On 1 March 2014, at 5:43 p.m., a news report titled “Russia has declared war on Ukraine” appeared on the Ukrainska Pravda website. At this exact time, the Federation Council of Russia publicly announced it would send Russian troops into Crimea, even though its troops were already there.

Despite the fact that there were no active hostilities on the peninsula, the annexation of Crimea marked the start of the 21st-century Russo-Ukrainian war. Over the past 8 years, I have conducted over 200 interviews with Crimeans in hopes of answering the main questions about these events.

How annexation became possible

To understand how the annexation was possible, we need to look decades into the past. Soviet authorities viewed Crimea as a territory where they could shape an almost ideal “Soviet people.” (Of course, Russian people would maintain the highest status, or “leading role,” in the Soviet Union.) Between 1941–1944, Germans, Italians, Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Armenians, and Bulgarians were deported from Crimea. Some of these peoples did not receive the right of repatriation until the late 1980s. Instead, peasants from Russia and Ukraine, along with KGB and Soviet Army officers who were loyal to the authorities, were brought to Crimea to replace them.

A call for Russians to move to the occupied Crimea.

In the 1950s, when Crimea was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR, Ukrainian kindergartens and schools were opened there. But over time, non-Russians were discriminated against, which is normal in Russian politics. For example, in 1982, the Ukrainian Polytechnic Boarding School in Simferopol was reorganised into a boarding school for children with learning disabilities. And in Bakhchysarai, after the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, a former Muslim educational institution – Zıncırlı Medrese – was turned into a psychiatric hospital.

In Crimea, the Soviets pursued a consistent policy of discrediting Ukraine. The “Krymskaya Pravda” weekly newspaper, which had a circulation of 30,000 copies, actively spread hate speech against Ukrainians. At the turn of the century, its editor-in-chief Mykhailo Bakharev wrote that “the Ukrainian language is the language of the mob” and that Ukrainians as a people do not exist. The paper published articles titled “Ukrainists and Little Russians” and “Ukraine is not Russia, Ukraine is a disease.”

Mikhail Bakharev's book "We have returned to you, Motherland"

The publication was also consistently Turcophobic. An article by Natalia Astakhova titled “Brought with the Wind” caused an outcry and a lawsuit against the newspaper. It included the following message (translated from Russian): “Pray tell, is there anything left in this unfortunate, tortured Crimea, that you would not abuse? Land, sea, wine, mountains, gardens, vineyards, cities, villages — everything is covered with a web of your claims, everything is either ruined and plundered, or doused with the impurities of your thoughts. All that’s left is the sky. And even the sky is full of the muezzin’s cry, which blocks all the other sounds of a previously peaceful life.” This article was published in 2008, the same year its author received the title of “Honoured Journalist of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.”

Muezzin

A person who proclaims the call to the daily Muslim prayer.

Russian occupiers in Sevastopol

After Ukraine regained independence in 1991, organisations that were financed by Russia and promoted the “Russian world” still operated in Crimea. These included the “Russian Commune of Crimea”, the “People’s Front of Sevastopol – Crimea – Russia,” and the “Crimean Cossacks.”. As early as 2007, some of these organisations held events with the slogans “The future of Ukraine is in union with great Russia,” “Ukraine without Crimea!,” and “We do not love Ukraine!”

There are also reasons to believe that during the presidency of pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych, many personnel of the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) in Crimea were working for the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (FSB). “We don’t expect a threat from that side,” an SSU officer once said when asked if those who go on business trips to Russia are interrogated in the same way as those who go to the USA. After Russia occupied Crimea, 86.4% of Crimean SSU employees defected to the FSB.

Was Crimea completely pro-Russian?

During the Revolution of Dignity, political technologists on the peninsula actively fueled fear of “fascists” and “Banderites”. In December 2013, the slogan “Fascism will not pass” appeared in videos. Billboards in Crimea portrayed a dark future with Ukraine, supposedly under the rule of Nazis, and a bright future with Russia. Postcards with photos, names, and surnames of participants in the Revolution of Dignity appeared in mailboxes with the words “This person contributed to the flourishing of fascism in Crimea!”

However, a fear of “fascists” did not influence many Crimeans to want to separate from Ukraine. On 4–18 February 2014, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology and the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation conducted a survey. It showed that only 41% of Crimeans supported joining Russia.

