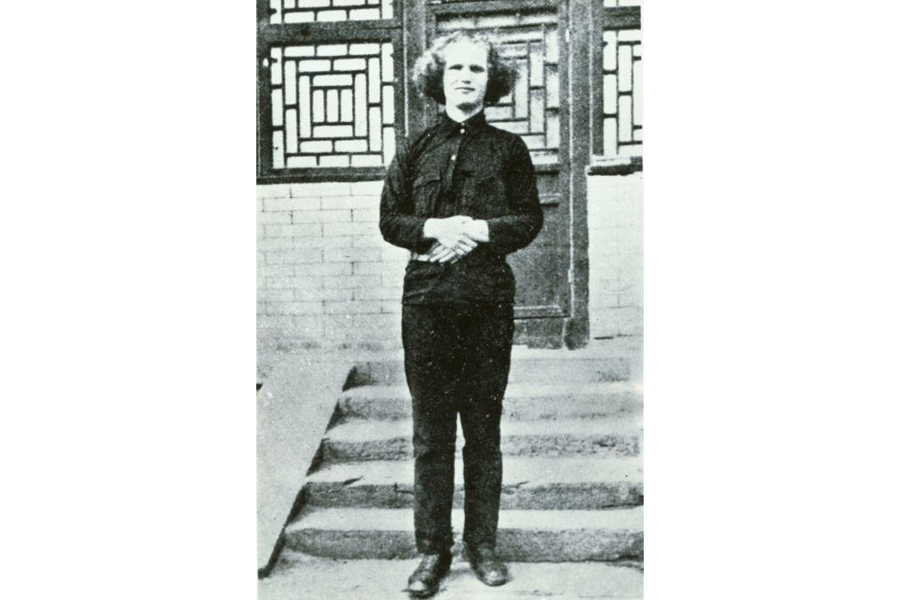

Vasyl Yeroshenko. Photo from open sources.

Vasyl Yeroshenko was published in English in London: a series of his fairy tales was issued and his poetry was published in magazines. He also wrote works in Japanese. His short story The Story of a Paper Flashlight was published in a Tokyo magazine in 1916. In 1953, his fairy tales were included in the multi-volume Library of Japanese Children’s Literature. In 1956, the Japanese researcher Ichiro Takasugi published a book about the Ukrainian author himself, The Blind Poet Erosienko (the surname was changed to match the Japanese pronunciation).

Yroshenko lived in France, England, Siam (now Thailand), Burma (now Myanmar), India, China, Chukotka, and Central Asia. He did, however, spend half of his life in Japan. The famous artist Tsune Nakamura’s portrait of Yeroshenko, which is now housed in the Tokyo Museum of Modern Art, is included in the history of Taisho art. Ge Baoquan, a Chinese literary critic, published a book titled Lu Xin and Erosienko. The Vasyl Yeroshenko Espero Charitable Foundation has been active in Ukraine since 2007, spreading the writer’s creative legacy and promoting the Esperanto movement.

Lu Xin

A Chinese writer, a friend of Yeroshenko's, on whose recommendation he taught Esperanto at Peking University.

Portrait of Vasyl Yeroshenko. Author: Tsune Nakamura.

Sofia Yablonska

Yablonska was born to a priest in Hermaniv (now Tarasivka) in Halychyna in 1907. She was a reporter and journalist who spent 30 years publishing travel stories in Halychyna magazines.

Sofia Yablonska. Photo from open sources.

Sofia studied acting in her homeland before moving to Paris to pursue a career as an actress in 1927. She began her career as a model, then went on to study documentary filmmaking and eventually became a film reporter. At the same period, she became acquainted with Stepan Levynskyi, a Ukrainian writer, explorer, and orientalist. Traveling to exotic locations became trendy among the French artists Yablonska belonged to over time. As a result, she was inspired to travel the world too.

Her first trip was to Morocco in 1928, where she traveled from Casablanca to Marrakech, Mogador, Taroudant, and Agadir. Yablonskaya returned to Paris at the end of March 1929. In her 1932 book Charm of Morocco, she highlighted the traditions, culture, and hospitality of the Berbers, as well as her impressions.

Berbers

An indigenous ethnic group in North Africa that lives on the territory from the Atlantic Ocean to the oasis of Siwa in Egypt, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Niger River.In December 1931, the Ukrainian set off on a globe tour to shoot documentary essays for the Yunan Fu Wholesale Society. Sofia Yablonska traveled to Egypt’s Port Said, Djibouti, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Laos, Cambodia, China’s Yunnan Province, the Malay Archipelago, Java, Bali, Tahiti, Australia and New Zealand, and the United States and Canada. She was a big fan of traditional apparel, especially Ukrainian clothing, so she brought it back from her travels and wore it all the time.

Traditional clothing. Photo from open sources.

In January 1935, she returned to Ukraine after traveling around the globe, where she arranged creative meetings and public performances. At the same time, the traveler began writing reports and essays for local periodicals such as Women’s Fate, Us and the World, Toward, and others.

Yablonska traveled to Indochina in September 1939 and later settled in China. She met and later married Jean Oudin there. The Ukrainian-French couple has three boys. At the same time, this period in Sofia Yablonska’s life was marked by the deaths of loved ones: her father, who committed suicide after learning of the Soviet occupation, her close friend Stepan Levynskyi, her sister Olha, and her mother.

Sofia Yablonska with her husband. Photo from open sources.

The family relocated to Paris in 1946. After her husband died in 1955, she moved to the French island of Noirmoutier. She began studying architecture and design there, and built a Vendée-style villa. This positive experience enabled her to continue doing it professionally. The municipal commission of architects awarded one of her ideas the status of artistic asset of the island.

Vendée

A department in western France, one of the departments of the Pays de la Loire region.

Sofia Yablonska's villa. Photo from open sources.

Yablonska also began working with Ukrainian poet Marta Kalytovska, who inspired her to resume her literary work. She was writing a memoir called Conversation with My Father at the time, in which she described her early years in Ukraine.

The traveler’s life was cut short on February 4, 1971, in a car accident on the way to the publishing house, where she was carrying a new manuscript, Two Measures, Two Weights. Marta Kalytovska published this book in Ukrainian the following year. She also organized, translated, and published several works by Sofia Yablonska in French, including Mon enfance en Ukraine (French for My Childhood in Ukraine).

Yevhen Fedynskyi

Born in 1920 in Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk) in Halychyna. He was a traveler, a polyglot, and the first Ukrainian to travel to northern Brazil and describe the local tribes.

Yevhen Fedynskyi. Photo from open sources.

Yevhen and his brothers grew up in a family where the Ukrainian spirit prevailed. The boys had an active social position, belonged to the Ukrainian scouting organization Plast, and later joined the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). During the Second World War, Yevhen was sent to a penalty battalion for his patriotic activities. However, he managed to escape and get to Vienna, which was also occupied by the Soviet government. There he was recruited to serve in the NKVD as a translator.