A rally in Simferopol on 26 February 2014 also demonstrated that there were more pro-Ukrainian activists than pro-Russian ones, even though the latter were supplemented by visitors from the Kuban region in Russia. According to various estimates, the ratio of pro-Ukrainian to pro-Russian demonstrators was between 3:1 and 5:1.

Photo: Stas Yurchenko

On 27 February 2014, unidentified military personnel occupied the Supreme Council of Crimea and the Council of Ministers and filled the streets of Simferopol. Within a few days, Russian propaganda started telling people that this was something to be happy about. Children gave flowers to the occupiers, and smiling girls took pictures with them.

Petro Koshukov, who was working as a fixer for Al Jazeera at the time, interviewed locals at a pro-Russian rally in Simferopol on 2 March 2014. “Why have you come to the rally?” he asked. They responded “We are against fascism, we are for the right to communicate in Russian.” – “So, do you really want Crimea to become part of Russia?” – “No. We just want there to be no fascism and to have the right to communicate in Russian.” After conducting dozens of short interviews, Koshukov found that none of the respondents wanted Crimea to join Russia.

Photo: Stas Yurchenko

But under the pressure of propaganda, people began to believe that they wanted to live in Russia. A year before the annexation, I spoke with student-interns in the Supreme Council of Crimea. They all said that Crimea is Ukraine. Within a year, some of them left the peninsula, and some were photographed smiling near banners supporting the “Russian Unity” political party.

Pro-Ukrainian rallies also took place during the annexation, but it quickly became dangerous to participate in them. About 200 people who had gathered in Sevastopol for Shevchenko Days were attacked by “guardians of justice”. BBC journalist Ben Brown tweeted about the protesters getting kicked and punched.

Photo: virtual museum of Russian aggression

Why did our military surrender the region without fighting?

At that time, Yurii Holovashenko was the commander of the mountain infantry battalion of the 36th Separate Coastal Defence Brigade stationed in the Crimean village of Perevalne. In Viktor Hrom’s documentary film “Crimea. Surrounded by treason,” Holovashenko says that the Ukrainian military was preparing equipment and snipers were stationed in a park. His deputy Yevhenii Budnik testified that they were ready to station themselves in mountain passes and road junctions in order to stop Russian columns. But they did not receive an order from the brigade commander, Colonel Serhii Storozhenko. After speaking with the Russian military, he announced the decision to lay down arms and surrender the brigade.

Photo: RFE/RL

On 1 March 2014, Denys Berezovskyi was appointed commander of the Ukrainian Navy. The next day, he switched to the side of the occupiers and ordered his subordinates to surrender their weapons.

In the first days of the occupation, Admiral Yurii Ilyin was the Chief of the General Staff of the Ukrainian Navy, but he could not be found. Duties were performed by Vice Admiral Serhii Yelisieiev. “Where is Yelisieiev? – In the hospital. – OK. Where is the Chief of Naval Staff, Rear Admiral Shakura? – In the hospital. – OK. So who commands the fleet? – Not clear.” This dialogue is heard in the film “Crimea. How it was,” recalls 2nd rank Captain Oleksandr Honcharov, deputy commander of the surface ships brigade. It seems that the command in Crimea knew what was happening but stayed silent in order to dodge any responsibility.

Denys Berezovskyi

The behaviour of the then-acting Minister of Defence of Ukraine, Ihor Teniukh, remains unclear. In TV interviews, he said that the sailors had clear orders from the General Staff. Later, the sailors testified that the order was to “not provoke,” to “refrain from active actions,” and that combat readiness was reduced to ordinary. But whoever acted without orders or even against them was able to keep their equipment and, therefore, their base. For example, under the command of Colonel Ihor Bedzai, the 10th naval aviation brigade moved helicopters and airplanes from the airfield in Novofedorivka near Saky to Mykolaiv. Colonel Bedzai died on 7 May 2022 while performing a combat mission during the full-scale war.

Ihor Bedzai

There is still controversy over whether Ukraine could have effectively fought back. On the one hand, in 2003, the Ukrainian authorities stopped the aggressor on Tuzla Island. On the other, in 2014, after President Yanukovych, Ukraine was extremely weakened. The special services had a lot of Russians who worked in Russia’s favour, the Ukrainian army lacked resources due to thefts and looting, and many soldiers did not even know how to shoot.

Another important factor was the Ukrainian army’s mental unpreparedness for a war with Russia. Many were still influenced by the myth of “brotherly nations”. It is telling that Colonel Yulii Mamchur, who led the Ukrainian military in Belbek, sang the Soviet song “Vstavai, strana ogromnaya!” (“Arise, Great Country!”), a common practice in the Russian military.

Photo: Kuba Kaminsky, Euromaidanpress

Many Ukrainian commanders were convinced by their Russian counterparts that the Russian army provided better perks, new equipment, apartments, and quick promotions. Many also realised that if they did not switch to Russia’s side, they would have to leave Crimea.

But not everybody was a traitor. Fixer Petro Koshukov told the story of a man from Sevastopol – let’s call him Vasyl. An ethnic Russian, he joined the Ukrainian Navy in the early 1990s almost by accident. While the Ukrainian Navy was hardly getting by, the sailors of the Russian Black Sea Fleet were receiving high salaries. But during the occupation, after seeing the meanness and unbelievable lies of Russia, Vasyl realised that he stands on the side of truth and will continue to serve Ukraine, now in Ochakiv.

A little less than a third of the military violated their oath to the Ukrainian people. A little more than two-thirds went to the mainland, many of whom later served in the Anti-Terrorist Operation zone and now protect Ukraine from the Russian aggressor.

Were the Crimean Tatars supposed to defend Crimea?

Crimean Tatars make up 12.6% of the population in Crimea. This is less than 240 thousand people, including men, women, and children. On 14 March 2014, there were 22,000 well-trained Russian soldiers in Crimea.

It is important to note that up until 2014, Crimean Tatars were not accepted into the security forces of Ukraine. Horror stories were spread among the Ukrainian military that Crimean Tatars were Islamist terrorists who wanted to give Crimea to Turkey. In general, the security forces acted against the Crimean Tatars. For example, in 2008, the “Berkut” riot police demolished their buildings on Ai-Petri mountain. In 2009, a stun grenade was thrown into a residential house in the village of Myrne.

Photo: Crimean Solidarity

At the same time, the Crimean Tatars were ready to fight against the occupiers. They even held negotiations with the Armed Forces of Ukraine, says Isa Akayev, commander of the “Crimea” unit who fought in the Donbas and is still fighting in the full-scale war. However, the Crimean Tatars quickly realised that the Russians already fully controlled the peninsula.

There is also another answer to reproaches of “Why didn’t the Crimean Tatars come forward?” Some, such as Reshat Ametov, did – and they died a horrible death.

Isa Akayev, photo: Ukrinform

Did a lack of decisive action hold Putin back or untie his hands?

Yes, the UN Security Council organised a first emergency meeting on 28 February 2014. Yes, they promised to remove Russia from the G8 and then did. Yes, the presidents and prime ministers of European states strongly condemned Russia’s actions. Yes, harsh economic sanctions were promised. Yes, Western countries acknowledged Russia’s “referendum” on the status of Crimea was illegitimate.

At the same time, they called for de-escalation and a diplomatic resolution to the issue. This influenced Ukrainian government officials, who were afraid that if they started shooting, they would be accused of escalation. On 7 March, US Defence Minister Chuck Hagel thanked Igor Teniukh for showing “admirable restraint.”

Photo: Reuters

Calls for de-escalation were only followed by the Ukrainian side, and Putin took advantage of this. Neither verbal condemnations nor promised sanctions had any effect on him. At that time, the West still believed it was possible to come to an agreement with Russia.

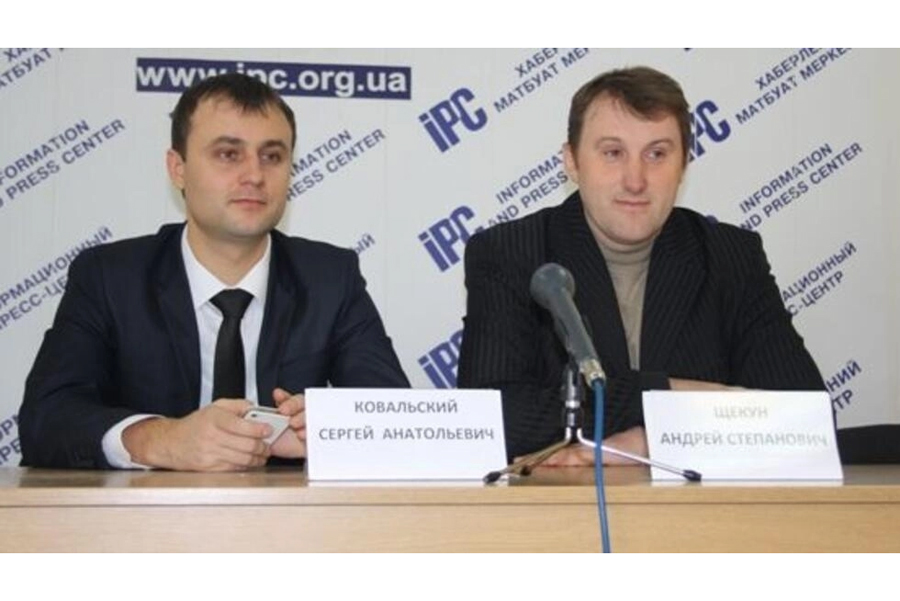

A week before the Russian-organised “referendum”, activists Andrii Shchekun and Anatolii Kovalskyi were kidnapped. Oleksandra Tselishcheva, a local reporter who worked with London-based journalists, was told that “This is not interesting news. If there had been a murder, then there would be something to film.”

Photo: Sergey Dmitriev/rfi.

And then there was a murder – Reshat Ametov was killed. On 3 March 2014, the Crimean Tatar activist went to the Council of Ministers for a solitary silent protest. There are photos of him being forcibly pushed into a car. After 12 days, Ametov’s brutally mutilated body was found 60 kilometres from Simferopol. This was the first death as a result of the occupation, and the world turned a blind eye. Even Ukraine kept it quiet.

All of this untied Putin’s hands. He tried to feel for red lines, but there were none. The Russians went further.

Farewell ceremony with Reshat Ametov

Why we reacted so strongly this time

The puppet government scheduled the “referendum” on the status of Crimea on the first day of the occupation. It was supposed to take place on 25 May. However, the date was moved up twice: first to 30 March and finally to 16 March. Invitations even came for people who had passed away. In general, this event was held using the same methods practised in Russia and in the 2004 elections in Ukraine. “Carousel” vote rigging, misuse of administrative resources, the import of Russians from Kuban, permission to vote with Russian passports, and more fraudulent activities took place.

Pro-Ukrainian residents decided not to go to the “referendum” in order not to legalise it. Despite this, Russia announced that the voter turnout was 83.1% and that 95.5% of people voted in favour of Crimea joining Russia. If you calculate the official figures, apparently 123% of Sevastopol residents voted. According to experts, the actual voter turnout was under 40%, and only about 30% of residents voted for Crimea to join Russia.

Two days later, on 18 March, the “Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Crimea on the admission of the Republic of Crimea to the Russian Federation and the formation of new subjects in the Russian Federation” was signed. Symbolically, on that same day, Reshat Ametov was buried. An ensign of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Serhii Kokurin, was also killed on the same day. He was shot by the Crimean “self-defence force” on a military base in Simferopol.

Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Crimea on the Accession of the Republic of Crimea to the Russian Federation and the Establishment of New Entities within the Russian Federation

A month and a half later, hostilities began in Donbas. And over the next eight years, Crimeans, mainland Ukrainians, and the world learned what it means to live under Russian occupation: kidnappings, imprisonment of the innocent, odious trials, silencing, and the impossibility of doing honest business. Russian occupation also brought the persecution of certain segments of the population: not only activists and citizen journalists, but also members of the Muslim organisation Hizb ut-Tahrir, Orthodox believers of the Kyiv Patriarchate, and Protestants.

Experts agree that Russia’s plan to seize Crimea existed for a long time, same as its plan to capture Ukraine. It was only a question of when. At first, Putin acted constitutionally, intending to control Ukraine through Yanukovych. When the Maidan won in Kyiv and Yanukovych fled and created a power vacuum, Russian leadership decided that it was a convenient moment to implement the first part of their plan. There were also hints about the second part of the plan at that time: both the Speaker of the Crimean Parliament Volodymyr Konstantinov and the “Prime Minister” of Crimea Serhii Aksionov said that after Crimea, all of Ukraine should join Russia.

Photo: Unian.

“Why didn’t you react in 2014, and now, eight years later, you are reacting so strongly?” an Italian journalist asked me in the first days of the full-scale war. I responded: “First of all, at that time it was a shock for Ukraine – few believed that Russia would invade. Secondly, our army was not ready for war. We have since understood that war is possible, and the army has become much stronger.” And thirdly, over the years, it has also become more visible – both to the world and to us – what Russia is, and what Ukraine is.